On 13 February 2020, the government of Venezuela – the legitimate Bolivarian government led by President Nicolás Maduro – made a request to the International Criminal Court (ICC) to investigate the US government for crimes against the Venezuelan people committed through the method of ‘sanctions’ – the genocidal economic blockade and other coercive measures that have been used to try to force both government and people to toe the line of imperialist diktat.

Countries that have the determination and resolve to resist imperialism – ie, Cuba, Iran, Syria, Venezuela, north Korea (DPRK) – resist imperialist sanctions through diplomatic methods if possible or military force if necessary. Part of the diplomatic route entails making appeals to international bodies such as the United Nations (UN) and the ICC in the hopes of alleviating the socioeconomically destructive effects of sanctions without firing a single shot.

This is, after all, the official philosophy central to the existence of such international institutions, whether governmental or non-governmental: to mediate international conflicts in a way that minimises interstate violence and maximises the wellbeing of all nations equally.

Officially, the International Criminal Court (ICC) was established to investigate crimes committed by state or non-state actors such as genocide, war crimes, crimes of aggression and crimes against humanity. The ICC also claims jurisdiction over prosecuting individuals convicted of such crimes.

In practice, it is clear they do not such thing. The greatest crimes of our times have gone entirely unpunished, their perpetrators not only walking free but handsomely rewarded. If the ICC functioned as advertised, we would surely have seen the likes of George W Bush, Tony Blair, Hillary Clinton, Benjamin Netanyahu, etc tried for their atrocities in the middle east and elsewhere.

The idealistic lens through which we are taught to view ‘international institutions’ such as the ICC and the UN encourages workers to blame ‘rogue states’ (ie, those who stand up to imperialism) for abandoning such diplomatic avenues, and blinds us to how such institutions work in practice.

A recent example of a state being deprived of a diplomatic avenue is Iran’s failed appeal to the UN to punish the US’s illegal assassination of General Qasem Soleimani. Iran’s representative wasn’t even allowed onto US soil, never mind being admitted into the UN general assembly building in New York.

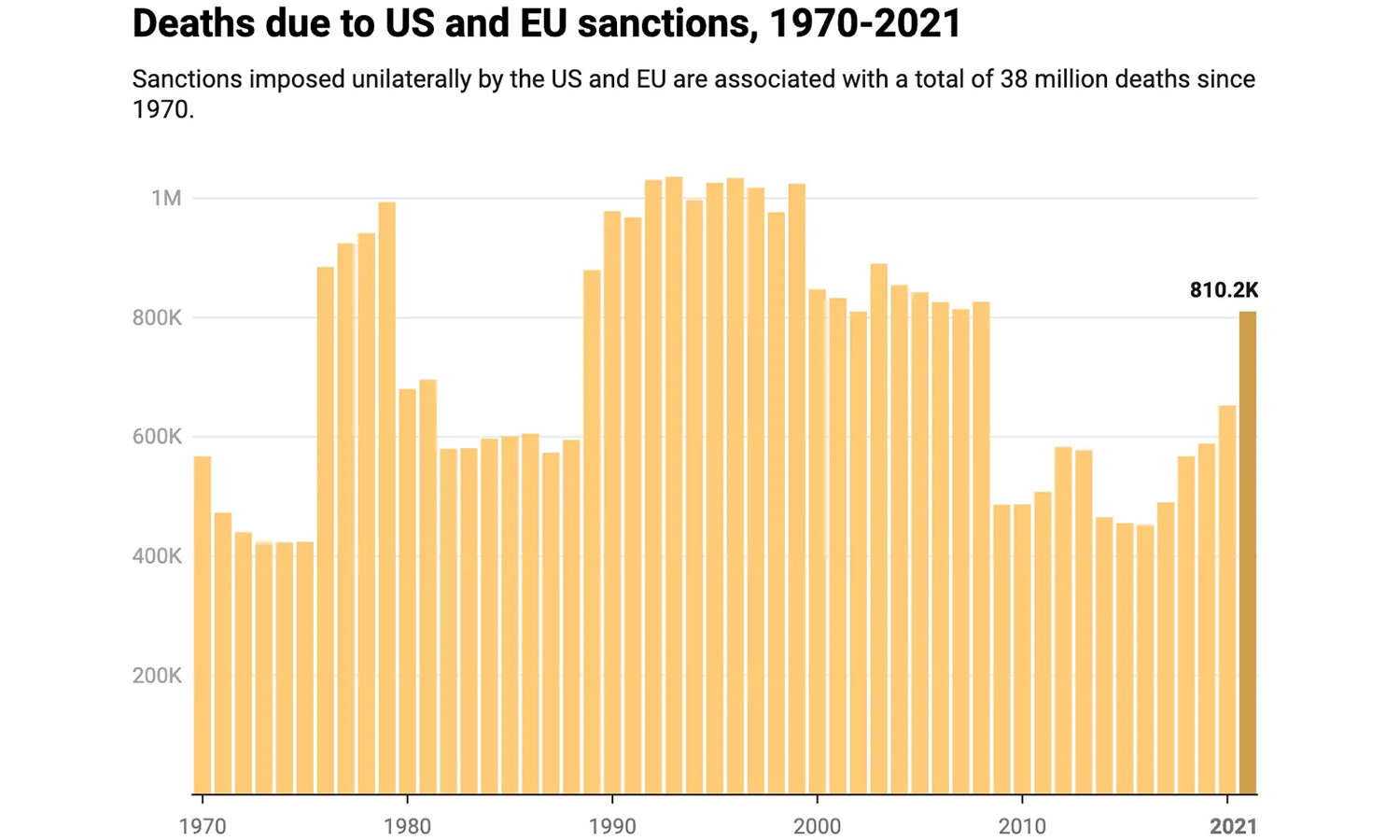

Knowing all this, Venezuela, wishing to prove to the world its commitment to maintaining global peace, has made the honourable attempt to present its case to the ICC. After all, sanctions are an instrument of genocide (enforcing famine, as is bitterly remembered by Iraq and the DPRK); they are clearly an act of economic aggression that the international community should not tolerate. The resulting radical impoverishment of the country is truly a crime against humanity.

Venezuela has from the start demonstrated its faith in the ICC, and was amongst the first to sign the Rome Statute in 1998 recognising the court’s authority. The US, by contrast, not only refused to sign up, but passed a bill giving its military officials total immunity from any liability of prosecution by the ICC.

Whilst several countries bowed to US pressure and agreed to this exceptionalist immunity, Venezuela stuck by its guns and refused.

Imperialism in the dock

Venezuela classes US sanctions against its people as ‘unilateral coercive measures’ (UCM). Such measures, it argues, constitute a crime against humanity, for they meet the enumerated criteria:

a) “an attack” (non-military). An attack is a course of conduct that implies the commission of multiple acts referenced in article 7, paragraph 1, of the statute;

b) “generalised or systematic”. It is not necessarily directed against a specific group and is spread over time;

c) “against a civilian population”;

d) “in conformity with the policy of a state or organisation” (as adopted by the United States government through laws, executive orders and decisions, regulations, threats and other diverse actions).

The ICC prosecutor representing Venezuela’s case divides it into two constituent parts:

“a) The Facts: This part details the situation in Venezuela before the application of unilateral coercive measures by the United States government. Moreover, it describes the impact that UCMs have had on the Venezuelan economy [depriving it of $116bn – the equivalent of six years’ national budget], the Venezuelan people’s enjoyment of human rights, and the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela’s right to development.”

In the document presented to the ICC, Venezuela relates a group of cases and facts that have impacted the Venezuelan population, such as the increase in infant and adult mortality, the increase in disease, the reduction in caloric intake, the contraction in food imports, and the impact on public services such as education, potable water, electric service and transport. All are attributable to the unilateral coercive measures and other threats imposed on Venezuela.

The lawsuit includes cases of patient deaths in the country and abroad as a result of the high cost of treatment for patients with kidney disease, bone marrow transplants and liver transplants, that could not be paid by the government of Venezuela owing to the blocking of its bank accounts and resources in the international financial system.

“b) The Law: This part argues that UCMs are illegal, details the crimes committed by their application and develops the judicial and admissibility aspects for the ICC.”

On the face of it, this is a solid case, but there is one fatal problem: since the US never ratified the Rome Statute, it is not a member state of the ICC. Now, the ICC still has room to prosecute under ‘jurisdiction of effects’, meaning that although the US is not a member state of the ICC, the criminal actions of the US as a state directly affect the wellbeing of an ICC member state, Venezuela.

Therefore, the ICC can investigate this case and pass judgement on US authorities.

The US’s refusal to ratify the Rome Statute, whilst maintaining its grip over the UN, is a strong indicator that the US’s ‘commitment to international law’ is entirely conditional to its imperialist interests. To paraphrase Comrade Lenin: imperialism doesn’t seek democracy, justice or liberty – it seeks domination.

Although the Venezuelan government may not expect to make many immediate tangible gains through this appeal, it will at least serve to draw a line in the sand and hold imperialism to account before the court of public opinion, winning over potential sympathisers to the anti-imperialist struggle.

Meanwhile, the coronavirus is opening the eyes of many workers to the total unfitness of the present system to respond to such emergencies in a way that meets their needs.

Not least amongst the lessons to be learned is the way the imperialists have taken the opportunity not to deliver aid but to tighten sanctions on countries like Iran and Venezuela – in the full knowledge that by doing so they are pushing already overburdened health systems to breaking point and condemning thousands of innocent civilians and medics to an early grave.

As with all such sanctions, the imperialists work on the assumption that if they can induce enough suffering and bring about a high enough death toll, this will undermine the moral of previously steadfast populations and turn them against their own governments, thus creating a force for their overthrow from within.

Their barbarous calculations are likely to backfire, however, not only strengthening the resolve to resist from within, but also serving to open the eyes of workers at home to the truly inhuman nature of the capitalist-imperialist system of production for profit.