It might be asked why we should have any particular interest in the conduct of the class struggle in Transcaucasia that was carried out by the Bolsheviks. Beyond the fact that JV Stalin is known to have been a Georgian, little is known amongst our comrades about the history of the region.

Generally speaking, our comrades know the story of 1917 in the setting of Petrograd and Moscow. With the consolidation of power by the Khrushchevite revisionists at the 20th party congress, a concerted effort was made to rewrite the history of Bolshevism.

At that congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in 1956, the Armenian revisionist Anastas Mikoyan said during his report:

“Until quite recently we circulated and even held up as indisputable models books on the history of such big party organisations as the Transcaucasian and Baku organisations, in which the facts were juggled, some [persons] being arbitrarily glorified, while others were not mentioned at all.”

Of course, the person to whom Mikoyan objected to being ‘glorified’ was none other than JV Stalin, whom Mikoyan had himself publicly glorified for many years. Those whom Comrade Mikoyan thought had received insufficient praise is anybody’s guess, but you probably need to look no further than Comrade Mikoyan himself.

This article attempts to resurrect a little of the history of the Bolsheviks in Transcaucasia from the works of three Transcaucasian writers; Josef Stalin, Lavrentiy Beria and GN Doidjashvili.

Bolsheviks in the tsarist empire

The struggle waged by Stalin and the Bolsheviks of this region is important as an example of the Bolshevik work in Russia’s colonies, amongst the oppressed peoples of the Russian empire. Great significance lies in the fact that it was JV Stalin, a Georgian, who elaborated upon the basic Marxist teaching on the national question, and gave the famous definition of nation:

“A nation is a historically evolved, stable community of language, territory, economic life, and psychological make-up manifested in a community of culture.” (Marxism and the National Question, 1913)

The principal towns in which the class struggle was conducted in Transcaucasia were Batumi and Tblisi (in modern-day Georgia) and Baku (Azerbaijan). Additionally, Yerevan in Armenia and various small towns in Abkhazia, Ossetia and other places in the Caucasus witnessed fierce national and class struggle in the period from 1900-36. 1936 brought about the complete victory of the national policy of the Bolsheviks with the introduction of the Stalin Constitution.

Of the three proletarian centres, Tblisi was always the sleepiest. In an early estimate of the class composition of the town by Stalin, he remarked upon the fact that the proletarians there numbered only a few thousand, of whom the railway workers were the best.

Outside of these large cities the area was inhabited by a variety of backward peoples, many of them mountain peoples, some of whom had no written form of their language until the Soviet revolution brought in linguists to create one.

These peoples had been granted various rights over one another, which had set off one section against another – rights that were granted by the landlords and feudal princes. These petty privileges sustained animosity and hatred that caused the Bolsheviks and the Red Army many problems in the struggle to unify the workers and peasants in the fight for Soviet power during the civil war.

Baku, Tblisi and Batumi were linked in the late nineteenth century by the Transcaucasian railroad, and the oil pipeline from Baku stretched all the way to Batumi by 1900. This entire area began to grow and develop at a rapid rate in the nineteenth century as a result of the industrialisation of Russia and her colonies.

In 1846, the world’s first mechanically-drilled oil well was sunk in Bibi-Heybat on the outskirts of Baku. It was principally in Baku, therefore, that Stalin and his comrades built up the Bolshevik party, and that city provided many great revolutionaries and future leaders of the USSR.

Amongst the 26 Baku commissars who perished at the hands of reactionaries aided by the British during the civil war, there was only one survivor, Anastas Mikoyan.

The history of the Bolshevik revolution is inextricably bound up with the lives of the colonial peoples of the Russian empire – its victories, its defeats, its setbacks and its betrayals. The success of the national policy of Lenin and Stalin was a guarantee of the lasting victory of the proletarian revolution; it is not for nothing that Stalin remarked:

“Friendship among the peoples of the USSR is a great and important achievement. For as long as this friendship exists, the peoples of our country will be free and invincible.” (JV Stalin, Marxism and the National and Colonial Question, 1934)

Transcaucasia before 1900 – the three dassys

The origins of revolutionary social democracy in Transcaucasia can be found in three nationalist organisations that took shape in the latter half of the nineteenth century in Georgia, and especially in Tblisi, which was the centre of Transcaucasia; these groups were known as the ‘dassys’ (groups).

The ‘Pirveli’ dassy (literally meaning ‘first group’) was the product of the labours of a famous Georgian writer and poet named Ilya Chavchavadze (1837-1907). This group represented a feudal-progressive trend in Georgia and worked for the capitalist development and renaissance of Georgia.

The group defended the ‘Georgian nation’ and its language from attack by the tsar and his programme of ‘Russification’ in the mid to late-nineteenth century. In this way, the group played a progressive role, although its programme aimed for collaboration between the big landed estates, convinced that the liberal nobles could lead the capitalist development of Georgia.

A group of bourgeois intellectuals influenced by the Pirveli dassy began to publish the newspaper Droyeba (1866–86) and the journals Mnatobi (1869-72) and Krebuli (1871-73). This group was led in the main by Giorgi Tsereteli (1842-1900) and became known as the ‘Meori’ dassy (literally ‘second group’).

This group went further than the Pirveli generation, initially preaching bourgeois nationalism and republicanism. It stood for the capitalist development of Georgia’s national economy, although by the end of the nineteenth century it envisaged that its programme could be realised by supporting the big bourgeoisie and Russian tsardom.

As this process of intellectual exploration proceeded in Georgia, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels had been busy on the other side of Europe laying the foundations of scientific socialism and organising the First and Second Internationals.

By the early 1890s, Marxist ideas began to find their way into Georgia through two channels. Firstly, a number of exiled Russian social democrats brought their politics with them into exile. Secondly, there was the return to Georgia of a generation of intellectuals who had been abroad, principally for education or business.

These intellectuals actually saw their ‘Marxism’ as a constituent part of their enlightened ‘Europeanism’. As Noah Jordania (future Menshevik) said: “To be a Georgian and a European is the new motto.” (N Zhordania, Iberia and nationality, 1897)

In Europe, they had been exposed to social-democratic ideas, and many of the individuals who returned came to be known as ‘legal Marxists’, since the Marxism with which they returned was of the Fabian variety.

This process led to the formation around 1893 of the Messameh dassy (‘third group’), and the group around Noah Jordania became the main exponent of ‘legal Marxism’. The leader of the Meori dassy, G Tsereteli, was responsible for the naming of the Messameh dassy.

In 1895, the newspaper of the Messameh dassy published a statement that revealed the (limited) extent to which Marxist ideas had permeated the group’s thinking, and the extent to which it was very far from working out a way forward:

“We say that

“1. During these 25-30 years a new era has begun in our lives. Its characteristic feature is manifest in special economic relations, which means commodity exchange, trade. Here the old master gives way to the new, money. Money destroys the old and builds the new; it divides the people into two parts; two classes arise – the rich and the poor. The old distinction of estates is a fiction. Exchange is brought about by the division of labour, by the production of commodities. The production of commodities is precisely capitalism in general.

“2. Capitalism has several stages or phases. The last stage of capitalism is large-scale production. We have entered this stage but are not yet entrenched.

“3. If the proletariat and the bourgeoisie in our country are not sufficiently defined, that does not mean that we have had neither the one nor the other. In so far as our big landowners grow rich through land incomes they are bourgeois. Add to them the manufacturer, the usurer, the merchant and others … Our proletariat is a mixed organism. The majority have small allotments which give them the mere title of property owners, but in reality they are proletarianised elements (Bogano). They are working people whose fate depends both on the commodity market and the labour market. They are on the way to complete proletarianisation.

“4. In our literature a new (third) group (‘dassy’) has arisen. This group (dassy) is the exact opposite of the old group (dassy), which has no basis. It is progressive, whereas the latter is retrogressive. So far the bourgeoisie does not have its own organisation in our literature, has no group (dassy) in it to express its interests, unless the reviews by Mr N Nikoladze in Moambeh are taken into consideration. The bourgeoisie functions in life. In so far as it destroys the old patriarchal system by its activity, it is progressive; in so far as it ruins the people, it is retrogressive. The motto of the new group (dassy) is: ‘Scientific investigation of the new trend of life, and struggle, not against its tendencies – that goes on without us – but against those consequences which demoralise the people.’ In this respect struggle means enlightening the oppressed and fighting for their interests. The enemy of this new trend is at the same time the enemy of the oppressed.

“This is our outlook upon the life in general and upon literature in particular.” (Kvali No 14, p.15, March 26 1895)

That the Messameh dassy recognised the class struggle in social development is clear. However, the Messameh dassy in general, and a number of groupings within it, never carried the Marxist understanding of class struggle to its conclusion.

Noah Jordania, who later became Menshevik president of ‘independent’ Georgia, consistently preached in favour of alliance between the proletariat and liberal bourgeoisie. He never broke with the ideological constraints of the previous dassyist groups and fought against recognition of the proletarian dictatorship.

This ideological position he carried over into open hostilities in his later years, when he worked against Soviet power and eventually became a paid hireling of the imperialists, much like many of his fellow Mensheviks.

The seeds of his future degeneration, as with other Mensheviks and opportunists such as Trotsky, Kamenev, Zinoviev and Bukharin, can be found in the incorrect ideological positions that he took up in the early 1900s, which only Lenin and the Bolsheviks were to prove capable of answering.

On the national question Jordania wrote: “A nation united materially is united ideologically also. Everyone strives to develop national labour, to strengthen the nation … The peasant and the worker are just as interested in the greatness of the nation as the bourgeois merchant.” (N Zhordania, Economic Development and Nationality, 1894)

Jordania was not talking here about the real patriotism of the working class; he only understood the national question from the point of view of the liberal bourgeoisie. In later years, Jordania and the Georgian Mensheviks turned what Stalin termed ‘defencist’ nationalism – the nationalism of the oppressed (colonial) countries as a reaction against their national subjugation – into an aggressive nationalism, and even organised pogroms and fratricide amongst the workers of the Caucasus.

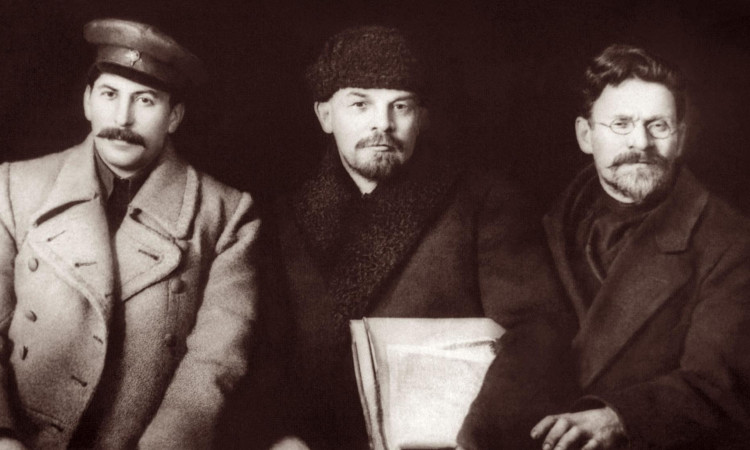

In 1897, the young revolutionary Lado Ketskhoveli joined the Messameh sassy. He gravitated towards the more revolutionary members of the group, principally Sasha Tsulukidze, who had joined in 1895. By 1898, the basis of a revolutionary leadership was completed with the recruitment of JV Stalin.

Lavrentiy Beria described the young Lado Ketskhoveli as follows: “The revolutionary activity of Comrade Lado Ketskhoveli began in 1893 in the Tiflis seminary from which he was expelled for the participation in a student ‘riot’. In order to continue his education he was compelled to move to Kiev in 1894.

“Between 1894 and 1896 Comrade L Ketskhoveli took an active part in the revolutionary Marxist circles of Kiev. In 1896 the police arrested him and after three months’ imprisonment he was sent to his birthplace (in Georgia) under police surveillance.” (L Beria, History of the Bolshevik Organisations of Transcaucasia, 1935)

Through Lado Ketskhoveli and progressives in Tblisi others in the legendary Tiflis seminary had been supplied with ‘illegal’ literature or came to attend study circles, and it was from the ranks of this seminary that Josef Stalin emerged. By 1898 the group of Stalin, Ketskhoveli and Tsulukidze comprised a young, revolutionary minority in the Messameh dassy.

Stalin and the minority within the Messameh dassy

Two conflicts broke out within the Messameh dassy soon after the emergence of the minority group under Stalin’s leadership. Firstly, the majority within the Messameh dassy were happy to limit the work of the group to the legal propagation of Marxist ideas in Kvali, a ‘legal’ paper, and to continue their work inside study circles away from open conflict with tsardom.

Stalin, Tsulukidze, Ketskhoveli and others held that an illegal press was highly important for the continuing spread of openly revolutionary propaganda amongst the workers, and for the organisation of a truly proletarian party, which alone could conduct the struggle against the autocracy.

In 1900, exiled Russian revolutionary Victor Kurnatovsky arrived in Georgia. He was a close collaborator of Lenin’s from the Emancipation of Labour group, and a follower of the newly published Iskra. Kurnatovsky added his considerable influence to the minority viewpoint, and the question of developing the work from study circles to the leadership of the mass struggle against the autocracy brought the minority within Messameh dassy into conflict with Noah Jordania.

These differences became more pronounced after the second congress of the Russian Sosial-Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP, forerunner of the communist party) and eventually became differences of principle between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks.

When Lenin published his pamphlet What Is To Be Done? in 1901, he recalled how a mere description of conditions inside the factories was no longer sufficient; the time had now come to lead the mass struggle. The Georgian Bolsheviks were working in line with the thinking of Lenin and were advancing along the course that Lenin was charting.

Stalin and his comrades threw themselves into the work of winning over the study circles in their region to this viewpoint. With the help of Kalinin, Alliluyev, Franceschi and others, the minority group won considerable influence.

Stalin personally conducted more than five Georgian or Russian-language study groups around Tblisi at this time, and at least an additional six inside local tobacco, boot and vegetable oil factories, as well as inside the Mirzoyev weaving mill.

Speaking in 1926 to the railway workers of Tblisi, Stalin recalled these busy days when he too was a student: “Comrades, permit me first of all to tender my comradely thanks for the greetings conveyed to me here by the representatives of the workers.

“I must say in all conscience, comrades, that I do not deserve a good half of the flattering things that have been said here about me. I am, it appears, a hero of the October Revolution, the leader of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the leader of the Communist International, a legendary warrior-knight and all the rest of it.

“That is absurd, comrades, and quite unnecessary exaggeration. It is the sort of thing that is usually said at the graveside of a departed revolutionary. But I have no intention of dying yet.

“I must therefore give a true picture of what I was formerly, and to whom I owe my present position in our party.

“Comrade Arakel said here that in the old days he regarded himself as one of my teachers, and myself as his pupil. That is perfectly true, comrades. I really was, and still am, one of the pupils of the advanced workers of the Tiflis railway workshops,

”Let me turn back to the past.

“I recall the year 1898, when I was first put in charge of a study circle of workers from the railway workshops. That was some twenty-eight years ago. I recall the days when in the home of Comrade Sturua, and in the presence of Djibladze (he was also one of my teachers at that time), Chodrishvili, Chkheidze, Bochorishvili, Ninua and other advanced workers of Tiflis, I received my first lessons in practical work.

“Compared with these comrades, I was then quite a young man. I may have been a little better-read than many of them were, but as a practical worker I was unquestionably a novice in those days. It was here, among these comrades, that I received my first baptism in the revolutionary struggle. It was here, among these comrades, that I became an apprentice in the art of revolution. As you see, my first teachers were Tiflis workers.

“Permit me to tender them my sincere comradely thanks.” (Reply to the greetings of the workers of the chief railway workshops in Tiflis, 8 June 1926)

As Stalin and the minority group increased their influence, they began to help organise and lead strikes amongst the workers in the railway depots, where conditions were cruel. Sergei Alliluyev (whose daughter Stalin later married) was a worker in the railway depot at this time, and described the conditions in the works and the Bolshevik agitation there:

“July of that year [1900] was intolerably hot. The air in the workshops was stifling. Dazed men could barely walk across the shop floors, exhausted from overwork, from the stench and from the heat. Everyone wanted to finish his work and escape from this hell.

“When the siren finally sounded its harsh clamour, workmen sighed with relief. But this was often premature. The siren had barely begun its shaking wail, when the foreman would announce: ‘Keep the machines running. We are doing overtime!’ The siren would come to an abrupt stop, but the electric transmitters continued humming in the workshops.

“Overtime was a frequent occurrence. In some workshops a number of men stood for as long as 18 hours at the work benches. At first the opportunity to earn extra money was welcomed. But as the overtime system spread, so pay became smaller and smaller.

“In the last ten years, wages decreased by about 40 to 50 percent. If in the nineties turners and fitters received a rouble and a half for a day’s work, now they received a rouble for a full day’s work, plus two to three hours’ overtime.

“The turners working on carriage wheels received 60 kopecks a day. To secure a minimum living wage, every workman had to put in 50 working days a month. In other words, one had to stay for a further five or six hours at overtime. Some men did not leave the workshops for weeks on end and slept beside their machines.

“The plight of the unskilled labourers was even worse.

“By July the workers, driven by need and despair, demanded higher rates of pay and the abolition of overtime. Not everyone understood the need for this. Some were afraid that the management would stop overtime, but leave their wages at the existing level. We had to explain to them that overtime led to ill health, increased the number of unemployed, and lowered the daily wage rate.

“Whilst this was apparent to leading workers, the older, less educated men, with large families, remained unconvinced. No amount of propaganda could convince them. As a result, a number of fights flared up, of a totally unforeseen nature. The more militant among the younger workers beat up some of the older men.

“Things then came to a head at the end of July, and several mass meetings were held at night in the nearby hills. At one of the meetings attended by the lathe operators, Mikhail Kalinin appeared. The question of a strike was discussed. Kalinin talked about the difficulties this would entail, particularly for workers with large families.

“‘We must face facts.’ He said. ‘While we are getting ready to strike, the police are not slumbering, either. They might make a few arrests to sow confusion in our ranks. Are we ready to meet this challenge?’ But before he could answer his own question a dozen men replied in friendly unison: ‘We are ready!’

“‘Yes, we are ready,’ Kalinin continued decisively. Nothing can frighten us, and nothing will. We social democrats know that every struggle demands sacrifices, and that our struggle is for the cause of the working classes, the producers; it is a holy struggle.’

“The preparations for the strike were undertaken by the revolutionary social democrats in the face of the opposition of the majority of the Messame dassy, which tried to break the strike. Soso Djugashvilli [JV Stalin], Ivan Luzin and Mikhail Kalinin encouraged this open struggle among the workers.” (Citation)

The efforts of the minority began to pay off. Despite some setbacks, including the imprisonment and eviction of Sergei Alliluyev and his family, the minority around Stalin began to grow into the embryo of a Bolshevik organisation.

On May Day in 1900 a rally of some 500 workers was organised in the foothills outside Tblisi, and the following year saw the first public May Day demonstration end in bloodshed as many more rallied to the call of the Messameh dassy minority.

To organise this event, the minority group prepared a number of leaflets, and its members took part in strike action and demonstrations in the build-up.

A demonstration of striking Tblisi factory workers on 22 April saw a fierce battle with the Cossacks and police. Fourteen workers were injured and 50 arrested.

Writing in Iskra, Lenin declared: “The event that took place on Sunday 22 April in Tiflis is of historic import for the entire Caucasus: this day marks the beginning of an open revolutionary movement in the Caucasus.” (July 1901, cited in L Beria, History of the Bolshevik Organisations of Transcaucasia, 1949)

Before the temperatures had time to cool, the minority group issued more leaflets and brought more workers out for the 1 May holiday.

One of the leaflets issued by the minority group declared: “The workers of the whole of Russia have decided to celebrate the First of May openly – in the best thoroughfares of the city. They have proudly declared to the authorities that Cossack whips and sabres, torture by the police and the gendarmerie hold no terrors for them.

“Then friends, let us join our Russian comrades! Let us join hands, Georgians, Russians, Armenians; let us gather, raise the scarlet banner and celebrate our only holiday – the First of May!” (Central Archive Board, Georgian SSR, Folio 158, File no 355, 1901, leaf 47, quoted in L Beria, ibid)

The culmination of this work was the appearance in September 1901 of the first issue of Brdzola (The Struggle). By November 1901, on Stalin’s initiative, the first Tblisi conference of the social-democratic organisations was held, with 25 delegates in attendance.

This conference elected the first Tblisi committee of the RSDLP, which followed the line of Lenin’s Iskra. The committee set about in an organised fashion to disperse certain comrades to undertake revolutionary work across Transcaucasia. Following the demonstrations of April and May 1901, and the establishment of Brdzola, Stalin was now ‘underground’ and he left Tblisi on party work.

JV Stalin’s revolutionary activities in the period up to October 1917 include a great many adventures, arrests and exiles. His life mirrors closely the life of all the great Bolshevik revolutionaries of the period. These adventures are far too numerous to be dealt with here, as is the complete history of the February revolution and the role played by the Mensheviks.

For our purposes, having set out the origins of the Bolshevik and Menshevik groups in Transcaucasia, and having indicated the origins of the national chauvinists and national deviators, it will be enough to give a cursory picture of the situation of the national minorities in the period 1900-17 through the words of General Vorontsov-Dashkov, and then to proceed with the story of the Mensheviks and Bolsheviks in the period after October 1917 in Transcaucasia.

Class struggle in Transcaucasia 1900-17

In 1907, General Vorontsov-Dashkov, the viceroy of the Caucasus, wrote in great alarm to the tsar, Nicholas II:

“At the time of my arrival in the region, the revolutionary movement, evidently connected with the movement throughout the empire [ie, the revolution of 1905-07] had already assumed dimensions that were dangerous to the state. I immediately declared martial law in Tiflis …

“At the same time, part of the Tiflis gubernia [governorate], and the whole of the Kutais gubernia, were swept by revolts of the rural population; these revolts were accompanied by the wrecking of landlords’ mansions, the refusal of the peasants to pay taxes, their refusal to recognise their rural authorities, the forcible seizure of private land and the wholesale felling of trees in state and private woods …

“In Tiflis, Baku and other towns in the region, strikes of workers in all trades, including domestic servants, were a daily occurrence.”

What was at the bottom of these numerous and widespread peasant revolts in Georgia? General Voronstov-Dashkov, who cannot be suspected of having had any sympathy for the Georgian people, provided the answer to this question. He wrote:

“In Transcaucasia, and particularly in Georgia, the serfs were emancipated on terms that were particularly advantageous for the landlords and disadvantageous for the peasants … moreover, the peasants’ obligations to the landlords became more onerous than they were under serfdom …

“The state taxes are collected by fair means or foul. If any trees grow on the peasants’ lots, those lots immediately come under the forest tax; if another part of the lot is covered with water owing to a river changing its course, it comes under the fishing tax … Things have reached such a state that walnut trees, planted and reared by the peasants themselves, on their own land, come under the tax.”

Three-quarters of the total area of land in Georgia belonged to the big landlords, the church and the state, and only one-quarter belonged to the peasants. In some gubernias, Tiflis and Kutais for example, 90 percent of the land belonged to the state.

About half the total peasants in pre-revolutionary Georgia owned less than two-and-a-half acres of land per family; only one in 15 peasant households owned a plough, and only one in three or four owned a mattock [similar to a pick-axe] or other hand tool.

This economic oppression was still further intensified by political and moral oppression. Out of the state budget for Georgia, which amounted to 4.7m roubles, the tsarist government allocated 57 percent to the maintenance of the police force, and only 4 percent to public education.

Exposing the policy pursued by the tsarist government in the border regions of the Russian empire, Josef Stalin wrote in 1920:

“Tsarism deliberately settled the best areas in the border regions with colonisers in order to force the natives into the worst areas and to intensify national enmity. Tsarism restricted, and at times simply suppressed, the native schools, theatres and educational institutions in order to keep the masses in intellectual darkness.

“Tsarism frustrated the initiative of the best members of the native population. Lastly, tsarism suppressed all activity on the part of the masses of the border regions.” (JV Stalin, Marxism and the National and Colonial Question)

To be continued.