Poor old Theresa May. She has been in many ways a perfect bourgeois career politician. From her schoolgirl dreams of following in the footsteps of Mrs Thatcher, she worked her way solidly up through the ranks of the Tory party. She had no skeletons in her closet, and has shown herself to be perfectly willing to say or do whatever her masters require, while holding no discernible opinions of her own.

May’s willingness to present black as white and dictatorship as democracy have been exemplary. She has proved her ability to implement the most brutal anti-worker legislation without a qualm and then to talk of the need to protect the little guy; been perfectly happy to facilitate jihadis via her post as home secretary and then to talk of the need to stand up to terrorism.

Above all, she has been willing to campaign first against and then for Brexit, as her masters and career prospects demanded. Having survived the chaos of the EU referendum and found herself unexpectedly in pole position as the last woman standing after the 2016 leadership contest, she appeared to have risen to the premiership by dint of keeping her head down while demonstrating whole-hearted loyalty to the ruling class.

Since becoming prime minister, however, May has discovered what the next incumbent will also find; what many of her equivalents in Europe are presently finding; and what, in fact, any leader of a bourgeois democratic state in the grips of a world capitalist economic crisis is bound to find: that chaos, disunity and the conflicting demands of her masters in the ruling class make the job she has been given the most poisoned of golden chalices … and now it looks as if the only Mrs Thatcher moment she’s likely to get is the one where, beaten and rejected, she finds that her services are no longer required by an ungrateful party and public.

May might be doing what she can to cling on for now, but she cannot avoid sensing that, without some minor miracle, her days are surely numbered.

Why was there an election at all?

Ms May’s position inside the party had been getting gradually weaker as attacks from within and without continued in the wake of the EU referendum. These mostly revolved around attitudes to Brexit, but included disunity over questions of war and austerity, and peaked in March when the prime minister was forced into a humiliating U-turn on her own budget, alienating her chancellor, Phillip Hammond, into the bargain. (Theresa May’s budget U-turn over national insurance hike prompts accusations of incompetence and recklessness by Joe Watts, Independent, 15 March 2017)

Faced with a non-stop barrage of criticism and sabotage from all those in parliament and the media who are set on scuppering the Brexit negotiations (including rebels within her own party), May wanted to increase her majority so as to have a surer base from which to outmanoeuvre her opponents and a stronger mandate with which to silence her detractors. She also wanted to be able to form a government that could see Brexit through and let the dust settle before having to call the next general election.

It would appear, too, that Mrs May had bought into the received Westminster wisdom that Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn was so unpopular and unelectable that the whole thing was bound to be a walkover; that she would triumph, much as in the Tory leadership contest, by doing nothing and allowing her opponent to shoot himself in the foot (or, rather, by leaving the media and his own party colleagues to destroy his electoral prospects on her behalf).

How did people vote?

It seems that voters went into this election with one major question on their minds: should Theresa May’s Tories be strengthened or weakened? This was the appeal May made to the public when she announced the election, specifically in relation to the Brexit negotiation, and that would appear to be the basis on which voters responded.

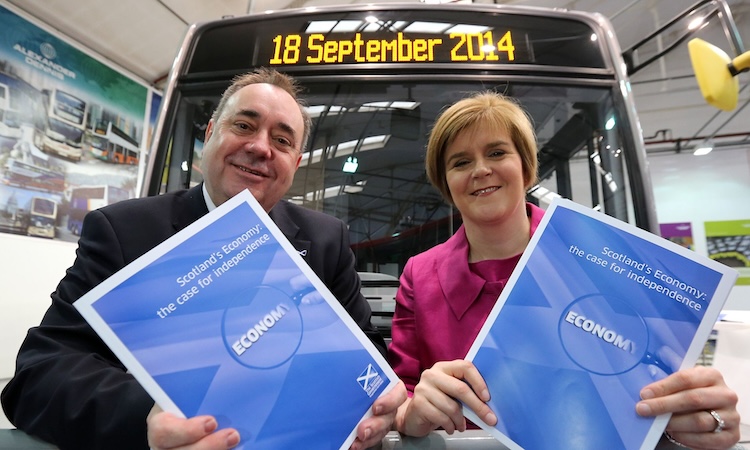

As far as the ruling class was concerned, this was most certainly the Brexit election (as, no doubt, the next one will be too). As far as working people were concerned, two major issues seem to have affected voting patterns in England and Wales: Brexit and austerity (including, most especially, the dismantling of the NHS, the housing crisis, unemployment, rising student debts and the general lack of prospects or opportunities for young people). In Scotland, added to these was the question of independence, and in the north of Ireland, added to these was the question of Irish reunification.

In general, it would seem that people voted in the way that they thought would be most likely to strengthen or weaken Mrs May’s government according to their views on the above. In view of the Tories having embraced the main points of Ukip’s former platform, Ukip itself collapsed, with its former voters split between Conservative and Labour, presumably depending on whether Brexit or austerity was their greatest concern.

Tactical voting was clearly and strongly in evidence; many constituencies became flat two-horse races. That is not to say that we have returned entirely to two-party politics as some are claiming; rather that voters appear to have focused their approach on a single question and then voted tactically in the way they thought might best achieve their desired outcome. So in England, for example, many people who wanted May out voted LibDem in seats where they felt that Labour could never get in and vice versa.

Not only Ukip’s vote collapsed but also that of the Green Party, which was derisory everywhere except in Caroline Lucas’s seat in Brighton, where no LibDem candidate stood and where the Green vote actually went up.

There are also indications (as yet unconfirmed by reliable figures) that a surge in turnout by previously disengaged younger voters may well have proven decisive in delivering not only the highest overall turnout in 20 years (69 percent), but also in swinging many seats from Tory to Labour. As a result, Labour gained 40 percent of both votes and seats (262).

In actual fact, it was not all bad news for the Tories as the results rolled in during the early hours of 9 June, for May’s stance on Brexit wiped out Ukip and gave the party gains in Wales, while the party’s stance against another independence referendum undermined the SNP and gained it seats in Scotland. But the governing party’s seat numbers collapsed catastrophically in England, particularly in university and anti-Brexit constituencies.

It is one of the many anti-democratic quirks of the British parliamentary first-past-the-post system that, despite increasing their share of the vote to the highest the party has received in decades (13.6 million votes, up from 11.3 million, equating to 42 percent of the vote, up from 37 percent), the Tories actually lost seats (318, down from 331). Of course, in another of the system’s quirks, the party’s 42 percent of votes was enough to give it 49 percent of the seats. (Election results 2017, BBC News, 9 June 2017)

So, without the triumphant landslide (in terms of seats) that she and her team went into the election predicting, May is seen to have gambled with what little majority the Tories had and to have very publicly lost her bet.

The battle of the manifestos

With her 20-point lead seemingly safe in her back pocket, Mrs May went into the election determined to put her stamp on the proceedings. Having surprised everyone in her own party (outside of a very small team of advisors) by calling the election in the first place, May went on to commit the cardinal sin of forgetting that while she in fact serves a tiny clique of the super-rich, in order to be elected she has to appear to be trying to serve the masses, and must be successful enough in this to persuade large numbers of working-class people to vote for her.

The hubris with which May included such anti-worker items in her manifesto as the ‘dementia tax’ and the scrapping of the triple lock on pensions defied belief, and had even her own supporters reeling in shock. These may well be aims of the ruling class, but what kind of politician believes they should actually be printed in a manifesto aimed at attracting working-class votes?

The need to backtrack on such insanely blatant attacks on her core voters (the better-off sections of older workers) did much damage to May’s attempts to project a ‘strong leader’ image – not only in the eyes of the electorate, but also within the ranks of her supporters. It also fatally undermined her mantra that only she could deliver ‘strong and stable leadership’ in these difficult times. Clearly, not only Mrs May but also the advisors who persuaded her that a re-run of the Iron Lady would prove popular in the battle to out-ukip Ukip are about to find themselves looking for employment elsewhere.

Meanwhile, Mr Corbyn’s manifesto included a whole list of eminently reasonable demands appealing to a wide cross-section of society. More funding for the NHS, a programme of council house building and the scrapping of student debt spoke to all those who are suffering under austerity, especially the young; renationalisation of the railways and other key utilities spoke not only to workers who are sick of being ripped off by the privateers but also to significant sections of the ruling class, whose ability to run their businesses is undermined by the inefficient and poor services that the private companies at present deliver.

Indeed, after decades of sucking out monopoly profits without renewing or even particularly maintaining the vital infrastructure for which the privateers are responsible, the only realistic way that these essential services are going to get back on track is through state intervention – the state being, in the final analysis, the executive committee of the capitalist class as a whole. After all, as several commentators have pointed out, not only in present-day imperialist Germany and France, but even in tsarist Russia the railways were nationalised!

And, of course, Corbyn’s promise to renew trident and to ‘press the button’ if need be allayed the worst fears of his detractors, while doing nothing to stunt the support of his former colleagues in CND and Stop the War.

How did May get it so wrong?

It is clear that Mrs May, along with the entire bourgeois media, failed to appreciate not only the attractiveness of Corbyn’s platform to large sections of the working class, especially to the young (and those who sympathise with the young: eg, parents, grandparents and teachers of teenagers and twentysomethings), but also to foresee that the liberal media’s hatred of Brexit might ultimately trump their hatred of Corbyn.

May was 20 points ahead in the polls while the media were united in singing the song of Corbyn’s ‘unelectability’. But, when push came to shove and it was too late for Labour to ditch Corbyn; when it was a choice between Theresa May’s declared intention of pushing Brexit through no matter what and the possibility of a coalition made up of members who are in the main opposed to Brexit (Jeremy himself notwithstanding), significant sections of the imperialist media and the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) were forced to wake up and smell the coffee.

Hence the sudden volte-face of the Corbyn-hating liberal ‘centre’; the abrupt turnaround by the likes of the Guardian, Independent, the BBC and even the Times, and the falling back into line of the PLP Blairites, who (presumably temporarily) stopped briefing against their leader and started extolling the virtues of his manifesto.

And so, at the last minute, Corbyn was transformed in a significant section of the media from a bumbling idiot whose subversive ideas would ruin the country if anyone was crazy enough to vote for him (which, of course, they wouldn’t be) into a likeable, down-to-earth chap who was in touch with the common folk and not afraid to stand up for what he believes. The liberal media stopped ignoring Corbyn’s triumphal progress and rapturous reception in cities around Britain and started to acknowledge the reasons for it, even going so far as hypocritically to join the chorus against May’s proposed new anti-terror legislation.

If the media had been in agreement that Corbyn must be defeated at all costs, Jeremy’s entirely rational responses to all the aspersions and slanders made against him would never have been reported, and the accusations would have been amplified. As it was, while the pro-Brexit press did indeed amplify every stupid slander, this only backfired when the responses were published and workers had a chance to decide for themselves.

Thus, for example, Mrs May’s attempt to use the terrorist attacks in Manchester and London to attack Corbyn for being a ‘terrorist sympathiser’ backfired when his mildly pointing out that British foreign policy was fostering terrorism was widely reported and workers had the chance to hear both sides of the case.

Crisis breeds chaos

To make sense of this election, the first thing that has to be understood is the context: the deep capitalist crisis of overproduction is creating conditions of chaos and uncertainty in all spheres of life.

As in all the other capitalist countries of the world, the ruling class is thoroughly divided over the best way to deal with the crisis, and this is reflected in the rancorous polarisation in the media and in the rancorous divisions within both the major parties, which are split over fundamental questions of Britain’s EU membership, of its wars abroad and subservience in these wars to US imperialism, and over the implementation of (if not the necessity for) austerity at home.

Moreover, the working class is increasingly frustrated and angry at the burden that the ruling class is trying to shift onto its back: the lack of decent jobs and housing, the privatisation and scrapping of public services, especially the health service; the rising cost of living alongside falling wages and conditions; rising unemployment and falling benefits.

The young, in particular, now face a situation where in order to get a job they must first acquire a crippling debt burden, and where living at home or becoming homeless seem to be the only options as far as housing is concerned. No sensible teacher would any longer dream of trying to tell an intelligent working-class teenager that if they work hard in school, they will undoubtedly do well in life. It is becoming crystal clear to all that the only way to do well as a young person today is to be born with parents who can afford to help you on your way to a decent job and a home of your own.

As the crisis deepens, there are vocal sections within every capitalist class in the world who declare that each country can find a way out of its troubles by protecting home markets and exporting more goods abroad. For the imperialists, we can also add to this list the aim of controlling more avenues of investment and sources of raw materials around the world. But one only has to think for a moment or two to see how futile this approach is when taken all together: clearly, if everyone’s home markets are glutted, there is not going to be much scope for increasing exports, and particularly not when everyone else is trying to do the same thing!

In truth, the ruling class has no answer to the crisis beyond austerity and the drive to war, and no answer to workers’ anger than to try to divert it against whatever scapegoats can be found from amongst the workers themselves – whether that be ‘benefit cheats’, single mothers, ‘foreign’ businesses or immigrants.

It is this need to promote scapegoats (in the form of immigration and the EU) that pushed the Tories into holding the Brexit referendum in the first place, and the success of decades of poisonous propaganda in convincing workers that their fellows are to blame for their problems that caused the ruling class to lose control of the outcome – all of which has contributed to the chaos we are witnessing now.

What has been the outcome of this election?

No stable majority government is possible with the present allocation of seats. A Tory/DUP coalition could create a majority government, but only just, and not one that any political commentator would consider to be practically workable. The quest for a ‘strong and stable’ government has led the Tories to become even more weak and unstable than they were before.

Moreover, the need to keep the protestant fundamentalists of the DUP on side at every turn could lead to serious consequences, not only within the Tories’ ranks, but also and more importantly in the north of Ireland, where the republican vote has increased and the voters have also polarised, wiping out the seats of the traditional ‘moderate’ unionist and nationalist parties (UUP and SDLP). If the hardline unionists of the DUP, as ‘kingmakers’ of a Tory government, are able to wield undue weight in the next parliament, the future for what remains of the Good Friday peace agreement does not look good.

However, with the need to please so many outside her own camp, many of May’s manifesto promises will now be impossible to act on and, with divisions rife within her own party, she will likely find herself having to cobble together an alliance for every single bill she wants to pass through parliament. In all likelihood, the Tory/DUP alliance, if it can be brought together at all, will quite quickly fall apart, and there is every chance that May will be unceremoniously dumped and that a new election will be called before too much time has passed.

So workers can expect to see more animosity, more infighting, more jostling for position within and between the parties, more mudslinging and fearmongering in the media as various factions within the ruling class struggle to come out on top and the whole lot try desperately to work out some kind of coherent plan for dealing with the crisis.

Our tasks

All in all, it is clear that the election has decided nothing. The splits within the ruling class and the bourgeois parties will continue to deepen, and the resulting political chaos will continue to grow. And this is only to be expected, because no changing of the guard is capable of dealing with the root cause of society’s problems: the deepening capitalist crisis of overproduction.

Out of this crisis, however, will also come opportunities. The more the ruling class’s energies are taken up with in-fighting and jostling for position, the more space is likely to open up for workers to put up their own resistance, both within and against the system. The challenge is to organise ourselves to take advantage of the opportunities presented by the weakness and disarray in the enemy’s camp.

As communists, we believe very strongly that workers should fight for better conditions within the system of capitalism. Not to do so would be to give up our humanity altogether and accept our position as mere slaves. Our party is delighted to see that increasing numbers of workers, especially the young, are exercising their voting rights in their desire to promote working-class interests over those of the moneybags.

The communists support every struggle of the working class to fight for improvements in their conditions, but this support seeks at the same time to convince workers of the need for proletarian revolution, not to lull them into the false but reassuring belief that their needs can be met within capitalism. No amount of tweaking at the edges of economic or foreign policy is going to make this parasitic and dying system serve the interests of the working class or cure the chaos in which we now find ourselves.

The programme of the Labour party is, at best, a prayer that the ills of capitalism can be solved within the capitalist system. Our position is that, with the best will in the world, they can’t. Workers’ salvation lies not with Saint Jeremy or Stern Theresa, but with the workers themselves.

Unpalatable as this truth may be, ultimately we will not be able to vote our way out of the crisis. Either the crisis will lead the working class deeper into poverty and war, or workers will organise themselves to defeat the crisis by overthrowing capitalism and building a socialist society that is capable of meeting their needs.