The following speech was delivered at our recent meeting to commemorate the 108th anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution, held in Southall, west London on 8 November 2025.

*****

During World War 2, women across the allied nations fought valiantly against fascism. In all countries, women’s labour was essential to sustaining the war economy – producing munitions, food, uniforms and medical supplies. Women entered the workforce in unprecedented numbers to replace men who had been sent to the front. Factories, transport, agriculture and communications often became female dominated.

But similarities in contribution to the fight against fascism between women in the west and their socialist sisters ends there – because the way they fought fascism, the way they understood their fight, differed greatly.

It wasn’t that women in the west were less courageous, or less willing to resist fascism. Far from it. But something deeper was at work – consciousness.

We are constantly told that humans are basically selfish, greedy, cruel and out for themselves – that this is simply ‘human nature’. That outlook has never sat easy with me, but I couldn’t articulate why until I read Karl Marx. And suddenly it all made sense.

“It is not the consciousness of men that determines their being,” he wrote, “but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness.” (Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, 1859)

In other words: morality isn’t fixed. It isn’t inherent or eternal. It grows out of the conditions of life – from our class structure and the mode of production. And that’s why, when fascism threatened the world, women in the Soviet Union, in China, in Korea, and wherever communist partisans fought, responded differently from their sisters in the west. Not because they were born different – but because they lived differently.

Socialist women of a new type

And this was most true for Soviet women, whose consciousness had been transformed by socialism itself. As such, the Nazis weren’t just fighting an army – they were fighting the united consciousness of the Soviet people. A people whose wealth was shared, whose labour built their future, and whose unity had been tempered by two decades of socialist construction.

This is perfectly exemplified in a letter sent by women working at a Moscow brake factory to Soviet army men in the summer of 1941:

“Go into battle against the enemy boldly, defend our land, our children, our freedom. You are leaving for the front; we are staying behind in the rear. But there is no difference between the front and the rear in our country.

“We will give all our strength, all our energy to replace you in industry, to supply you with everything you need. If necessary, we will work day and night; if necessary, we will help you, arms in hand.

“Don’t worry about us, don’t be anxious – we are wholly conscious of our duty to our country, we fully understand the difficulty and the seriousness of the situation.”

Soviet women were the only women officially admitted to frontline combat – as pilots, tank drivers, machine-gunners and snipers. The large number of Soviet women who took part in partisan warfare was an unexampled manifestation of their patriotism.

But then, Soviet women were no strangers to struggle. After a century of sacrifice, of revolution and civil war, they were seasoned fighters – battle-hardened not only in war, but in the long, bitter fight for communism itself.

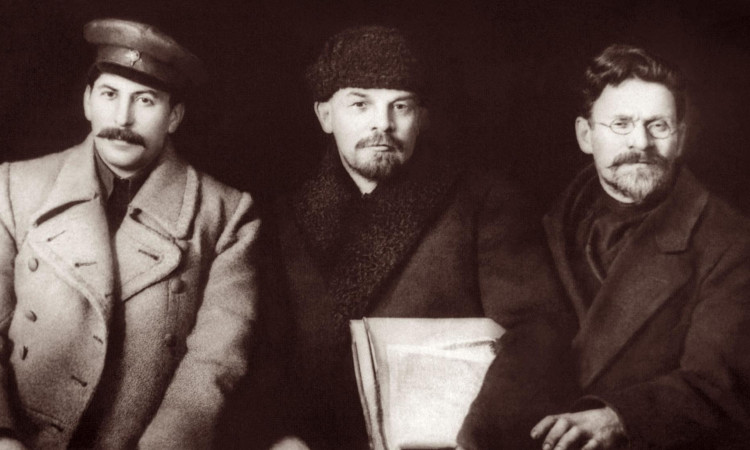

In Clara Zetkin‘s Reminiscences of Lenin she refers to a discussion with him on the woman’s question where he captured this spirit by saying:

“How brave they were. How brave they still are! Just imagine all the sufferings and privations that they bear. And they hold out because they want to establish the Soviets – because they want freedom; communism.” (1924)

Lenin, like Marx before him, understood that there can be no true democracy – no complete human freedom – without women taking their rightful, permanent place in the political life of the country and in the public life of the community.

Under socialism, Soviet womanhood had earned a dignity and a status unknown anywhere else on earth. Hewlett Johnson, the so-called ‘Red Dean of Canterbury’ once wrote: “No world was darker for women than that which existed under the Russian Empire – and none more bright than that which dawned with the Soviet Union.” (The Socialist Sixth of the World, 1939)

In 1936, true democracy was enshrined in law when the Soviet constitution declared: “Women in the USSR are accorded equal rights with men in all fields of economic, state, cultural, social and political life.”

Even now, when I read those words, I feel a shiver. Imagine it – equality, not as a vacuous promise, but written into the very fabric of society. Women were not just equal in law; they were equal in fact.

A new generation had grown up under Soviet power – a generation that knew itself as the collective owner of one-sixth of the earth’s surface, and that knowledge gave it strength beyond measure. In the Soviet Union, there was no division between soldier and civilian, old and young, man or woman. The population stood as one. The entire nation became a single, living front.

And here, the emancipation of women proved its worth. Decades of socialist equality had not only transformed lives – it had prepared women for leadership, for labour, and for war.

Soviet women in the Great Patriotic War

By 1940, a year before the Nazi invasion, Soviet women were tractor drivers, engineers, doctors, scientists, party organisers and locomotive drivers – four 4,000 drivers in fact, when nowhere else in the world had even one. They tempered steel, forged iron and handled the most complex machinery.

Before the war, women made up 45 percent of all industrial workers; by the end of 1942, over half. They built Moscow’s fortifications, repaired railways under bombardment, and sustained collective farms, some of which produced four times their usual yield.

When the armaments factories moved ‘bolt by bolt’ to the east, it was women who reassembled them. They worked until they dropped from exhaustion – not for private profit, but out of faith in victory and duty to the collective. Without their selfless devotion, the defeat of fascism would not have been possible.

And they fought – in the infantry, as partisans, and in the skies.

Among them, the famed 588th Night Bomber regiment. The fascists called them ‘Night Witches’ because their near-silent gliding attacks in the dead of night made the sound of broomsticks sweeping through the air – a sound that filled German soldiers with dread. Their comrades affectionately called them ‘Little Sisters.’

Flying small, slow biplanes – crop-dusters really – these amazing women (girls, as they were mostly aged in their late teens and early twenties) carried out relentless night raids aimed at destroying supply depots, disrupting troop movements and keeping the fascists in a state of constant fear and exhaustion. They also flew behind enemy lines to supply partisans.

Their open cockpits offered no protection from bullets or the freezing wind; they flew without radios, armed with little more than pistols. With no bomb bay, they balanced bombs on their knees and dropped them by hand. Each night they flew up to ten missions, cutting their engines before releasing their bombs so they fell in ghostly silence.

So feared were they that the Germans promised an Iron Cross to anyone who could shoot one down.

Nearly a million women mastered every specialist role in the ranks of the Red Army during the war, not counting partisans or police. Ninety-five were awarded the title Heroine of the Soviet Union, the USSR’s highest title for valour. They were the first large group of women in world history to be officially recognised as national heroes for direct combat and military leadership.

In May 1943, the army set up the Central Women’s Sniper Training school – over 2,000 women graduated, just 500 survived. Legendary amongst them was Lyudmila Pavlichenko who became one of the deadliest snipers in history, credited with 309 confirmed kills. Her success challenged gender stereotypes and showcased women’s potential in warfare.

There were countless acts of heroism – like snipers Natalya Kovshova and Mariya Polivanova, who fought to the last bullet, then detonated their grenades when German forces overran their trench, sacrificing themselves to take the enemy with them. Both were posthumously named Heroes of the Soviet Union. Together, they had eliminated over 300 fascist soldiers.

In them all, and in millions like them, socialism revealed its truth: it had made women the equals of men – comrades, warriors, builders of a new world, and fierce defenders of their socialist nation.

Women on the east Asian front

Across Asia, too, women played a decisive role – particularly in China and Korea, where the antifascist struggle was inseparable from the anti-imperialist revolution.

Chinese women fought to expel the Japanese fascist invaders, defeat their own ruling oppressors and overthrow feudalism itself. They joined the Eighth Route Army and the New Fourth Army, serving as fighters, medics and political officers.

Communist-led resistance transformed women’s status, integrating them into every aspect of production and defence. Women’s participation was not symbolic, but essential to both the immediate war effort and the revolutionary restructuring of society.

American Marxist and journalist Agnes Smedley, who reported from China between 1937-45, contrasted women’s lives in the communist base areas with the old patriarchal order that still dominated much of China.

When she wrote, it was clear that a new force was being born. The women were discovering themselves. They were no longer shut away within the four walls of the house. They were taking their place beside the men – in the fields, in the workshops, in the army, and in the councils of the people.

Millions of peasant women joined the guerrilla bases, forming cooperatives and militia units that produced food, uniforms and intelligence for the front. Their heroism did not end with victory over fascism, for the revolution of 1949 would soon proclaim, in Mao’s words, that “Women hold up half the sky.”

In Korea too, when Marxist-Leninist Kim Il Sung mobilised women to be full participants in the fight for the revolutionary cause, he recognised that without women fighting as guerrillas in the Korean People’s Revolutionary Army, the revolution was deprived of half its strength. Theirs was not only a struggle against fascism, but against the most brutal form of imperial rule – colonialism.

In all of these movements, women were not there to ‘help the men’. They were the men’s equals – commanders, agitators and combatants whose courage inspired all around them.

So what do we learn from all this?

We learn that courage alone does not determine the future – consciousness does. Women everywhere were courageous, but courage under capitalism is channelled into the defence of property and privilege. Courage under socialism becomes a weapon for human liberation.

Where the capitalist woman was told that her place was in the home, the socialist woman was told that her place was in history.

Where the capitalist woman’s work ended when peace returned, the socialist woman’s work began – in reconstruction, in leadership, in the permanent transformation of society.

The capitalist world asked women to fight fascism only to restore the old order; the socialist world asked women to fight fascism to create a new one.

That is the real difference.

When we honour the women who fought fascism, let us remember them truthfully. Let us remember the Soviet pilots who flew through flak in open cockpits; the Chinese guerrillas who faced torture rather than surrender; the Korean revolutionaries who marched barefoot through the snow.

Let us remember, too, the millions of women in Britain and America who laboured selflessly, believing they were building a better world – only to find that the old inequalities returned as soon as the victory parades ended.

And let us draw the conclusion that Marx, Lenin and every revolutionary woman since has drawn: that the full liberation of women cannot exist without the liberation of society itself.

For in every age, in every land, women’s fight for equality has been bound to the fight against exploitation – the fight for socialism.

And so long as that fight continues, the example of the women who defeated fascism – the workers, the partisans, the pilots and the snipers – will light our way forward.

They proved that socialism makes women free – and that when women are free, humanity itself can triumph.

——————————

Additional background reading and resources

- Nina Popova, Women in the Land of Socialism (1949)

- Agnes Smedley, Battle Hymn of China (1944) and Portraits of Chinese Women in Revolution (1976)

- Ed Ella Rule, Marxism and the Emancipation of Women (2000)

- Anna Louise Strong, The Soviets Expected It (1942)

- Edited by Graham Lyons, The Russian Version of the Second World War (1976)

- CPGB-ML, The Soviet Victory Over Fascism (2006)

- Georgi Dimitroff, The United Front (1938)

- VI Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916)