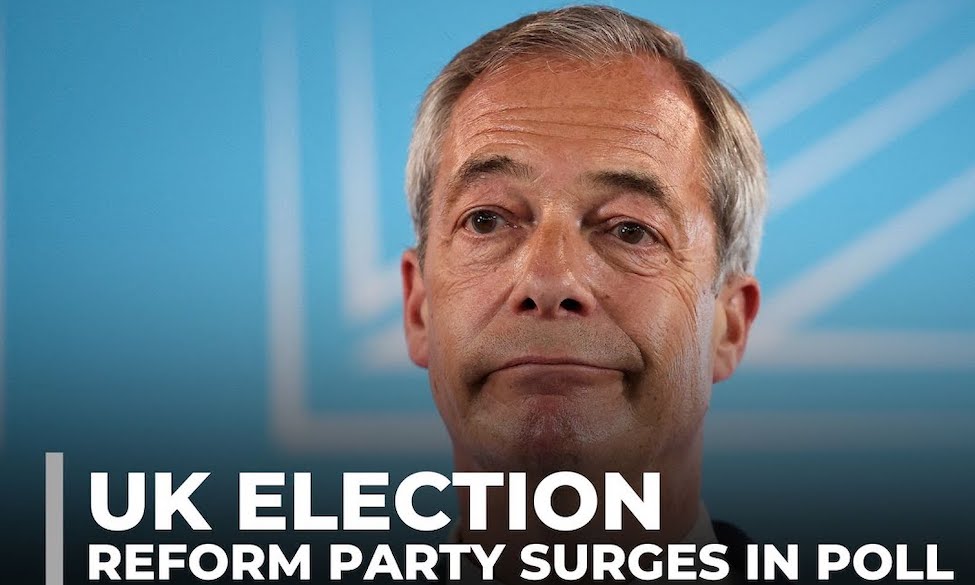

The Reform party is currently heading opinion polls, with 28 percent of people indicating their intention to vote for it at the next general election.

Of course, the next general election is not expected until 2029, and opinion polls are designed not so much to gauge opinions as to form them. It could also be argued that Reform’s ‘lead’ in the polls has been manufactured alongside the fomenting of anti-immigrant sentiment to stoke division within the working class.

That said, the party’s rise from its small beginnings as a party of resistance against the bureaucracy of the European Union to a potential party of government has been striking. Given the parlous state of the ruling class’s preferred parties of rule (the Conservatives and Labour, in that order of preference), however, it is not entirely surprising.

Reform’s ancestry goes all the way back to 1991, when a petty-bourgeois libertarian academic and lecturer in economics, Alan Sked, founded a cross-party grouping called the Anti-Federalist League. The grouping, which according to Sked held no position on immigration at the time of its formation because it was ‘not then seen as controversial’, was formed against the backdrop of the drafting of the Maastricht treaty – a treaty that established the European Union as the replacement for the old European Economic Community (EEC), a political entity that was built around three key pillars.

The first of these pillars would be the ‘European Communities’, around which economic, social and environmental policies would be set. The second was the establishment of common foreign and security policies, while the third was justice and home affairs. In summary, the Maastricht Treaty was the single most significant step towards the full federalisation of the imperialist trading bloc (now known as the European Union) since the founding of its ancestor, the European Coal and Steel Community, in 1952.

The Anti-Federalist League and Ukip

The Anti-Federalist League, holding an oppositional position to the federalisation of Europe and what it saw as Britain’s loss of independence within the European Economic Community, stood 17 candidates in the 1992 general election, but lost its deposits in all of them. With the signing of the Maastricht treaty by EEC member states, and with some Conservative MPs (known as the Maastricht rebels) mobilising in opposition to Britain signing this treaty, Sked and his associates in the league decided to transform their organisation into a bourgeois political party in its own right – the United Kingdom Independence party, or Ukip.

Ukip made no electoral breakthroughs in the period from 1992 to 1997. being overshadowed by another single-issue, anti-EU party in the form of the Referendum party. This organisation was led by Sir James Goldsmith, a millionaire businessman who, alongside other similarly wealthy individuals, bankrolled the party.

Nigel Farage stood as a Ukip candidate for election as an MP in the Wiltshire constituency of Salisbury in 1997, polling just 5.7 percent of the vote. This would be the second in a run of seven consecutive electoral defeats for Farage over a 30-year period that began in 1994.

Following this latest electoral disappointment, a faction of Ukip, led by Farage, held a meeting in Basingstoke, Hampshire to discuss the party’s poor electoral performance. They chose not to invite Sked, but they did invite media representatives. Sked claimed that the party, which had no media profile or name recognition, was able to field fewer than 200 candidates and had just £40,000 in the bank – an amount so modest that winning a single parliamentary seat would be difficult, let alone a general election.

In response to the convening of this meeting, Sked (or the party’s executive committee, exactly who is not clear and Sked’s own account is contradictory) expelled Farage and two other party members for “bringing the party into disrepute”, so beginning a long and expensive legal dispute that ended with the party relenting and restoring Farage and his co-conspirators to membership.

Sked himself left the party shortly afterwards. Accounts vary as to whether he resigned or was ousted in a Farage-led coup, but Sked said that he believed that the party that he had founded had become racist – a fair assessment given the number of contemporary members who have previously had associations with the racist British National party (BNP).

With its founder and leader gone, and with its 1997 election campaign a ruinous disaster, Ukip was handed a lifeline by the ruling class in 1999. The European Parliamentary Elections Act changed the electoral system for electing members to the European parliament (MEPs) from ‘first past the post’ (as used in British bourgeois parliamentary elections) to a ‘closed list’ system, whereby voters would vote for a party rather than a candidate.

Under this system, each party fields a list of candidates and those at the top are elected according to the proportion of the vote that they receive. This change meant that smaller parties like Ukip, but also Welsh nationalist party Plaid Cymru and the Green party were able to send MEPs to the European parliament – in some cases for the first time.

With the Referendum party wound up, Ukip became the main party of anti-EU protest votes – particularly in European elections, which suffered from notoriously low voter turnouts. The BBC took to inviting party representatives, principally Farage, to appear on the dreadful Question Time programme and its presenters were sure to steer every discussion point towards the political territory on which he felt most comfortable – immigration.

It should be noted that, despite the profile of the party being raised by the BBC and other sections of bourgeois media, this did not translate into domestic electoral success. In fact, the party only polled 3.1 percent of the popular vote in the 2010 general election.

2010 coalition and the demise of the Liberal Democrats

In 2010, the ruling class yet again gave Ukip a lifeline. The Liberal Democrats, a party that in the period leading up to the general election of that year had adopted policies which were arguably to the left of the Labour party, leapt into bed with the Conservatives and formed a coalition which was subsequently to prove completely disastrous for them.

The ConDem coalition government, in which the Liberal Democrats were junior partners, pushed through deeply unpopular policies, including the tripling of university fees and rampant austerity – an economic attack from which the working class is still reeling. As a result of its assistance in launching this class war, the LibDem party suffered reputational and electoral damage from which it still has not recovered.

With the option of the Liberal Democrats as an outlet for disgruntled protest votes gone, Ukip positioned itself as a party of protest for those who might otherwise abstain altogether. Capitalising on voter disgruntlement at swingeing cuts imposed by the government, and on the general societal malaise which accompanied this austerity programme, Ukip was able to gain a degree of electoral success in local elections in both 2012 and 2014 (when it won 163 council seats), and then in the 2015 general election.

The political presence of Ukip in this period not only corralled voters towards the notion that Britain’s ills could be solved by leaving the European Union, but re-opened fissures within the Conservative party, which has always been deeply split on the subject of the European Union.

The Conservatives won the 2015 election with an outright majority of 12 seats as the Liberal Democrats were almost completely wiped out – slumping from 57 seats to just eight. Labour’s long-standing support in Scotland also completely collapsed – partly because of its position on Scottish independence, but also because the party’s policies were almost indistinguishable from those imposed by the coalition for the previous five years. The phrase ‘Red Tories’ was first coined in Scotland.

Ukip actually gained a larger percentage of the popular vote than the Liberal Democrats in 2015, polling 12.6 percent of the vote, yet the vagaries of the British electoral system meant that its sizeable popular vote share resulted in the return of just one member of parliament – in Clacton. This Essex constituency was represented by Douglas Carswell, who had defected from the Conservatives to Ukip in 2014.

Meanwhile, Farage ran for MP in the since-abolished Kent constituency of South Thanet, but was pipped to the post by Conservative Craig Mackinlay by just over 2,800 votes.

Cameron’s Conservative compromise

With a growing number of Tory MPs agitating for a referendum on Britain’s future membership of the EU, and with the threat of these MPs deserting the party for Ukip, then prime minister David Cameron was forced into including a pledge in the Conservatives’ 2015 election manifesto that his government would hold a plebiscite on Britain’s membership of the EU if re-elected.

Accordingly, a plebiscite took place on 23 June 2016 after a campaign that ran from 15 April. All the major political parties, including the Conservatives, Labour (then at the time by the previously Eurosceptic Jeremy Corbyn), the LibDems, the Scottish National party (SNP), the Greens and others, all served the interests of their ruling-class masters by rallying to the cause of remaining in the European Union. Meanwhile, Ukip campaigned vociferously in favour of leaving, although it opted not to join the ‘official’ Vote Leave campaign, instead affiliating itself with the Leave.EU grouping.

The referendum gave the working class in Britain a unique opportunity to kick the ruling class where it hurt. British workers had seen at first-hand the effects of over five years of relentless austerity imposed by the government, and had seen also the paltry policy offerings of the major parties in the 2015 general election, which was essentially to carry on doing exactly the same as the Tories, LibDems and Labour had already done in the previous seven years since the financial meltdown of 2008.

Workers, who had been told over and over again via the bourgeois media and by all political parties, that their deteriorating living standards were caused on the one hand by immigration (especially the free immigration from the EU) and on the other by European bureaucracy, were resistant to ruling-class blandishments in favour of remaining in the EU and ‘not rocking the boat’. They knew they were being pressured (blackmailed) into voting Remain and, angry with austerity, they used the referendum as a ‘screw you’.

On 23 June 2016, in a referendum in which over 33 million people participated, it was decided that Britain would leave the European Union. Not only was this a pivotal moment for the British ruling class, it was also a pivotal moment for Ukip.

Nigel Farage, who had led the party since 2010 (having also led it for a previous stint from 2006-09) resigned his position and left the party, which then went into a period of decline. Arguably, its whole point of existence had been rendered moot by the decision to leave the EU, and its membership has since dwindled to just 3,000. As when it was a major political force in Britain, far-right elements continue to be active in its ranks.

However, this was not to be the end for Farage.

Farage’s next political vehicle: the Brexit party

The Brexit vote of 2016 sent shockwaves through the ruling class. Not only had the elites underestimated the levels of anger amongst British workers and their willingness to act upon it, they clearly had no idea how to deal with this huge blow that the working class had landed on them.

The political class went into a tailspin. David Lammy, the foul and contemptible Labour MP for Tottenham and now secretary of state for foreign and commonwealth affairs, called for Parliament to ignore the referendum, while prime minister David Cameron resigned immediately following the vote, standing down as an MP within three months.

There followed a prolonged period of prevarication on the part of a deeply divided ruling class, whose parliamentary representatives effectively split themselves into three camps: those who wanted a ‘hard’ Brexit (whereby Britain would exit the European Union on World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules), those who wanted to see Britain leave the EU but with a negotiated exit agreement that maintained many aspects of full EU membership, and those who didn’t want Britain to leave the EU at all.

By 2018, two years after the Brexit referendum, nothing suggested that the ruling class had either the inclination or the nous to deliver Brexit, and the electorate was becoming increasingly exasperated. What had at first appeared to the casual observer to be the ruling class making a careful, deliberate and cautious exit from the European Union had, after two years, started to look like blatant stalling and prevarication.

Jeremy Corbyn and the Labour party that he led was a key player in this stalling and prevarication. Farage, who was firmly in the camp of the hard Brexiteers, decided to show his hand.

He backed the ‘Leave Means Leave’ campaign, which was co-founded in 2016 following the Brexit referendum by property magnate Richard Tice. Farage was later to become the campaign’s vice-chair, and it was this association between Farage and Tice which was to lead to the foundation of the Brexit party in 2018.

‘Leave Means Leave’ held the position that any negotiations with the European Union on Britain’s exit must include a ‘no-deal’ Brexit as a fall-back position. Essentially, Britain should be able to fall out of the EU and default to WTO terms of trade if a settlement could not be reached through negotiation in a suitable timeframe.

To many in the ruling class, this position would be completely unacceptable: they expected and demanded frictionless movement of money, goods, services and, most importantly, people between Britain and the EU (and vice versa), and they simply could not countenance that frictionless movement ending.

However, capitalists like Farage and Tice always held the view that the EU acts as a bureaucratic barrier to this frictionless movement and asserted that leaving the union at any cost was necessary not only for this movement to continue, but also to allow the British ruling class to continue its attacks on the living standards of the British working class without any perceived hindrance from the European Union.

Of course, the reality is that the European Union has never been at the vanguard of protecting workers’ rights and only the most foolish trade union apparatchik could believe that it was. Weak and easily circumvented pieces of legislation like the ‘Working Time Directive’ have done almost nothing to protect workers from the predations of employers and, frankly, they were never intended to.

These laws are part of the costume in which the European Union has chosen to dress itself since the defeat of the working class in Britain in the mid-1980s: as a guarantor of workers’ rights against hostile national governments. And the British trade union movement fell for it hook, line and sinker.

Farage resigned from Ukip after 25 years’ membership in late 2018., and he let it be known that he was concerned with the Gerard Batten’s leadership of the party after he appointed far-right activist Stephen Yaxley-Lennon (better known as Tommy Robinson) as an adviser. Farage also complained that Batten was “obsessed with the issue of Islam” and stated that he didn’t believe that Ukip was founded to fight a “religious crusade”.

Clearly, Farage understood that in order to be of greatest service to the ruling class, he needed swiftly and decisively to distance himself from unsavoury elements like Tommy Robinson, whose viciously racist politics are not acceptable to the vast majority of British people.

While it may well be true that Ukip was not founded as an anti-islamic project, its populist leanings and the ruling class’s deeply islamophobic rhetoric and policies (which have their roots in Tony Blair’s government and the middle-eastern wars that were launched after the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Centre in New York in 2001) have led Ukip to attract all sorts of far-right elements, some of whom came to the party as refugees from the shipwrecked British National party, which hit the proverbial rocks with the demise of Nick Griffin’s leadership in 2014.

Early 2019 saw Farage pushing his pro-Brexit agenda even more forcefully. The Brexit party, which was in fact a private limited company co-owned by Tice and Farage (with the latter owning the majority of the shares), announced its inauguration in January. Later the same year, Farage, as part of the ‘Leave Means Leave’ campaign, began the ‘March to Leave’ – starting in Sunderland on 16 March and scheduled to end with a rally in London’s Parliament Square on 29 March – the date that had been set for Britain to leave the European Union, but which was missed by a combination of conflicting ruling class interests and blithering incompetence.

The march may not have made the same impact as that which took place the previous week, when hundreds of thousands of pro-Remain campaigners marched on London calling for the democratically-determined decision of the working class be set aside in favour of more pressing concerns, like the ease of getting through passport control when on holiday or sending one’s offspring to Spain for work experience.

It was clear that the unresolved question of Britain’s EU membership (and the political establishment’s response to the voters having given the ‘wrong’ answer) still exercised a sizeable section of the electorate, creating a wave of discontent that Nigel Farage was intent on riding.

The Brexit party’s chief (arguably only) policy aim was for Britain to leave the European Union on WTO terms. Farage himself stated that there was no material difference in terms of policy between the Ukip party he had recently left and the Brexit party he was an integral part of founding, but that “in terms of personnel, there’s a vast difference” – implying that the Brexit party was very much like Ukip, but with the meddlesome far-right influences ‘removed’.

Farage and the Brexit party’s profiles were systematically elevated in the bourgeois media. Videos of his acerbic speeches to the European parliament were regularly uploaded to YouTube, while he added to his 33 previous appearances on BBC’s Question Time by making two more in 2019. This was on top of the countless appearances he made in interviews and discussions across the spectrum of bourgeois media.

It was clear that Farage was performing a vital service for the ruling class, which was to push for Britain’s exit from the EU to cause as little harm to their interests as possible, and to act as countervailing force to the continuing, though clearly foundering, attempts by Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour party to somehow deliver a ‘workers’ Brexit’.

Later in 2019 the Labour party, at its annual conference in Liverpool, voted to support a policy that committed a Labour government to putting any Brexit deal to the electorate, including an option to remain in the EU (ie, a second referendum). This complete reversal on the Brexit position contained in Labour’s 2017 general election manifesto was backed by sizeable sections of the trade union bureaucracy and was carried through with barely a whimper of resistance from Corbyn or his acolytes, and it effectively doomed Labour as an electoral force in the 2019 general election.

Meanwhile, the Brexit party took the decision not to stand candidates in 317 parliamentary seats in 2019. This ensured that the Conservatives, who had a clear ‘get Brexit done’ policy under leader Boris Johnson, had a clear run at office without the risk of the Brexit party splitting the pro-leave vote.

In fact, the Brexit party need not have concerned itself – the Labour party had done much of the electoral heavy lifting with its suicidal policy on a second referendum. The Tories cruised to victory, garnering an 80-seat majority and condemning Labour to its worst haul of parliamentary seats since 1935. Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour party was, deservedly, in tatters.

From Brexit to Reform

Following the 2019 general election the Brexit party announced its intention to rebrand itself as the ‘Reform party’ once Britain had left the European Union. Its MEPs continued to make mischief in the halls of European power, including former MP and right-wing firebrand Ann Widdecombe, who was expelled from the Conservatives after she stood, and won, as a candidate for the Brexit party in the European elections in 2019.

Widdecombe, who had built a reputation amongst the Tory right wing for her deeply conservative and religious views on topics like IVF, gay marriage and the age of consent, claimed that the established parties “needed a seismic shock” after their failure to deliver Brexit in a timely manner.

Farage decided to stand down as leader of the Brexit party in 2021, and Richard Tice took over. The party continued to poll modestly in elections, including for the Welsh senedd, Scottish parliament and European parliament. Despite its success as a buttress for the Conservatives’ ‘Get Brexit Done’ strategy in 2019, it had failed to make any electoral breakthrough of its own, notwithstanding the MEPs it had sent to Brussels.

However, the decline and fall of the Tories in the period from 2020 to 2024 offered Reform the opportunity to position itself as a ‘serious’ right-wing party and a viable alternative to the ruling class’s preferred party of government.

2020-25: The fall of the Tories and the rise of Reform

The Tories’ grip on power, which had seemed vice-like just months previously, began to loosen in the period from early 2020 until the July 2024 general election.

The government’s response to the Covid pandemic, as well as the fast-and-loose interpretation of lockdown rules adopted by government advisors, ministers and indeed the prime minister himself, led to the final downfall of Boris Johnson, and the 50-day term of office of his replacement, Liz Truss, was followed by the coronation of Rishi Sunak as prime minister just weeks after his own MPs had rejected him.

During this time, the Tories had slid from an apparently unassailable position to one of complete untenability. In May 2024, Rishi Sunak stood outside 10 Downing Street in the pouring rain to announce that he would be calling a general election for 4 July. It was clear that Sunak was hitting the electoral ‘eject’ button before the plane he was piloting crashed.

Inflation, previously rampant, had dropped to 2.3 percent (officially) and interest rates were down at 5.25 percent, good news that would mean that while the Tories would most probably lose and lose heavily, they would lose heavily on as near to their own terms as possible in the circumstances.

Reform, once again heavily promoted by bourgeois media in the period leading up to the election, was being deployed not as a potential party of government but as a means by which the voter base of the Tories could be split, securing their downfall – a strategy that was devastatingly successful.

Labour was returned to office for the first time since 2010, garnering just 34 percent (less than 10 million) of the popular vote in an election with a voter turnout of less than 60 percent. Yet despite this weak vote and poor turnout, Labour romped home with 415 seats – just three fewer than the 418 it gained in 1997, but with four million fewer votes!

The margin of Labour’s victory can be broadly explained as being due to Reform taking millions of votes from the Tories in hundreds of seats, splitting the right-wing vote and allowing Labour to take victory with fairly modest majorities in an election where the turnout was extremely low.

It was clear to many observers that Labour’s majority was ‘a mile wide, but an inch deep’. Labour’s sizeable parliamentary majority did not suggest that the party enjoyed any sort of popular mandate.

This made itself obvious in the weeks following Labour’s election. MPs voted to cut the Winter Fuel Payment, an allowance given to pensioners to assist them in paying their exorbitant energy costs in the winter months thanks to the price-gouging of the robber barons who own the privatised energy sector.

This abolition was met with outrage from the trade union movement, pensioners advocacy groups and charities. Months later, Labour made a U-turn of sorts, but the damage from pushing through this measure in the first place remained.

Labour also made itself deeply unpopular with farmers by abolishing the exemption on inheritance tax for land and property that farmers have benefitted from since 1984. This change meant that the children of farmers would in all likelihood be liable for inheritance tax on their farms when their parents died. Given that farmers who own their land are often asset rich but cash poor, this would mean that many would be forced to sell land to pay any tax bill.

With Monsanto and Dyson Farming among others eager to expand their agricultural landed estates, the case that this change in the law was a de facto method of transferring land ownership from the hands of individual farmers to huge corporations has merit.

All of this, along with policies continued from the previous government, including the transfer of billions of pounds to fund the Nato-backed proxy war in Ukraine, the cost-of-living crisis that continues unabated, and the continued and carefully managed decline of public services, has left the Labour government in an untenable position within just twelve months of its election.

The working class see, as clearly now as ever, that change cannot be achieved through the ballot box. Public faith in one of the bourgeoisie’s key pillars of ‘civilised society’, parliamentary democracy, is at an all-time low.

In order to restore at least some viability for bourgeois parliamentarism, the ruling class has been deploying a two-pronged strategy. It is using its organs of state propaganda to push the narrative that the nation is being flooded by a tidal wave of ‘illegal’ migration, while at the same time promoting Reform as its antidote.

In fact, the ruling class has always needed a readily available layer of hyperexploitable (preferably deportable) labour and has never cared a jot where that labour comes from. Governments have consistently placed immigrant workers in poor working-class areas whose public services, jobs and housing have already been cut to the bone, and then sought to blame said immigrants for the cuts that they, on behalf of the ruling class, have inflicted.

Reform’s leaders, like the Tories before them and like the Labour party today, use immigration as a weapon to divide the working class.

Farage demonstrates his suitability for bourgeois power

The keys to political power in this country are, as they have been for hundreds of years, held by the ruling class. Reform, which is positioning itself as the ‘anti-establishment’ alternative, will not be allowed near power unless it can meet the ruling class’s strict criteria.

To that end its leaders have undergone a series of tests to gauge their suitability for bourgeois office, and their actions are instructive for workers who are looking at Reform as a prospective party of rule.

Sir Rupert Lowe, elected as a Reform MP for Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, was unceremoniously booted out of the party for making the mistake of believing that Reform was really about ‘stopping the boats’ and deporting ‘illegal’ immigrants en masse – as its spokespeople have repeatedly proclaimed. This was not, in fact, Reform’s policy, and it never will be if it genuinely hopes to achieve bourgeois office.

While Reform’s policies on immigration included banning people on student visas from bringing their partners or children, charging employers 20 percent national insurance for foreign workers (instead of the going rate of 13.8 percent) and sending ‘illegal’ migrants crossing the Channel on boats ‘back to France’ (exactly how has not been explained), Reform acknowledged that the National Health Service (NHS) requires migrant workers to function, hence these workers being considered ‘essential’, and has therefore exempted them from its proposed draconian anti-immigration policies.

As we have written previously, the ruling class needs a constant and uninterrupted supply of labour. Reform’s 2024 general election manifesto, with all its equivocation on immigration, reflects this need.

Reform leader Nigel Farage has also done a very noticeable reverse ferret on Ukraine. In September 2014 he made a speech in the European parliament criticising his fellow parliamentarians and posturing as an antiwar, anti-establishment figure. He framed the European Union as an empire with territorial claims on Ukraine that was provoking Russian president Vladimir Putin into a military response to Nato’s baiting.

As recently as 2024, Farage reiterated his stance on Ukraine and the provocation that had led Russia to launch its special military operation. Speaking to the BBC, he stated that the “ever-eastward expansion of Nato and the European Union” since the fall of the Berlin wall had led to the Russian military action in Ukraine.

The bourgeois media were openly hostile towards Farage for taking this stance. Now, however, his position on Ukraine is almost indistinguishable from Sir Keir Starmer’s – or, indeed, form that of the rest of the imperialist political class.

In February 2025, US president Donald Trump characterised Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky as a “dictator”. Zelensky has indefinitely postponed the Ukrainian presidential election (which was due in May 2024), declared martial law, banned trade unions hostile to his regime, heavily restricted the national media and repressed opposition parties. Given these facts, Trump’s characterisation of Zelensky appears perfectly fair.

Yet Farage took to media outlets to counter this characterisation, asserting that Trump’s assessment of Zelensky “should not be taken literally”. Farage was even criticised prominent Reform supporter Tim Montgomerie for not distancing himself from Trump’s comments sooner. The next month, Farage distanced himself from Donald Trump’s approach to securing a ceasefire in Ukraine, claiming that the president was conceding too much territory to Russia and would position President Putin as a “victor” in any settlement.

Farage and Reform know very well that, to attain office, they must show themselves to be trustworthy custodians of British imperialism – which means pledging to continue the seemingly endless slaughter in Ukraine in order to further the British ruling class’s aim of weakening (and ultimately destroying) Russia as an independent and sovereign state.

Then Farage, who just a few months earlier was criticising Sir Keir Starmer for his inability to define a woman, said that a Reform government would permit men to enter women’s prisons following a risk assessment:

“When it comes to trans women in prisons, isn’t it interesting that we run our country with people who become ministers who generally have no idea of the subject matter that they’re talking about.

“I’ve personally never worked in a prison so I can’t answer it but I think you’ll find the answer you get from somebody who has worked in prisons at the highest possible level is basically it’s about risk assessment.”

Farage’s assertion that because he hadn’t worked in a prison, he could not say whether biological men should be jailed in the female prison estate was somewhat curious, especially when set against the criticisms he aimed at Keir Starmer just months earlier.

Farage’s position was buttressed by his newly-appointed ‘prison tsar’, Vanessa Frake, who said: “There are equally vile women as there possibly are trans women. So it’s all about the risk assessments for me, and each has to be done on an individual basis.”

Farage subsequently “clarified” (backtracked on) his position, claiming that he had never supported men in women’s prisons. However it is hard to believe that Mr Farage, who usually very self-assured in conveying his political positions of a raft of topics, including on gender ideology and its pernicious consequences for women, could have made such a gaffe unless he had been explicitly briefed by his advisors to equivocate in the manner that he did.

Despite their protestations to the contrary, the Tories during their 15 years of bourgeois rule proliferated the spread of identity politics in all areas of the state, including the media, academia, the judiciary, the police and even the apparatus of the political class itself.

Gender ideology, like all identity politics, is bourgeois ideology designed to divide and atomise the working class. Reform will be expected to adhere to its tenets, or at least turn a blind eye to them, if it wants to be handed the keys to office by the ruling class.

Preparing the ground for election 2029

It is highly likely that, notwithstanding a meteoric rise in the fortunes of the Labour party between now and the next general election, Reform will be manoeuvred by the ruling class into a position either to form a government (albeit potentially a coalition one) or at least to form some sort of an electoral pact with the Tories.

With the full support of the British media, Reform’s leaders have gone to great lengths to create an image of anti-establishmentarianism, a ‘third way’ in political terms, and these efforts may bear electoral fruit.

But the case needs to be made to the working class that Reform is just another version of the same old story of which we are becoming so tired. In their efforts to maintain the facade of bourgeois democracy, the ruling class presents many shop fronts to the workers: Conservative, Labour, LibDem, Green … and now Reform.

Reform may be the shopfront of choice for the working class and wider electorate at this moment in time, but as the party’s actions in the last few months have demonstrated, it is every bit as much a ruling-class party as its more established counterparts. Bourgeois democracy in a decaying imperialist nation offers no prospect of change – the workers will only ever attain true liberation when they win it for themselves.

Meanwhile, we must not react to the rise of Reform with excessive fear. It is the bad habit, cultivated over 120 years, of so many working-class Britons voting for the imperialist Labour party that has been the real vehicle for tying British workers hand and foot to imperialism.

At present, the most important point for workers, socialists, communists and progressives to push is the necessity of breaking all links between the organised working-class movement and the Labour party.

This does not imply support for either Tory or Reform, any more than for LibDems, Greens, Plaid Cymru, the BNP or the Scottish National party. It simply means that once the workers have kicked the habit of Labour party social democracy, with the entire firmament of bourgeois politics in chaos and disarray, the opportunities for them to organise around a really revolutionary party and policies reflecting their own material interests will be far greater.

It is clear that, as the crisis of capitalism accelerates and the imperialists lose their grip on their colonial possessions, what is needed above all else is communist leadership. We are as yet a good distance from achieving this, but we can say with chairman Mao: “Everything under heaven is in utter chaos: the situation is excellent.”