Read part one of this article.

The following extract is taken from Andrei Zhdanov’s article Report on the journals Zvezda and Leningrad, 1947.

*****

We know from the history of Russian literature that the reactionary literary trends to which the symbolists and the acmeists belonged tried time and time again to start a crusade against the great revolutionary-democratic tradition of Russian literature and against its foremost representatives, tried to deprive literature of its high ideological and social significance and to drag it down into the morass of meaninglessness and cheapness.

All these ‘fashionable’ trends have been engulfed and buried with the classes whose ideology they reflected. What, in our Soviet literature, has remained of all these symbolists, acmeists, yellow shirts, jacks-o-diamonds and nichevoki (‘nothingers’)?

Nothing whatever, though their crusades against the great representatives of Russian revolutionary-democratic literature, Delinsky, Dobrolyubov, Chernyshevsky, Herzen, Saltykov-Shchedrin, were launched noisily and pretentiously and just as noisily failed.

The acmeists proclaimed it their motto ‘not to improve life in any way whatever nor to indulge in criticism of it’. Why were they against improving life in any way whatever? Because they liked the old bourgeois-aristocratic life, whereas the revolutionary people were preparing to disturb this life of theirs.

In November 1917 both the ruling classes and their theoreticians and singers were pitched into the dustbin of history.

And now, in the 29th year of the socialist revolution, certain museum specimens reappear all of a sudden and start teaching our young people how to live. The pages of a Leningrad journal are thrown wide open to Akhmatova and she is given carte blanche to poison the minds of the young people with the harmful spirit of her poetry.

One of the issues of Leningrad contains a kind of digest of the works written by Akhmatova between 1909 and 1944. Among the rest of the rubbish, there is a poem she wrote during evacuation in the Great Patriotic War. In this poem she describes her loneliness, the solitude she has to share with a black cat, whose eyes looking at her are like the eyes of the centuries. This is no new theme: Akhmatova wrote about a black cat in 1909, too. This mood of solitude and hopelessness, which is foreign to the spirit of Soviet literature, runs through the whole of Akhmatova’s work.

What has this poetry in common with the interests of our state and people? Nothing whatever. Akhmatova’s work is a matter of the distant past; it is foreign to Soviet life and cannot be tolerated in the pages of our journals.

Our literature is no private enterprise designed to please the fluctuating tastes of the literary market. We are certainly under no obligation to find a place in our literature for tastes and ways that have nothing in common with the moral qualities and attributes of Soviet people.

What instructive value can the works of Akhmatova have for our young people? They can do them nothing but harm. These works can sow nothing but gloom, low spirits, pessimism, a desire to escape the vital problems of social life and turn away from the broad highway of social life and activity into a narrow little world of personal experiences.

How can the upbringing of our young people be entrusted to her? Yet her poems were readily printed, sometimes in Zvezda and sometimes in Leningrad, and were published in volume form. This was a serious political error.

It is only natural, in view of all this, that the works of other writers, who were also beginning to adopt an empty-headed and defeatist tone, should have started to appear in the Leningrad journals. I am thinking of works such as those of Sadofyev and Komissarova. In some of their poems they imitate Akhmatova, cultivating the mood of despondency, boredom and loneliness so dear to her.

Needless to say, such moods, or the extolling of them, can exert only a negative influence on our young people and are bound to poison their minds with a vicious spirit of empty-headedness, despondency and lack of political consciousness.

What would have happened if we had brought our young people up in a spirit of despondency and of disbelief in our cause? We should not have won the Great Patriotic War.

It is precisely because the Soviet state, and our party, with the help of Soviet literature, had brought our young people up in a spirit of optimism and with confidence in their own strength, that we were able to surmount the tremendous difficulties that faced us in the building of socialism and in defeating the Germans and the Japanese.

What does this mean? It means that by printing in its pages cheap and reactionary works devoid of proper ideas, side by side with good works of rich content and cheerful tone, Zvezda became a journal having no clear policy, a journal helping our enemies to corrupt our young people.

The strength of our journals has always lain in their optimistic revolutionary trend, not in eclecticism, empty-headedness and lack of political understanding. Zvezda gave its full sanction to propaganda in favour of doing nothing.

To make matters worse, Zoshchenko seems to have acquired so much power in the Leningrad writers’ organisation that he even used to shout down those who disagreed with him and threaten to lampoon his critics in one of his forthcoming works. He became a sort of literary dictator surrounded by a group of admirers singing his praises.

Well may one ask, on what grounds? Why did you allow such an unnatural and reactionary thing as this to occur?

No wonder Leningrad’s literary journals started giving space to cheap modern bourgeois literature from the West. Some of our men of letters began looking on themselves as not the teachers but the pupils of petty-bourgeois writers, and began to adopt an obsequious and awestruck attitude towards foreign literature.

Is such obsequiousness becoming in us Soviet patriots who have built up the Soviet order, which towers higher a hundredfold, and is better a hundredfold, than any bourgeois order? Is obsequiousness towards the cheap and philistine bourgeois literature of the west becoming in our advanced Soviet literature, the most revolutionary in the world?

Another serious failing in the work of our writers is their ignoring of modern Soviet subjects, which betrays on the one hand a one-sided interest in historical subjects and on the other an attempt to write on meaningless, purely amusing subjects.

To justify their failure to keep pace with great modern Soviet themes, some writers maintain that the time has come to give the people meaningless and ‘entertaining’ literature, to stop bothering about literature’s ideological content.

This conception of our people, of their interests and requirements, is entirely wrong. Our people expect Soviet writers to understand and integrate the vast experience they gained in the Great Patriotic War, to portray and integrate the heroism with which they are now working to rehabilitate the country’s national economy.

A few words on the journal Leningrad: Zoshchenko’s position is even stronger here than in Zvezda, as is Akhmatova’s too. Both of them have become active powers in both journals. Thus Leningrad is responsible for having put its pages at the disposal of such cheap writers as Zoshchenko and such salon poetesses as Akhmatova.

The journal Leningrad has, however, made other mistakes also.

For instance, take the parody of Evgeny Onegin written by one Khazin. This piece is called The Return of Onegin. It is said to be frequently recited on the variety concert platforms of Leningrad.

It is hard to understand why the people of Leningrad allow their city to be vilified from a public platform in such a way as Khazin vilifies it. The purpose of this ‘satire’ is not simple ridicule of the things that happen to Onegin on finding himself in modern Leningrad. The point is that Khazin essays to compare our modern Leningrad with the St Petersburg of Pushkin’s day, and for the worse.

Read just a few lines of this ‘parody’ attentively. Nothing in our modern Leningrad pleases the author. Sneering in malice and derision, he slanders Leningrad and Soviet people. In his opinion, Onegin’s day was a golden age.

Everything is different now: a housing department has appeared, and ration cards and permits. Girls, those ethereal creatures so much admired of Onegin, now regulate the traffic and repair the Leningrad houses and so on and so forth. Let me quote just one passage from this ‘parody’:

Our poor dear Evgeny

Boarded a tram.

Never had his benighted age known

Such a means of transportation.

But fate was kind to Evgeny;

He escaped with only a foot crushed,

And only once, when someone jabbed him

In the stomach, was he called an idiot.

Remembering ancient customs,

He resolved to seek satisfaction in a duel:

He felt in his pocket, but

Someone had taken his gloves,

A frustration that reduced

Onegin to silence and docility.

That is what Leningrad was like before, and what it has turned into: a wretched, uncouth, coarse city; and that is the aspect it presented to poor dear Onegin. It is in this vulgar way that Khazin describes Leningrad and its people.

The idea behind this slanderous parody is harmful, vicious and false.

How could the editorial board of Leningrad have accepted this malicious slander on Leningrad and its magnificent people? How could Khazin have been allowed to appear in the pages of the Leningrad journals?

Take another work, a parody on a parody by Nekrasov, so written as to be a direct insult to the memory of the great poet and public figure Nekrasov, an insult that ought to arouse the indignation of every educated person. Yet Leningrad’s editorial board did not hesitate to print this sordid concoction in its columns.

What else do we find in Leningrad? A foreign anecdote, dull and shallow, apparently lifted from hackneyed anecdote books dating from the late nineteenth century. Is there nothing else for Leningrad to fill its pages with? Is there really nothing to write about in Leningrad?

What about such a subject as the rehabilitation of the city? Wonderful work is being done in Leningrad; the city is healing the wounds inflicted during the siege; the people of Leningrad are imbued with the enthusiasm and emotion of postwar rehabilitation.

Has anything on this appeared in Leningrad? Will the people of the city ever live to see the day when their feats of labour are reflected in the pages of this journal?

Further, let us take the subject of Soviet woman. Is it permissible to cultivate in Soviet readers the disgraceful views on the role and mission of women that are typical of Akhmatova, and not to give a really truthful concept of modern Soviet woman in general and the heroic girls and women of Leningrad in particular, who unflinchingly shouldered the heavy burden of the war years and are now self-sacrificingly working to carry out the difficult tasks presented by the rehabilitation of the city’s economic life?

The situation in the Leningrad section of the Union of Soviet Writers is obviously such that the supply of good work is now insufficient to fill two literary journals. The central committee of the party has therefore decided to cease publication of Leningrad, so as to concentrate all the best literary forces in Zvezda.

This does not mean that Leningrad will not, in suitable circumstances, have a second or even a third journal. The question will be settled by the supply of notable literary works. Should so many appear that there is no room for them in one journal, a second and even a third may be started; it all depends on the intellectual and artistic quality of the works produced by our Leningrad writers.

Such are the grave errors and failings laid bare and detailed in the resolution of the central committee of the Communist Party on the work of Zvezda and Leningrad.

Leninism and literature

What is the cause of these errors and failings?

It is that the editors of the said journals, our Soviet men of letters, and the leaders of our ideological front in Leningrad, have forgotten some of the principal tenets of Leninism as regards literature.

Many writers, and many of those working as responsible editors, or holding important posts in the writers’ union, consider politics to be the business of the government or of the central committee. When it comes to men of letters, engaging in politics is no business of theirs. If a man has done a good, artistic, fine piece of writing, his work should be published even though it contains vicious elements liable to confuse and poison the minds of our young people.

We demand that our comrades, both practising writers and those in positions of literary leadership, should be guided by that without which the Soviet order cannot live, that is to say, by politics, so that our young people may be brought up not in the spirit of do-nothing and don’t care, but in an optimistic revolutionary spirit.

We know that Leninism embodies all the finest traditions of the Russian nineteenth-century revolutionary democrats and that our Soviet culture derives from and is nourished by the critically assimilated cultural heritage of the past.

Through the lips of Lenin and Stalin our party has repeatedly recognised the tremendous significance in the field of literature of the great Russian revolutionary-democratic writers and critics Belinsky, Dobrolyubov, Chernyshevsky, Saltykov-Shchedrin and Plekhanov.

From Belinsky onward, all the best representatives of the revolutionary-democratic Russian intellectuals have denounced ‘pure art’ and ‘art for art’s sake’, and have been the spokesmen of art for the people, demanding that art should have a worthy educational and social significance.

Art cannot cut itself off from the fate of the people. Remember Belinsky’s famous Letter to Gogol, in which the great critic, with all his native passion, castigated Gogol for his attempt to betray the cause of the people and go over to the side of the tsar. Lenin called this letter one of the finest works of the uncensored democratic press, one that has preserved its tremendous literary significance to this day.

Remember Dobrolyubov’s articles, in which the social significance of literature is so powerfully shown. The whole of our Russian revolutionary-democratic journalism is imbued with a deadly hatred of the tsarist order and with the noble aspiration to fight for the people’s fundamental interests, their enlightenment, their culture, their liberation from the fetters of the tsarist regime.

A militant art fighting for the people’s finest ideals – that is how the great representatives of Russian literature envisaged art and literature.

Chernyshevsky, who comes nearest of all the utopian socialists to scientific socialism and whose works were, as Lenin pointed out, ‘indicative of the spirit of the class struggle’, taught us that the task of art was, besides affording a knowledge of life, to teach people how to assess correctly varying social phenomena.

Dobrolyubov, his companion-in-arms and closest friend, remarked that ‘it is not life that follows literary standards, but literature that adapts itself to the trends of life’, and strongly supported the principles of realism, and the national element, in literature, on the grounds that the basis of art is life, that life is the source of creative achievement and that art plays an active part in social life and in shaping social consciousness.

Literature, according to Dobrolyubov, should serve society, should give the people answers to the most urgent problems of the day, should keep abreast of the ideas of its epoch.

Marxist literary criticism, which carries on the great traditions of Belinsky, Chernyshevsky and Dobrolyubov, has always supported realistic art with a social stand.

Plekhanov did a great deal to show up the idealistic and unscientific concept of art and literature and to defend the basic tenets of our great Russian revolutionary democrats, who taught us to regard literature as a means of serving the people.

Lenin was the first to state clearly what attitude towards art and literature advanced social thought should take. Let me remind you of the well-known article, Party organisation and party literature, which he wrote at the end of 1905, and in which he demonstrated with characteristic forcefulness that literature cannot but have a partisan adherence and that it must form an important part of the general proletarian cause.

All the principles on which the development of our Soviet literature is based are to be found in this article.

‘Literature must become partisan literature,’ wrote Lenin. ‘To offset bourgeois customs, to offset the commercial bourgeois press, to offset bourgeois literary careerism and self-seeking, to offset ‘gentlemanly anarchism’ and profit-seeking, the socialist proletariat must put forward the principle of partisan literature, must develop this principle and carry it out in the completest and most integral form.

‘What is this principle of partisan literature? It is not merely that literature cannot, to the socialist proletariat, be a means of profit to individuals or groups; all in all, literature cannot be an individual matter divorced from the general proletarian cause.

Down with the writers who think themselves supermen! Down with non-partisan writers! Literature must become part and parcel of the general proletarian cause …’

And further, from the same article: ‘It is not possible to live in society and remain free of it. The freedom of the bourgeois writer, artist or actor is merely a masked dependence (hypocritically masked perhaps) on the moneybags, on bribes, on allowances.’

Leninism starts from the premise that our literature cannot be apolitical, cannot be ‘art for art’s sake’, but is called upon to play an important and leading part in social life. Hence derives the Leninist principle of partisanship in literature, one of Lenin’s most important contributions to the study of literature.

It follows that the finest aspect of Soviet literature is its carrying on of the best traditions of nineteenth-century Russian literature, traditions established by our great revolutionary democrats Belinsky, Dobrolyubov, Chernyshevsky and Saltykov-Shchedrin, continued by Plekhanov and scientifically elaborated and substantiated by Lenin and Stalin.

Nekrasov declared his poetry to be inspired by ‘the muse of sorrow and vengeance’. Chernyshevsky and Dobrolyubov regarded literature as sacred service to the people.

Under the tsarist system, the finest representatives among the democratic Russian intellectuals perished for these high and noble ideas, or willingly risked sentences of exile and hard labour.

How can these glorious traditions be forgotten? How can we pass them over, how can we let the Akhmatovas and the Zoshchenkos disseminate the reactionary catchword ‘art for art’s sake’, how can we let them, behind their mask of impartiality, impose ideas on us that are alien to the spirit of the Soviet people?

Leninism recognises the tremendous significance of our literature as a means of reforming society. Were our Soviet literature to allow any falling off in its tremendous educational role, the result would be retrogression, a return ‘to the stone age’.

Comrade Stalin has called our writers engineers of the human soul. This definition has a profound meaning. It speaks of the enormous educational responsibility Soviet writers bear, responsibility for the training of Soviet youth, responsibility for seeing to it that bad literary work is not tolerated.

There are people who find it strange that the central committee should have taken such stringent measures as regards literature. It is not what we are accustomed to.

If mistakes have been allowed to occur in industrial production, or if the production programme for consumer goods has not been carried out, or if the supply of timber falls behind schedule, then it is considered natural for the people responsible to be publicly reprimanded. But if mistakes have been allowed to occur as regards the proper influencing of human souls, as regards the upbringing of the young, then such mistakes may be tolerated.

And yet, is not this a bitterer pill to swallow than the non-fulfilment of a production programme or the failure to carry out a production task? The purpose of the central committee’s resolution is to bring the ideological front into line with all the other sectors of our work.

On the ideological front, serious gaps and failings have recently become apparent. Suffice it to remind you of the backwardness of our cinematic art, and of the way our theatre repertoires have got cluttered up with poor dramatic works, not to mention what has been going on in Zvezda and Leningrad.

The central committee has been compelled to interfere and firmly to set matters right. It has no right to deal gently with those who forget their duties with regard to the people, to the upbringing of our young people.

If we wish to draw our members’ attention to questions relating to ideological work and to set matters right in this field, to establish a clear line in this work, then we must criticise the mistakes and failings in ideological work severely, as befits Soviet people, as befit Bolsheviks. Only then shall we be able to set matters right.

There are men of letters who reason thus: since during the war, when few books were printed, the people were hungry for reading matter, the reader will now swallow anything, even though the flavour be a trifle tainted.

This is not in fact true, and we cannot put up with any old literature that may be palmed off on us by undiscriminating authors, editors and publishers. From Soviet writers the Soviet people expect reliable ideological armament, spiritual food to further the fulfilment of construction and rehabilitation plans and to promote the development of our country’s national economy.

The Soviet people desire the satisfaction of their cultural and ideological needs, and make great demands on men of letters.

During the war force of circumstances prevented us from satisfying these vital needs. The people want to understand current events. Their cultural and intellectual level has risen. They are often dissatisfied with the quality of the works of art and literature appearing in our country. Certain literary workers on the ideological front have not understood this and are unwilling to do so.

The tastes and demands of our people have risen to a very high level, and anyone who cannot or will not rise to this level is going to be left behind. The mission of literature is not merely to keep abreast of the people’s demands but to be always in the vanguard.

It is essential that literature should develop the people’s tastes, raise their demands higher and higher still, enrich them with new ideas and lead them forward. Anyone who cannot keep pace with the people, satisfy their growing demands and cope with the task of developing Soviet culture, will inevitably find himself no longer in demand.

The lack of ideological principles shown by leading workers on Zvezda and Leningrad has led to a second serious mistake. Certain of our leading workers have, in their relations with various authors, set personal interests, the interests of friendship, above those of the political education of the Soviet people or these authors’ political tendencies.

It is said that many ideologically harmful and from a literary point of view weak productions are allowed to be published because the editor does not like to hurt the author’s feelings. In the eyes of such workers it is better to sacrifice the interests of the people and of the state than to hurt some author’s feelings.

This is an entirely wrong and politically dangerous principle. It is like swopping a million roubles for a kopeck.

The central committee of the party points out in its resolution the grave danger in substituting for relations based on principle those based on personal friendship.

The relations of personal friendship regardless of principle prevailing among certain of our men of letters have played a profoundly negative part, led to a falling off in the ideological level of many literary works and made it easier for this field to be entered by persons foreign to the spirit of Soviet literature.

The absence of any criticism on the part of the leaders of the Leningrad ideological front or of the editors of the Leningrad journals has done a great deal of harm; the substitution of relations of friendship for those based on principle has been made at the expense of the people’s interests.

Comrade Stalin teaches us that if we wish to conserve our human resources, to guide and teach the people, we must not be afraid of hurting the feelings of single individuals or fear bold, frank, objective criticism founded on principle.

Any organisation, literary or other, is liable to degenerate without criticism, any ailment is liable to be driven deeper in and become harder to cope with.

Only bold frank criticism can help our people and overcome any failings in their work. Where criticism is lacking, stagnation and inertia set in, leaving no room for progress.

Comrade Stalin has repeatedly pointed out that one of the most important conditions for our development is for every Soviet citizen to sum up the results of his work every day, to assess himself fearlessly, to analyse his work bravely, and to criticise his own mistakes and failings, pondering how to achieve better results and constantly striving for self-improvement.

This applies just as much to men of letters as to any other workers. The man who is afraid of any criticism of his work is a despicable coward deserving no respect from the people.

An uncritical attitude, and the substitution of relations of personal friendship for those based on principle, are very prevalent on the board of the Union of Soviet Writers.

The board, and its chairman Comrade Tikhonov in particular, are to blame for the bad state of affairs revealed in Zvezda and Leningrad, in that they not only made no attempt to prevent the harmful influence of Zoshchenko, Akhmatova and other un-Soviet writers penetrating into Soviet literature, but even readily permitted styles and tendencies alien to the spirit of Soviet literature to find a place in our journals.

Another factor contributing to the failings of the Leningrad journals was the state of irresponsibility that developed among the editors of these journals, the situation being such that no-one knew who had the overall responsibility for the journal or for its various departments, so that any sort of order, even the most rudimentary, was impossible.

The central committee has, therefore, in its resolution appointed to Zvezda an editor-in-chief, who is to be held responsible for the journal’s policy and for the ideological level and literary quality of its contents.

Disorder and anarchy are no more to be tolerated in the issuing of literary publications than in any other enterprise. A clear-cut responsibility for the journal’s policy and contents must be established.

You must restore the glorious traditions of Leningrad’s literature and ideological front. It is a sad and painful thing to have to admit that the Leningrad journals, which had always sponsored the most advanced ideas, have come to harbour empty-headedness and cheapness.

The honour of Leningrad as a leading ideological and cultural centre must be restored. We must remember that Leningrad was the cradle of the Bolshevik Leninist organisations. It was here that Lenin and Stalin laid the foundations of the Bolshevik party, the Bolshevik world outlook and Bolshevik culture.

It is a point of honour for Leningrad writers and party members to restore and carry further these glorious traditions. It is the task of the Leningrad workers on the ideological front, and of the writers above all, to drive empty-headedness and cheapness out of Leningrad literature, to raise aloft the banner of Soviet literature, to seize every opportunity for ideological and literary development, not to leave up-to-date themes untreated, to keep pace with the people’s demands, to encourage in every possible way the bold criticism of their own failings, criticism containing no element of toadying and not based on friendships and group-loyalties – a genuine, bold, independent, ideological, Bolshevik criticism.

By now it should be clear to you what a serious oversight the Leningrad city committee of the party, and particularly its propaganda department and propaganda secretary Comrade Shirokov (who was put in charge of ideological work and bears the main responsibility for the failure of these journals), have been guilty of.

The Leningrad committee of the party committed a grave political error when it passed its resolution at the end of June on Zvezda’s new editorial board, in which Zoshchenko was included. Political blindness is the only possible explanation of the fact that Comrades Kapustin (secretary of the city committee of the party) and Shirokov (the city committee’s propaganda secretary) should have agreed to such an erroneous decision.

All these mistakes must, I repeat, be set right as quickly and firmly as possible, to enable Leningrad to resume its participation in the ideological life of our party.

We all love Leningrad; we all love our Leningrad party organisation as being one of our party’s leading detachments. Literary adventurers of all sorts who would like to make use of Leningrad for their own ends must find no refuge here.

Zoshchenko, Akhmatova and the like have no fondness for Soviet Leningrad. It is other social and political ways and another ideology that they would like to see entrenched here. The visions dazzling their eyes are those of old St Petersburg, with the Bronze Horseman as its symbol.

We, on the contrary, love Soviet Leningrad, Leningrad as the foremost centre of Soviet culture. Our ancestors are the glorious band of great revolutionary and democratic figures who came from Leningrad and whose direct descendants we are.

Modern Leningrad’s glorious traditions are a continuation of those great revolutionary-democratic traditions, which we would not exchange for anything else in the world.

Let the Leningrad party members analyse their mistakes boldly, with no backward glances, no taking it easy so as to straighten things out in the best and quickest way possible and to carry our ideological work forward.

The Leningrad Bolsheviks must once more take their place in the ranks of the initiators, of the leaders in the shaping of Soviet ideology and Soviet social consciousness.

How could the Leningrad city committee of the party have permitted such a situation to arise on the ideological front? It had evidently become so engrossed in day-to-day practical work on the rehabilitation of the city and the development of its industry that it forgot the importance of ideological and educational work.

This forgetfulness has cost the Leningrad organisation dear. Ideological work must not be forgotten. Our people’s spiritual wealth is no less important than their material wealth.

We cannot live blindly, taking no thought for the morrow, either in the field of material production or in the ideological field. To such an extent have our Soviet people developed that they are not going to swallow whatsoever spiritual food may be dumped on them.

Such workers in art and culture as do not change and cannot satisfy the people’s growing needs may forfeit the people’s confidence before long.

Our Soviet literature lives and must live in the interests of our country and of our people alone. Literature is a concern near and dear to the people. So the people consider our every success, every important work of literature, as a victory of their own. Every successful work may therefore be compared with a battle won, or with a great victory on the economic front.

And conversely, every failure of Soviet literature hurts and wounds the people, the party and the state profoundly.

This is what the central committee was thinking of in passing its resolution, for the central committee watches over the interests of the people and of their literature, and is very greatly concerned about the present state of affairs among Leningrad writers.

People who have not taken up any ideological stand would like to cut away the foundations from under the Leningrad detachment of literary workers, demolish their work’s ideological aspect and deprive the Leningrad writers’ work of its significance as a means of social reform.

But the central committee is confident that Leningrad’s men of letters will nevertheless find in themselves the strength to put a stop to any attempts to divert Leningrad’s literature detachment and journals into a groove of empty-headedness and lack of principle and political consciousness.

You have been set in the foremost line of the ideological front, you are facing tremendous and internationally significant tasks; and this should intensify every genuine Soviet writer’s sense of responsibility to his people, his state and his party, and his sense of the importance of the duty he is carrying out.

Whether our successes are won within our own country or in the international arena, the bourgeois world does not like them.

As a result of the second world war the position of socialism has been strengthened. The question of socialism has been put down on the agenda of many countries in Europe.

This displeases the imperialists of every hue: they fear socialism and our socialist country, an example to the whole of progressive mankind.

The imperialists and their ideological henchmen, writers, journalists, politicians and diplomats, are trying to slander our country in every way open to them, to put it in a false light, to vilify socialism.

The task of Soviet literature in these conditions is not only to return blow for blow to all this vile slander and all these attacks on our Soviet culture and on socialism, but also to make a frontal attack on degenerating and decaying bourgeois culture.

However fine may be the external appearance of the work of the fashionable modern bourgeois writers in America and western Europe, and of their film directors and theatrical producers, they can neither save nor better their bourgeois culture, for its moral basis is rotten and decaying. It has been placed at the service of capitalist private ownership, of the selfish and egocentric interests of the top layer of bourgeois society.

A swarm of bourgeois writers, film directors and theatrical producers are trying to draw the attention of the progressive strata of society away from the acute problems of social and political struggle and to divert it into a groove of cheap meaningless art and literature, treating of gangsters and showgirls and glorifying the adulterer and the adventures of crooks and gamblers.

Is it fitting for us Soviet patriots, the representatives of advanced Soviet culture, to play the part of admirers or disciples of bourgeois culture?

Our literature, reflecting an order on a higher level than any bourgeois-democratic order and a culture manifoldly superior to bourgeois culture, has, it goes without saying, the right to teach the new universal morals to others.

Where is another such people or country as ours to be found? Where are such splendid human qualities to be found as our Soviet people displayed in the Great Patriotic War and are displaying every day in the labour of converting our economy to peaceful development and material and cultural rehabilitation?

Our people are climbing higher and higher every day. No longer are we the Russians we were before 1917; no longer is our Russia the same, no longer is our character the same. We have changed and grown along with the great changes that have transfigured our country from its very foundations.

Showing these great new qualities of the Soviet people, not only showing our people as they are today, but glancing into their future and helping to light up the way ahead, is the task of every conscientious Soviet writer.

A writer cannot tag along in the wake of events; it is for him to march in the foremost ranks of the people and point out to them the path of their development. He must educate the people and arm them ideologically, guiding himself by the method of socialist realism, studying our life attentively and conscientiously and trying to gain a deeper understanding of the processes of our development.

At the same time as we select Soviet man’s finest feelings and qualities and reveal his future to him, we must show our people what they should not be like and castigate the survivals from yesterday that are hindering the Soviet people’s progress. Soviet writers must help the people, the state and the party to educate our young people to be optimistic, to have confidence in their own strength and to fear no difficulties.

Hard as bourgeois politicians and writers may strive to conceal the truth of the achievements of the Soviet order and Soviet culture, hard as they may strive to erect an iron curtain to keep the truth about the Soviet Union from penetrating abroad, hard as they may strive to belittle the genuine growth and scope of Soviet culture, all their efforts are foredoomed to failure.

We know our culture’s strength and advantages very well. Suffice it to recall the great success of our cultural delegations abroad, of our physical culture parades and so on. It is not for us to kowtow to all things foreign or to stand passively on the defensive.

If in their heyday the feudal order and then the bourgeoisie were able to create art and literature asserting the establishment of the new order and singing its praises, then we who form a new socialist order embodying all that is best in the history of civilisation and culture are yet fitter to create the most advanced literature in the world, far surpassing the finest literary examples of former times.

What is it that the central committee requests and wishes?

The central committee of the party wishes the Leningrad party members and writers to understand clearly that the time has come for us to raise our ideological work to a high level. The young Soviet generation will be called upon to consolidate the strength and power of the socialist Soviet order, to make full use of the motive forces of Soviet society to promote our material and cultural progress.

To carry out these great tasks, the young generation must be brought up to be steadfast and cheerful, not to balk at difficulties but to meet and know how to surmount them. Our people must be educated people of high ideals, tastes and moral and cultural demands.

It is necessary to this end that our literature, our journals, should not hold aloof from the tasks of the day but should help the party and the people to educate our young people in the spirit of supreme devotion to the Soviet order and service in the interests of the people.

Soviet writers, and all our ideological workers, are now standing in the foremost fighting line; for our tasks on the ideological front, and those of literature above all, have not been removed but, on the contrary, are growing more important in conditions of peaceful development.

It is not a removal of literature from contemporary problems that the people, the state and the party want, but the active incursion of literature into every aspect of Soviet life.

Bolsheviks set a high value on literature and have a clear perception of its great historical mission of reinforcing the people’s moral and political unity, educating them and consolidating their ranks. The central committee wishes us to feed the human spirit abundantly, regarding the attainment of cultural wealth as a chief task of socialism.

The central committee of the party feels sure the Leningrad detachment of Soviet literature is morally and politically sound and will quickly set its mistakes right and take its due place in the ranks of Soviet literature.

The central committee feels sure the failings in the work of Leningrad writers will be overcome and the ideological work of the Leningrad party organisation soon raised to the level now required in the interests of the party, the people and the state.

In defence of Marxist philosophy

The life of Andrei Zhdanov was the life of an outstanding Marxist Leninist. Zhdanov was true to Marxism and, like Lenin, waged a relentless fight against the enemies of Marxism; the enemies of the proletariat. He never became that which he despised, a “toothless vegetarian” in philosophy.

One of his last major theoretical-practical speeches was made at a conference of Soviet philosophical workers in 1947. Summing up the corruption of bourgeois ideology after the victory of the USSR in the Great Patriotic War, Zhdanov said:

Today the centre of the struggle against Marxism has shifted to America and Britain. All the forces of obscurantism and reaction have today been placed at the service of the struggle against Marxism.

Brought out anew and placed at the service of bourgeois philosophy are the instruments of atom-dollar democracy, the outworn armour of obscurantism and clericalism: the Vatican and racist theory, rabid nationalism and decayed idealist philosophy, the mercenary yellow press and depraved bourgeois art.

But apparently all these are not enough. Today, under the banner of ‘ideological’ struggle against Marxism, large reserves are being mobilised. Gangsters, pimps, spies and criminal elements are recruited.

Let me take, at random, a recent example. As was reported a few days ago in Izvestia, the journal Les Temps Modernes, edited by the existentialist, Sartre, lauds as some new revelation a book by the writer Jean Genet, The Diary of a Thief, which opens with the words:

Treason, theft and homosexuality – these will be my key topics. There exists an organic connection between my taste for treason, the occupation of the thief, and my amorous adventures.

The author manifestly knows his business. The plays of the Jean Genet are presented with much glitter on the Parisian stage and Jean Genet himself is showered with invitations to visit America. Such is the ‘last word’ of bourgeois culture.

We know from the experience of our victory over fascism into what a blind alley idealist philosophy has led whole nations. Now it appears in its new, repulsively ugly character which reflects the whole depth, baseness and loathsomeness of the decay of the bourgeoisie.

Pimps and depraved criminals as philosophers – this is indeed the limit of decay and ruin. Nevertheless, these forces still have life, are still capable of poisoning the consciousness of the masses.

Contemporary bourgeois science supplies clericalism and fideism with new arguments which must be mercilessly exposed. We can take as an example the English astronomer Eddington’s theory of the physical constants of the universe, which leads directly to the Pythagorean mysticism of numbers which, from mathematical formulae, deduces such ‘essential constants’ as the apocalyptic number 666, etc.

Many followers of Einstein, in their failure to understand the dialectical process of knowledge, the relationship of absolute and relative truth, transpose the results of the study of the laws of motion of the finite, limited sphere of the universe to the whole infinite universe and arrive at the idea of the finite nature of the world, its limitedness in time and space.

The astronomer Milne has even ‘calculated’ that the world was created 2 billion years ago. It would probably be correct to apply to those English scientists the words of their great countryman, the philosopher Bacon, about those who turn the impotence of their science into a libel against nature.

In like measure, the Kantian subterfuges of contemporary bourgeois atomic physicists lead them to deductions of the ‘free will’ of the electron and to attempts to represent matter as only some combination of waves and other such nonsense.

Here is a colossal field of activity for our philosophers, who should analyse and generalise the results of contemporary natural science, remembering the advice of Engels that materialism ‘with each epoch-making discovery, even in the sphere of natural science … has to change its form’. (Frederick Engels, Ludwig Feuerbach, chapter 2)

Upon whom, if not upon us – the land, of victorious Marxism and its philosophers – devolves the task of heading the struggle against corrupt and base bourgeois ideology? Who if not we should strike crushing blows against it? (On philosophy: speech at a conference of Soviet philosophical workers)

Death and legacy

Comrade Zhdanov didn’t live long after making this speech; he died the following August in 1948. His contemporaries Pospelov and Gorkin lived nearly into the 1980s and had the peak of their careers in the 1950s and 60s.

Zhdanov died early, as did his close comrade Shcherbakov, and their deaths were reported in 1953 as being attributed to the doctors’ plot, which, after the death of Stalin in March 1953 was said to have been a fabrication of Lavrentiy Beria and Viktor Abakumov.

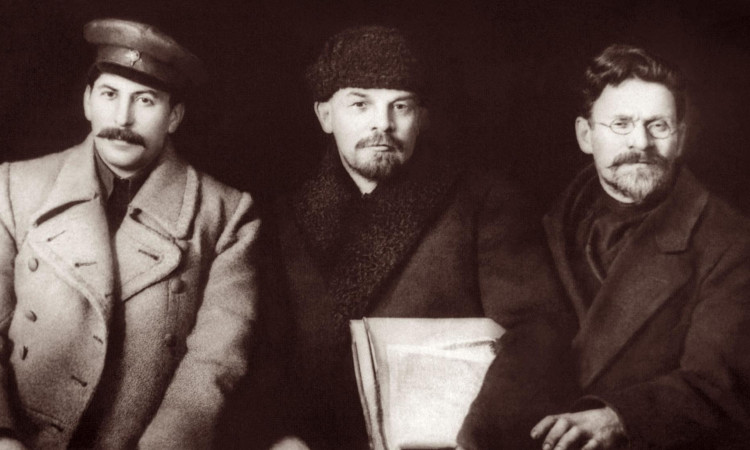

Zhdanov, Shcherbakov and Stalin all appear to have died awaiting medical treatment. Abakumov and Beria died violent deaths. Andrei Zhdanov was survived by his son Yuri, who, as a scientific worker in the USSR, went on to become a professor at the Rostov university.

In remembering Andrei Zhdanov, we remember him as a great Bolshevik, a Soviet statesman and talented propagandist. He was a product of the Great October Socialist Revolution, and taking him in his historical context, far from diminishing his historical significance, raises him up.