A new Saturday, a new early morning, a new trip out of Moscow. Another light breakfast anywhere between the bus and the metro, and a new station to arrive at and from which to depart for a new destination … Dubosekovo.

Volokolamsk is a city located 129km north-west of Moscow. My destination, 8km before. A small stop on the Moscow-Riga railway line. Dubosekovo serves a village with a current population of 140.

At the age of 13, my father invited me to read a novel written by K Simonov entitled The Battle of Moscow. For me, it was a novel full of adventures; a novel in which some men fought by conviction to exhaustion; in which normal people did unheard of things; a novel starring a group of friends, in which they suffered, but in the end the protagonists defeated evil.

It was a novel that narrated events that had occurred in this place on 16 November 1941. This was a book that taught me that sometimes reality becomes a novel.

During ‘Operation Typhoon’, the German forces extended the front in pincer fashion in an attempt to surround the capital, delivering strong blows from south-east to north-west. The very powerful German army had allocated 60 percent of its best resources to this operation.

At 6.00am on 15 November 1941, the central army of the Wehrmacht began the decisive blow. The fourth Waffen SS Panzer group, commanded by General Erich Hoepner, attacked the flank of the Soviet troops on the Volokolamsk road, to pave the way for the fifth army corps. The purpose was to fulfil directives recently issued by Hitler: encircle Moscow as soon as possible, force the surviving population of the bombings to flee or die of hunger, and later take the city. After which there was a specific order to dynamite the Kremlin.

In these clashes, the 316th infantry division of the 1,075th regiment under the command of Major General Ivan Vasilievich Panfilov was cut off at Dubosekovo station and had to face the second division of the SS Panzer group.

The 316th division, integrated into the sixteenth army under the command of General KK Rokossovsky, had been transferred from Kazakhstan to Moscow and was made up of men of different ethnicities. This multiculturalism is the historical inheritance of the country, and it was represented at all levels in the Soviet army.

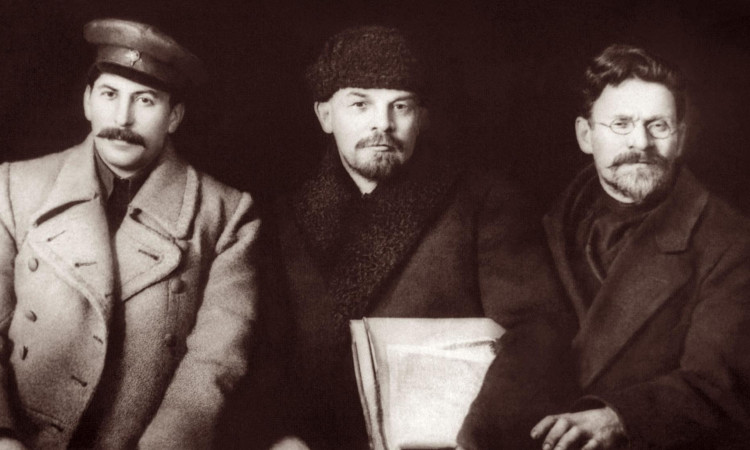

Together with the ‘giants’, 2017

The greatest recognition of the fierce fighting that took place here were the words of Erich Hoepner himself, who in an official report defined the 316th division as: “a savage division, whose soldiers do not surrender, are extremely fanatical and do not fear death”.

Major General Panfilov was admired by his men: his words and the ways in which he treated the men had earned him the affectionate nickname of ‘Father General’ (генерал Батя), and this admiration resulted in massive heroism.

Before the hard fight, the words of MI Kutuzov in Borodino, “Moscow is behind us”, were recalled in the speech of the political instructor VG Klotchkov, barely 30 years old, who, paraphrasing the Marshal, said: “Great is Russia but there is nowhere to retreat, Moscow is behind us”.

When he came out of the trenches with a handful of grenades running towards the tanks, the soldiers of the 1,075th infantry regiment followed him … After heavy fighting, the isolated group of 28 men repelled a new attack of SS tanks that tried to break the lines …

At 7.00am on 16 November, the remains of 18 tanks were left on the field. The rest of the Panzer division began to fall back. General Panfilov died two days later from wounds he sustained.

This feat was reported in all the newspapers, with the intention of raising the fighting spirit of all the people. Novels were written, songs were composed; it is one of the most widespread feats of the Battle of Moscow.

In this war, propaganda played a major role. It was part of what is known as ‘psychological warfare’ and was used to raise the morale of some and undermine that of others. Heroic deeds became legendary.

The arguments about whether there were 28 or 50 men who fought here, or whether the tanks destroyed were 14 or 20 in number do not matter. The important thing is that these facts showed that German tanks could be destroyed. And, for the first time in the war, a Panzer division started to retreat.

A few days later, on 6 December, Marshal Zhukov began the counteroffensive. For the first time since June 1941, with the front strengthened by the arrival of Siberian troops, and with new weaponry such as the T-34 tanks and Katyusha rocket launchers, it was possible to initiate an attack, rather than just carrying out defensive tactical operations. By 7 January 1942, the Nazi troops had retreated 250km.

The Battle of Moscow was the first battle lost by the Reich to any European army. The legend of the invincibility of Hitler’s armies was shattered at the gates of Moscow. According to German historians, the casualties of the German army in Operation Typhoon amounted to 450,000 men.

The feat of the 28 is remembered in an old song that became Moscow’s anthem in 1995. “Let us remember that harsh autumn, the noise of the tanks and the gleam of the bayonets. In our hearts the 28 will live, the best of your children. The enemy will never get you to bow your head. My dear capital, my golden Moscow.”

Today, from the small Dubosekovo station, I walk along the Volokolamsk highway. Just 300 metres away, on the north side of my path, there is a huge sculpture more than 30 metres high commemorating the feat of the 28.

At the feet of these huge men of different ethnic groups, colourful wreaths of flowers are placed. Some people are walking among these giants. Behind them, again, the immense plain stretches to the horizon, the view only broken by the birch trees that seem somehow to multiply this sculptural group.

On the other side of the road, the south side, a group of trenches are preserved that can be easily accessed with some explanatory plaques in between. A couple walks among them with their children of about 4 and 6 years old. The mother patiently reads the different plaques to them, talks to them about soldiers in a soft and calm voice.

Children play and jump between trenches as if they were swings. Their cheerful voices make me smile. I think of the very different use they are making of these corridors surrounded by dirt and with small protective spaces that serve as temporary hiding places for their parents.

A little one with a still wobbly walk on this stony ground laughs out loud when he finds his older brother in one of these holes and then keeps running after him. The older one climbs out of the trenches and jumps back inside under the watchful eye of his father. The other, like all younger brothers, tries to imitate the older one. His height does not allow him to climb alone.

It’s hot. The father takes off a light jacket that he is wearing. He keeps it in a backpack that he keeps on the floor while he takes out a bottle of water to give the little one a drink. The boy laughs as he jumps and climbs back up with his father’s help.

A white and blue striped t-shirt with wide straps exposes the father’s arms, arms that the child uses to play and swing. The older brother joins the group. At the second jump and speaking a few words that I cannot hear from where I am, the boy searches in his father’s backpack. When he stands up, I see that he is carrying a toy gun in his hand.

After a cry, between surprise and joy, the little one stops jumping and puts his hands in the same bag. He searches and loudly announces the great find that he has in his hands. The gun is too big for the boy’s hand but he grips it tightly.

With a delicate movement the father picks up the little boy and carries him to the southern end of the trench. There, at the peak of that earth shelter, he teaches him to protect himself while the boy aims at an imaginary enemy. The older brother, attentive to the father’s words, does the same. In the background, the birch trees watch over the children’s play.

I’ve been lucky with the weather. Another picnic and another magnificent summer day. I start the return to Moscow from the famous ‘Dubosekovo crossing’, where the railway line crosses the Volokolamsk highway – where men die and legends are born.

Following the Volokolamsk road, at a distance of approximately 1km from the monument, is the tomb honouring the 28 heroes. Major General Ivan Panfilov is buried in the Novodevichy cemetery convent in Moscow together with Lev Dovator (cavalry) and Viktor Talalijin in a monument dedicated to the ‘Heroes of Moscow’.