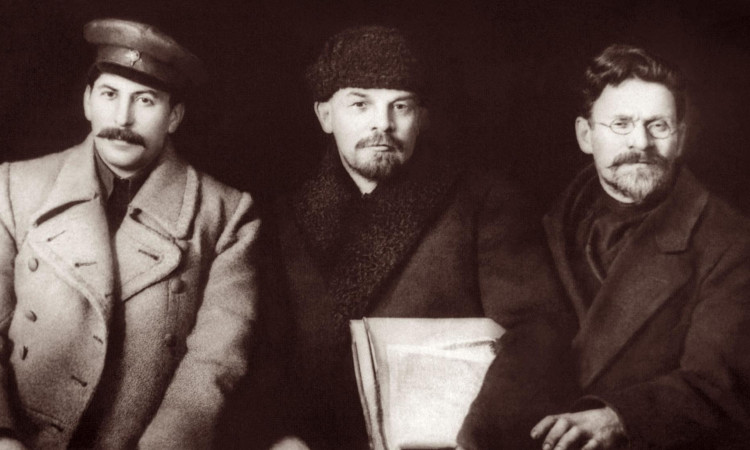

Former Soviet leader Josef Stalin’s approval rating has hit a record high of 70 percent amongst Russians, according to a study published by the Levada polling centre. (Stalin’s approval rating among Russians hits record high, The Moscow Times, 16 April 2019)

We are used to reading opinion polls, and being justifiably sceptical about their findings. Very often, a tiny proportion of the public is polled, and the methodology is key to determining the responses and therefore the outcomes. In ‘the west’, so-called ‘opinion polling’ is in general a technique of population manipulation, rather than one of enquiring science.

In this case, however, we note the general hostility of those conducting such polls – as evidenced by the liberal sprinkling of their reporting with the terms ‘regime’ and ‘dictator’ in relation to the socialist and workers’ states, while they refer to the corrupt capitalist kleptocracies now installed as having brought the great benefits of ‘freedom, jeans, open borders and coca-cola’. Understanding that bourgeois biases were stacked against an accurate recording of the people’s hatred of their present exploitation, we can begin to glimpse a greater truth that lies beneath.

With this in mind, it is worth examining some of the opinion polls of the peoples of the former socialist countries, 30 years on from the counter-revolution.

Over the past decade, polls have been conducted in each of the former democratic republics, allowing us to gauge their experience of the wonders of free-market (ie, monopoly) capitalism. A number of well-known western-European capitalist journals seem to be shocked at their reported results. Bourgeois journalists couch their own surprise in customary cynicism and dismiss the longing of eastern European workers for the return of the decency and optimism of their lost socialist systems as ‘nostalgia’. In Germany, they have even coined the term ‘Ostalgia’ – a longing for the return of the socialist (east) German Democratic Republic (GDR).

Subtly twisting words to suit their agenda, these reporters attempt to cover up the truth when discussing the reality of working-class power and actual opinions of east European workers, derived from the lived experience of workers from the former socialist states. This kind of con game has long existed when discussing any country that doesn’t have a system of government of which western capitalism approves.

The full articles are linked to, and we invite you to read them – bearing in mind that every piece of data is used as a pretext for a subjective and irrelevant conclusion in order to launch an unwarranted attack on socialism. If the youth want socialism, they are ‘young and naive and not experienced enough in life’. If the old that lived under socialism want their socialist systems back, they are ‘nostalgic’ fossils, lamenting for their lost youth.

If we ignore the commentary and listen instead to the source, we will find that our old comrades – who have lived and experienced both socialism and the capitalist reaction, counter-revolution and restoration – themselves provide detailed and nuanced reasons for preferring socialism.

This is all the more remarkable given that most of those old enough to have lived under socialist systems in Europe did so when revisionism was already busy uprooting the gains of the planned economy and preparing the necessary conditions for the counter-revolution. In many cases, the years they experienced were the years of relative stagnation and decline (although the socialist countries never experienced absolute recession before capitalist restoration) that paved the way for full counter-revolution.

Russia and the former Soviet union

“The majority of Russians polled in a 2016 study said they would prefer living under the old Soviet Union and would like to see the socialist system and the Soviet state restored.” (Most Russians prefer return of Soviet Union and socialism, Telesur, 19 August 2017)

Ex-Soviet bloc

“Reflecting back on the break-up of the Soviet Union that happened 22 years ago next week, residents in seven out of 11 countries that were part of the union are more likely to believe its collapse harmed their countries than benefited them. Only Azerbaijanis, Kazakhstanis, and Turkmens are more likely to see benefit than harm from the break-up. Georgians are divided.” (Former Soviet countries see more harm from break-up, Gallup, 19 December 2013)

East Germany

“Today, 20 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, 57 percent, or an absolute majority, of east Germans defend the former east Germany … ‘life was good there’, say 49 percent of those polled. Eight percent of east Germans flatly oppose all criticism of their former home.” (Majority of east Germans feel life better under communism by Julia Bonstein, Spiegel, 3 July 2009)

Hungary

“A remarkable 72 percent of Hungarians say that most people in their country are actually worse off today economically than they were under communism … This is the result of almost universal displeasure with the economy. Fully 94 percent describe the country’s economy as bad, the highest level of economic discontent in the hard hit region of central and eastern Europe … The public is even more negative toward Hungary’s integration into Europe; 71 percent say their country has been weakened by the process.” (Hungary: Better off under communism? Pew Research, 28 April 2010)

Czech Republic

“Roughly 28 percent of Czechs say they were better off under the communist regime … Only 23 percent said they had a better life now.

“More goods in shops, open borders and better cultural offer are considered the biggest successes of the system that was installed after 1989.

“On the other hand, the voucher privatisation, the worsening of human relations and work of the civil service are its biggest flaws, most Czechs said.” (Many Czechs say they had better life under communism, Prague Daily Monitor, 21 November 2011)

The former Yugoslavia

“A poll shows that as many as 81 percent of Serbians believe they lived best in the former Yugoslavia ‘during the time of socialism’ …

“Forty-five percent said they trusted social institutions most under communism with 23 percent choosing the 2001-03 period when Zoran Djinđic was prime minister. Only 19 percent selected present-day institutions.” (Serbia poll: Life was better under Tito, Balkan Insight, 24 December 2010)

People in other parts of the former Yugoslavis, scarred by the ethnic wars from the 1990s and still outside the EU, are nostalgic for the socialist era of Josip Broz Tito when, unlike now, they travelled across Europe without visas.

“Everything was better then. There was no street crime, jobs were safe and salaries were enough for decent living,” said Belgrade pensioner Koviljka Markovic, 70. “Today I can hardly survive with my pension of 250 euros ($370 a month).” (In eastern Europe , people pine for socialism by Anna Muderva Reuters, 8 November 2009)

Romania

A 2010 poll found that 41 percent of the respondents would have voted for Ceausescu, had he run for the position of president. And 63 percent of the survey participants said their life was better during communism, while only 23 percent attested that their life was worse then.

Some 68 percent declared that communism was a good idea, just one that had been poorly applied. (In Romania, opinion polls show nostalgia for communism by Elena Dragomir, Balkan Analysis, 2011)

Ukraine, Lithuania and Bulgaria

“The poll showed 30 percent of Ukrainians approved of the change to democracy in 2009, down from 72 percent in 1991.

“In Bulgaria and Lithuania the slide was to just over half the population from nearer three-quarters in 1991.” (In eastern Europe, people pine for socialism, Reuters, 8 November 2009)

“In Bulgaria, the 33-year rule of the late dictator Todor Zhivkov [1954-89] begins to seem a golden era to some in comparison with the raging corruption and crime that followed his demise.

“Over 60 percent say they lived better in the past, even though shopping queues were routine, social connections were the only way to obtain more valuable goods, jeans and coca-cola were off-limits and it took up to 10 years’ waiting to buy a car.

“‘For part of the Bulgarians (social) security turned out to be more precious than freedom,’ wrote historians Andrei Pantev and Bozhidar Gavrilov.” (Reuters, op cit)

Why people miss socialism

It’s seemingly easy for the bourgeois press, who have to report these unfavourable findings to dismiss them as mere nostalgia. “Oh everyone loved their youth,” they clamour, “it is their youth they are nostalgic for, not socialism!”

It’s therefore worth taking a look at what people themselves have to say about their lived realities.

“Most east German citizens had a nice life,” says one former citizen, Mr Birger. “I certainly don’t think that it’s better here [reunified Germany] … The people who live on the poverty line today also lack the freedom to travel.” [We note that the ‘freedom to travel’ was denied not by the eastern republics but by the aggressive encircling imperialist powers, who put the entire existence of the socialist nations on a war footing, as they continue to do with the citizens of north Korea and Cuba, among others, today.]

“From today’s perspective, I believe that we were driven out of paradise when the wall came down,” one person writes, and a 38-year-old man “thanks God” that he was able to experience living in the GDR, noting that it wasn’t until after German reunification that he witnessed people who feared for their existence, beggars or homeless people. (Spiegel, op cit)

In the case of the GDR, it doesn’t seem to be mere nostalgia talking. It is far better to have a secure life and dignified existence without poverty than to have the ‘freedom’ to wander from town to town, half starving and homeless, or be forced to journey to a foreign land to offer your life and labour for cheap exploitation as your domestic economy has collapsed under the direction of the local kleptocrats and imperialist financiers. In any event, travel within the socialist world was possible and every worker had the right to long and well-paid holidays, maternity leave, carer and sick leave, and more.

What is important here is that an average worker interviewed does not go along with the propaganda narrative of the author. Political scientist Klaus Schroeder, director of an institute at Berlin’s Free university that studies the former communist state is cited in the Spiegel article, admitting: “I am afraid that a majority of eastern Germans do not identify with the current [capitalist and imperialist] sociopolitical system.”

Another point of attack we often see in the bourgeois press is that those who miss their socialist system do so because they were the lazy and untalented elements who therefore enjoyed the security of the state. In fact, a successful businessman interviewed in the article says that although he has personally done well, he is unhappy with unequal wages and pensions, and misses “that feeling of companionship and solidarity”.

Succinctly summing up bourgeois democracy, he says: “As far as I’m concerned, what we had in those days was less of a dictatorship than what we have today.” And he concludes that, as one of the fortunate ones: “I’m better off today than I was before, but I am not more satisfied.”

Speaking of Romania, the Balkan Analysis article concludes that it is not some nostalgia for their communist past that makes people long for socialism, but the fact that “people have felt increasing social and economic pressures and therefore their desire for social security guarantees has increased, regardless of education levels, age or social status”. In other words, economic insecurity has worsened under capitalism, bringing with it an increase in social dislocation, poverty, crime and unhappiness.

For the Russians, the case is simple: in 2017, Russians were spending more than half their income on food. The return of capitalism has meant a complete stripping away of any security for the vast majority and incredible enrichment for a miniscule minority.

Bulgarians are now also enjoying the ‘freedom’ to spend the bulk of their income on food: “We lived better in the past,” says 31-year-old Anelia Beeva. “We went on holidays to the coast and the mountains, there were plenty of clothes, shoes, food. And now the biggest chunk of our incomes is spent on food. People with university degrees are unemployed and many go abroad.” (Reuters, op cit)

“Looking on the surface, I see new buildings, shops, shiny cars. But people have become sadder, more aggressive and unhappy,” says renowned Bulgarian artist Nikola Manev.

Disillusionment with bourgeois democracy

This exponential rise in poverty and disempowerment has gone hand in glove with a disillusionment with bourgeois democracy. Just two countries polled out of the eight countries here were barely ‘satisfied’ with their democracy. (Hungary dissatisfied with democracy, but not its ideals, Pew, 7 April 2010)

Another common myth the bourgeois press propagated before the overthrow of socialism in 1989 was that eastern Europe was somehow imprisoned by its political and economic links with the USSR. The term ‘captive nations’ was ubiquitous in the bourgeois press. The president of the US was required every year to declare something called ‘Captive Nations Week’.

The bourgeois press and its propagandists continue to turn reality on its head, maintaining that eastern Europe was ‘free’ before the Red Army liberated it from Nazi occupation at the end of WW2, and that the new people’s democracies that later united in a security alliance (the Warsaw Pact) to defend themselves from the belligerent imperialist Nato bloc (whose bloodstained record is well known to our readers) was a prison of nations. In fact, before WW1, all of those states (with the exception of Czechoslovakia, which was so nonchalantly ceded to fascist Germany in 1939 under the Nazi-British pact sealed by British prime minister Neville Chamberlain) were ruled by oppressive and dictatorial monarchs or despots of one kind or another.

This disillusionment with bourgeois democracy can be seen in Hungary, for example. Seventy percent of Hungarians think it is very important to live in a country with honest multi-party elections, but only 17 percent believe this describes ‘democratic’ Hungary well. This also shows how, that despite their anger, the Hungarian proletariat have not quite seen off the fraud of the ‘multi-party’ bourgeois system, which provides a cover for the fact that behind the parties lies one ruling class that cannot be voted out of power.

Liberals who read this worry about a ‘disillusionment with democracy’, missing the point that bourgeois democracy is an illusion of democracy. In the west, you can change the ruling party or president but you can’t change the policies. Democracy in the former socialist republics has meant the policies of privatisation of public industry and services – the seizure of wealth that had been built up by the people and was formerly used only to benefit the people, but which are now being asset-stripped and turned into vehicles for profit-making. Capitalist restoration has brought a parasitic outgrowth of rentier cliques, whose only interest is in exploiting the national economy and leeching from its citizenry whatever they can get their blood-soaked hands on.

The capitalist counter-revolution: a modern imperialist holocaust

Those intellectuals and counter-revolutionaries who assisted in the dismantling socialism in Europe and the USSR had hopes of joining the parasitic imperialist club and living like the millionaire class of the USA, Britain and Germany. Instead, their people have become like those of capitalist Mexico – a source of cheap labour for western European and North American capital to exploit for superprofits, whether utilised in situ, or transported abroad.

After the counter-revolution, eastern Europe was systematically de-industrialised. Its formerly free states became new colonies – places to dump western goods, giving a much-needed shot-in the arm to global capitalism, which was just then heading into deepening recession. And with the de-industrialisation of eastern Europe’s economies, jobs were destroyed, forcing much of the young and able-bodied workforce to pack their bags and head for Germany, Britain and France, migrating to the centres of imperialism to find work.

The dire economic situation in many of the former socialist countries was accompanied by a historically unprecedented demographic decline. The return of the ills of unemployment, classical capitalist poverty and the desperation they bring have dragged all the ugly features of capitalist exploitation in their wake: mass drug-addiction, tuberculosis, HIV, prostitution, violence, crime and mental illness.

The birth rate has plummeted while life expectancy has declined by seven years in the territories of the former USSR and abortion rates have soared. This is rarely talked about, but represents a real capitalist holocaust and the deaths of unknown millions of European workers.

As mass privatisation and de-industrialisation were forced on the former German Democratic Republic, that once prosperous and proud nation required west-German subsidies of €130bn annually. Without employment prospects and with their society in ruins, east Germans migrated en masse. What freedom! A stunning population decrease of 2.2 million people from 16.7 million in mid-1989 to 14.5 million in 2005. (Communist nostalgia in eastern Europe: longing for the past by Kurt Biray, Open Democracy, 10 November 2015)

In Bulgaria, the devastating ramifications of economic privatisation and ‘democratic transition’ translated into the loss of jobs and professional occupations in the country’s villages. Mike Donkin, a BBC reporter and journalist, said in 2006 that Bulgaria had the fastest rate of population decline in all of Europe, “and the sense of abandonment is even greater in the countryside … Scattered across the landscape now are dozens of deserted or almost deserted villages.” (Maria Todorova and Zsuzsa Gille, Post-Communist Nostalgia, 2010)

The liquidation of collective farms reduced workers who remained in the countryside to subsistence farming and 19th-century production techniques, leading the young to leave not only the countryside but also the country. No wonder Bulgarians long to return to their lost socialist paradise.

A similar decline has been suffered in Poland. “As people leave, the economy is suppressed which encourages yet more people to up sticks and seek better opportunities abroad.

“And of course it tends to be the most entrepreneurial who leave, while more conservative-minded workers stay behind. Job-creating businesses which might have been set up in Warsaw or Krakow end up being established in London or Berlin.” (Poland asking workers to come home is shocking indictment of EU membership says Ross Clark, The Express, 24 August 2019)

The author claims this is an indictment of the European Union. In fact, it is an indictment of capitalism.

The Polish economy was hit particularly hard by the 2008/9 crisis, yet for the economy to be smaller in 2015 than it was in 2008 is an indication of the extent of the plundering of east Europe’s economies since the fall of socialism.

These results are not chance occurrences; they stem from the anarchy of the market in which capitalist nations compete to plunder the natural resources, cheap labour and markets of the former workers’ republics.

Is it any wonder that workers in the former socialist bloc are starting to see through the anticommunist propaganda with which they have been bombarded for years? Is it any wonder that the name of Josef Stalin is once more being associated with freedom, dignity and social justice?

We look forward to the day when the workers of eastern Europe are able to recover from the stunning blow that was dealt them by the collapse of revisionism and the capitalist counter-revolution, restoring and rebuilding a socialist society even better than the one they had before.

Stalin was a thousand times right when he predicted: “I know that after my death a pile of rubbish will be heaped on my grave, but the wind of history will sooner or later sweep it away without mercy.” (1943, quoted in Felix Chuev, Molotov Remembers, 1991)

The socialist genie is out of the bottle and will not be put back; the workers will not be kept down forever. Whatever its twists and turns, history has a way of moving forward; a temporary defeat is not the end of the road but merely a dip in the long march of humanity towards communist freedom. We have no doubt that the workers of Europe and the world will ultimately build socialist societies that empower them to develop their talents, harnessing their collective labour and the fruits of the earth to rationally plan a bright, hopeful and sustainable way of life for humanity.