At some point during late September 2020, a 19-year-old woman who was collecting animal fodder with her mother in the village of Hathras, Uttar Pradesh, was grabbed and dragged by the dupatta (scarf) around her neck into an adjoining field by four men and was there brutally gang-raped and beaten. Her treatment was so vicious at their hands that she was left with terrible injuries to her neck and spine.

Nobody can name this woman or give exact details of the time because the police initially blocked off her family and the village they live in from the press and anyone else. Neither the family nor the victim can be named as we go to press, and even members of the opposition Congress party are not allowed to approach them. This in a country that the Indian government would have us believe is the ‘largest democracy in the world’.

We do know that the young woman was taken by her brother to a police station somewhere in India’s most populous state of Uttar Pradesh to report the attack, but police officers there refused even to register a first information report. The badly wounded teenager, who was a member of the lowest caste – a dalit – was admitted to the Jawaharlal Nehru medical college in Aligarh, but upon her condition worsening she was moved on 28 September to Safdarjung hospital in Delhi, where she died the next day.

While in hospital, she gave a filmed statement about her attack – a dying testament, in which she described the attack and named her four attackers, all members of the thakur or highest caste in the officially banned (since 1955) hindu caste system. The four men have since been arrested and five policemen from the police station in charge of the case have been suspended for dereliction of duty.

On 30 September, in an extreme case of ‘adding insult to injury’, the police brought the young woman’s body to her home village, which was still cordoned off, and, without the consent of her family, cremated her remains in the middle of the night in an open field having barricading the victim’s family into their home.

Hindu ritual dictates that cremation should take place in the morning following preparation of the body by the family. Even in death, this unfortunate young woman and her family were cruelly mistreated and mocked by the powers that be.

Prashant Kumar, the additional director general of law and order in Uttar Pradesh, has claimed that the victim’s family had given consent to the cremation, which, he says, was only held at night to avoid any potential threat to order in the area.

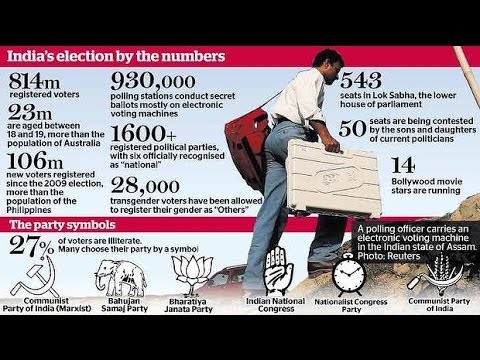

The state government of Uttar Pradesh is run by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) through its chief minister, Yogi Adityanath, an extremely backward and religious extremist hindu monk. Under pressure both nationally and internationally for its botched (if we are being kind) handling of the rape and killing of this young woman, the Uttar Pradesh government has labelled the criticism as an “internationally hatched plot”, claiming that it has been organised in order to defame the state government, which has now ordered a probe.

A routine event

Meanwhile, life in the state goes on as usual. It was reported a 22-year-old dalit woman was raped and killed in the state’s Balrampur district on 29 September. She too was cremated in the early hours of 30 September by the police without her family.

Around 20 percent of the roughly 200 million people who live in Uttar Pradesh are dalits – people who were once referred to as the ‘untouchables’, forming the lowest rung of India’s hierarchical caste system. Dalit women are mainly landless labourers or scavengers.

According to an Indian National Crime Records Bureau report, 3,500 dalit women were raped across the country last year. More than 500 dalit women were sexually assaulted in Uttar Pradesh alone.

It is mainly because this 19-year-old young woman ended up in Safdarjung hospital in Delhi just before her death that her case came to public attention, and was followed by both national and international demonstrations highlighting the oppression of Indian women in general and dalit women in particular. It is sad but not altogether unexpected that in Uttar Pradesh there was a small counter-demonstration of thakur caste members claiming that they are being unfairly accused.

According to official figures, ten dalit women were raped every day in India last year. The northern state of Uttar Pradesh has the highest number both of cases of violence against women and of sexual assault against girls. Three states – Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Rajasthan – report more than half of the cases of atrocities against dalits. These figures are, of course, based solely on cases reported; there is no way of estimating how many go unreported.

A 2006 study of 500 dalit women in just four states across India showed that 54 percent had been physically assaulted and 46 percent had been sexually harassed. There is little to suggest that things have improved significantly since then.

Anuradha Banerjee, a professor at Jawaharlal Nehru university, says that women and girls in India have traditionally suffered on account of gender and other inequalities, pointing out: “In the case of dalit women, they suffer triple oppression of caste, class and gender.”

This last point is important if we are to understand increased oppression of dalits in general and dalit women in particular. Or, to be more exact, one part of that last point – ie, class.

As India moves at great velocity towards becoming a fully-fledged mass producer of commodities for worldwide consumption, the ruling circles both domestic and foreign have no need for some of the old, feudal divisions that previously controlled the Indian people’s lives. Some of those who were born into higher castes now find themselves standing behind their low-caste brethren in the queue to be exploited in factories, mines and mills, and some of the rage they may feel at this new turn of events is undoubtedly being aimed with greater venom at those they have been taught to believe are their inferiors.

As capitalism smashes the remnants of feudal relations in India and moulds the majority of people into exploited proletarians, it is hoped that they will cast off their old prejudices and stand together to face their real enemy – the exploiting capitalist class – in a spirit of class solidarity.

______________________________

Read The First Indian War of Independence (1857-58) by Karl Marx.