Read part one of this review.

Read part two.

*****

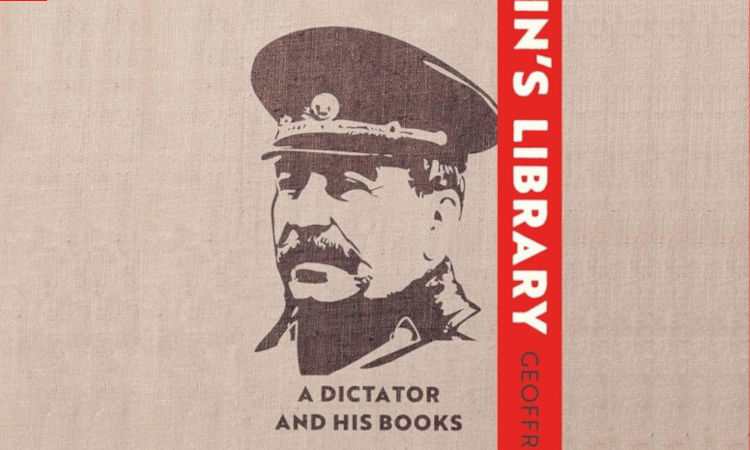

Josef Stalin is an obvious candidate for the most vitriolically abused world leader ever. And this for the simple reason that under his leadership private property and the market suffered unprecedented hammer blows. Under his stewardship, socialism spread to eastern and central Europe, China, the DPRK and Vietnam, taking this vast mass, along with the USSR, out of the world market.

Under his leadership, the USSR emerged victorious in the Great Patriotic War, frustrating imperialist plans for its defeat by the vile Nazi regime. No one has delivered such devastating blows to imperialism as did the USSR during the three decades of Stalin’s leadership.

This being the case, no one would expect imperialism’s representatives, its ideologues, to show any objectivity towards this undisputed and towering leader of the international communist movement for three decades of extraordinary difficulty and exceptional opportunity. With the onset of the cold war, aided by Nikita Khrushchev’s slanders against Stalin in his so-called secret report, imperialism had a field day – the so-called ‘left’, the Trotskyites and revisionists followed, as was to be expected, the imperialist lead in repeating all the filthy lies about Stalin.

But we are now witnessing a turn as people are able to compare the great achievements of the Soviet Union with what followed the collapse of the USSR and the people’s democracies of the eastern bloc, thanks to Khrushchevite betrayal.

Vast masses in present-day Russia and beyond compare the lives of degenerates like their former comprador president Boris Yeltsin with the heroic lives of selfless dedication to the cause of socialism led by JV Stalin and his close comrades, who inspired scores of millions of Soviet people to storm heaven and make miraculous achievements.

Many leaders at the time, Sergei Kirov, for instance, led a humble life devoted to the cause. Kirov was one of many who paid attention to the most minor problems in the daily lives of people; who genuinely believed in a bright socialist future and worked between 18 and 20 hours a day; who was a convinced communist and sang Stalin’s praises for strengthening the party and the USSR, and for the country’s strength and development.

“It’s the leadership group as a whole that demonstrates its work dedication and self-sacrifice,” writes Domenico Losurdo in his biography of Stalin, adding that the Soviet leader bore “the enormous workload”; that during the years of the war, he worked 14 or 15 hours a day; and that in the autumn of 1946 (after the end of the war), he went to the south of the country for a holiday for the first time since 1937 (nearly a decade).

Continuing, Losurdo remarks that a “similar assessment can be made of one of Stalin’s close collaborators, Lazar Kaganovich, who displays ‘frenzied commitment’ in overseeing the construction of the Moscow subway”, going down into the tunnels, including at night, to observe the condition of the workers. “To conclude, before us is a leadership group which demonstrates practically superhuman dedication, especially during the war years.” (pp156-7)

This real portrait of Comrade Stalin and his comrades gives the lie to the slanders hurled at him by Khrushchev and by the imperialist bourgeoisie; it is a far cry from Leon Trotsky’s snivelling about the ‘hated bureaucracy’.

What is more, “the ‘zealous faith’ that drives them isn’t limited to that inner circle, nor is it limited to members of the Communist party. ‘Average men and women’ also demonstrated their ‘missionary zeal’; as a whole, ‘it was a period of genuine enthusiasm, of feverish effort and voluntary sacrifice’.” (p157)

One can easily understand this spiritual climate if one realises that the country was experiencing surging stages of industrial development with giant strides, which furnished great possibilities for upward mobility to the masses of people – precisely when the capitalist world was in the middle of a devastating crisis of overproduction.

It was the dedication of the leadership that inspired the Stakhanovite movement and socialist emulation, which played a significant role in the accelerated industrialisation of the country.

George Kennan, the future architect of the USA’s ‘containment’ policy, who was a young American diplomat in 1932 in the Latvian capital Riga, described the Soviet Union as “the most morally united country in the world”. (p159)

It was not just rising living standards that triggered and motivated such enthusiasm. There was more: the genuine flourishing of nations that until then had been marginalised; the legal equality and an improvement in the status of women; the provision of a solid social welfare system that covered pensions, medical care and the protection of pregnant women; the phenomenal development of education and spread of intellectual activity, with the emergence of a network of libraries and reading rooms and an increasing passion amongst the masses for the arts and poetry.

It had all to do with “processes that characterise the entire history of Soviet Russia, but that take off precisely during the Stalin years”. (p160)

Masses of people hitherto condemned to a life of illiteracy made a tumultuous entrance into schools, universities and vocational colleges, giving rise to a generation of skilled workers, technicians and expert administrators, who went on to assume leadership roles.

New cities were founded and old cities were rebuilt; new and gigantic industrial enterprises in tandem with the upward mobility of skilled and enthusiastic workers of working-class and peasant origin – all gave rise to a period of remarkable heroism and spectacular achievement.

Even a cynical counter-revolutionary like Trotsky, became, against his will, infected, albeit momentarily, by the spirit of exhilaration and exaltation felt by the working masses, who could clearly see that the Soviet Union was shedding its medieval integument and catching up with the advanced developed countries.

“Gigantic achievements in industry, enormously promising beginnings in agriculture”, wrote Trotsky, “an extraordinary growth of old industrial cities and the building of new ones, a period of increase in the numbers of workers, rise in cultural levels and cultural demands – such are the indubitable results of the October Revolution, in which the prophets of the old world tried to see the grave of human civilisation.

“With the bourgeois economists we have no longer anything to quarrel over. Socialism has demonstrated its right to victory, not in the pages of Capital, but in the industrial arena comprising a sixth of the earth’s surface … Thanks solely to a proletarian revolution, a backward country has achieved in less than 20 years successes unexampled in history.”

Trotsky attributed these spectacular achievements to the October Revolution as if the leadership that planned and oversaw these achievements were irrelevant, although they could hardly have been achieved under someone like Trotsky, who had denied the very possibility of building socialism in the USSR.

Having cited the above paragraph from Trotsky, Losurdo correctly observes: “It is interesting to re-read the principal accusation made against the Soviet bureaucracy’s leadership formulated by Trotsky … It’s as if suddenly the indictment gives way to acknowledgements that are so important that they turn the indictment on its head.”

Trotsky continued: “In the schools of the Union, lessons are taught at present in no less than 80 languages. For a majority of them, it was necessary to compose new alphabets … Newspapers are published in the same number of languages – papers which for the first time acquaint the peasants and nomadic shepherds with the elementary ideas of human culture.

“Within the far-flung boundaries of the tsar’s empire, a native industry is arising. The old clan culture is being destroyed by the tractor. Together with literacy, scientific agriculture and medicine are coming into existence. It would be difficult to overestimate the significance of this work of raising up new human strata.”

One could not ask for a better refutation of Trotskyism – an admirable demolition of Trotskyism by Trotsky himself!

“Based on his image,” writes Losurdo, “it remains a mystery how Trotsky could have thought the anti-bureaucratic revolution was just round the corner. The acknowledgements, let slip by [Trotsky], are an indication of the prestige and consensus which the Soviet leadership enjoyed. The spread of a ‘new Soviet patriotism’ can’t be explained in any other way. It’s a sentiment that’s ‘certainly very deep, sincere and dynamic’.” (p161, our emphasis)

Stalin’s prestige and popularity reached its apex following the Soviet victory in the Great Patriotic War; and it remained intact until his death in March 1953, felt beyond the Soviet Union – even outside of the international communist movement.

Attack is the best form of defence runs the age-old adage. Imperialist ideologues, guided by this saying, have been busy for several decades bombarding the public with baseless slanders against the Soviet Union, and particularly against Josef Stalin. The real purpose of these attacks is to hide their own genocidal conduct, their own murderous activity and their racist affiliations.

Winston Churchill’s murky pro-fascist stance has been hidden from public gaze and he has been rebranded as a fearless fighter against fascism – not only by the bourgeois organs of propaganda but even by some who profess to be socialists. For instance, in speaking of Il Ducce (Mussolini) in 1933, Churchill declared: “The brilliant Roman personified by Mussolini, the greatest living legislator, showed many nations how to resist the pressures of socialism and showed the path that a nation can follow when it is courageously led.”

Four years later, when Italy had accomplished its brutal subjugation of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) and was busy overthrowing the Spanish republic, Churchill stated: “It would be an act of dangerous madness for the British people to underestimate the long-lasting position Mussolini would occupy in world history and the admirable qualities of courage, intelligence, self-control and perseverance that he personifies.” (p348)

Not only Mussolini, but also Churchill, being the arch-reactionary that he was, was favourably inclined towards all fascists and spoke of them in the most warm, affectionate and flattering terms. In 1937, he described Adfolf Hitler as an “extremely competent” politician with a “gallant manner” and a “disarming smile”, possessed of “subtle personal magnetism” that was difficult to escape.

Even more vociferous in Hitler’s praise was former British prime minister David Lloyd George, who spoke of the führer as a “great man” just before the start of the second world war. Hitler’s plans as announced in his Mein Kampf (the subjugation and enslavement of the Slavs) Lloyd George told the British ambassador in Berlin he considered acceptable, as long as the British empire were spared a similar fate.

As for the USA, in 1938 the American ambassador in Paris said that everything must be done to build a common front against “Asiatic despotism”, with the aim of preserving “European civilisation”. (p349)

These two countries were the darlings of the mercenary Robert Conquest, who portrayed them as the upholders of all that was good and virtuous.

As recently as 24 September 2023, a 98-year-old Ukrainian fascist Yareslav Hunka was hailed as a hero for fighting against the Russians during the second world war and given two standing ovations in the Canadian parliament. He had fought for the 14th division of the Waffen SS.

Following the embarrassment caused by this incident, the Canadians attempted to say they had not realised Hunka’s credentials. But anyone with a bare knowledge of the facts would know that those who fought against the USSR during that war could only have been Hitlerite fascists; it is beyond belief that several hundred Canadian parliamentarians giving a standing ovation to this fascist did not know who he was.

Of course they did. But so consumed were they by their hatred of Russia that they went ahead with honouring a fascist whose sentiments they presumably share. Volodymyr Zelensky, the head of the fascist Kiev junta, was standing next to Hunka, which says a lot about him. One of the participants in neo-nazi Nato’s proxy war against Russia, the Canadian imperialist government is siding with the Nazis in Ukraine; in view of this, the warm welcome to a Ukrainian fascist can come as no surprise.

There are many other examples of this imperialist hypocrisy and double standards, but the matters already dealt with above will suffice.

Critical observations

There are just a few critical observations about Losurdo’s book that are in order.

First, without the smallest shred of evidence, Losurdo claims that “the massacre of Polish officers, ordered by the Soviet leadership and carried out in March and April 1940 is a crime in itself”. (p306)

The truth is that the Nazis were responsible for that carnage. Anyone interested in this episode ought to look at Ella Rule’s excellent pamphlet on the Katyn massacre. It is worth pointing out that in the postwar Nuremberg trial of top Nazi criminals, the Nazi murder of Polish officers was one of the charges against the defendants.

Second, Losurdo says that at the start of the 1930s Stalin was not yet an autocrat. He adds: “It seems evident that, at least starting from 1937, and starting with the outbreak of the Great Terror, the dictatorship of the party gives way to autocracy.” (pp1412)

There are several things wrong with these assertions. There never was the dictatorship of the party; Losurdo appears to conflate the dictatorship of the proletariat with the dictatorship of the party. Doubtless the CPSU(B) was the guiding force of the dictatorship of the proletariat; however, he is entirely wrong to confuse the two.

By the ‘outbreak of the Great Terror’, he can only be alluding to the trial of traitors and criminals engaged in the undermining and overthrow of the Soviet regime. In that case, he ought not to have used this expression, which was coined by western intelligence agents turned ‘historians’, à la Robert Conquest, the incurable anticommunist propagandist in the service of imperialism, especially US imperialism.

During the collectivisation drive which, among other things, was aimed at liquidating the kulaks as a class (ie, removing their ability to carry on exploiting), the rich peasantry resorted to sabotage, murder and terror to frustrate this process. The Soviet authorities answered this counter-revolutionary terror with revolutionary terror. Would we not have the right to reproach them if they had failed to use this weapon and allowed the kulaks to emerge victorious from this period of intense class struggle?

In fact, when dealing with the period immediately following the October Revolution, Losurdo, saying that it would be “ideologically superficial to focus on the recourse to terrorist violence by only one of the actors”, quoted Orlando Figes’s description of the methods employed by anticommunist opponents of the Bolshevik regime:

“We’re dealing with a terrible, vengeful war against the communist regime. Thousands of Bolsheviks were brutally killed … Ears, tongues and eyes ripped out; limbs, heads and genitals cut off; stomachs emptied and filled with sand; foreheads and chests branded with crosses; people crucified upon trees, burnt alive, drowned in freezing water, buried up to their necks and fed upon by dogs and rats as a spectacle … Police stations and courthouses were destroyed. Schools and propaganda centres trashed.” (A People’s Tragedy, the Russian Revolution 1891-1924, cited on p111)

Kulak violence during collectivisation was equally ghastly and gruesome. This was a period of intensified class struggle during which the Bolshevik government and the popular masses of the peasantry employed revolutionary violence to stamp out the kulak counter-revolutionaries’ opposition. It is wrong to have expected the Bolsheviks to turn the other cheek.

It is also wrong to employ the term ‘terror’ as a neutral expression without designating the class nature of episodes or periods in which this terror was used. A revolution is not a leisurely stroll in a park; it involves a deadly struggle between hostile classes who fight with arms, bullets and bayonets. Losurdo is occasionally guilty of saying: terror is terror.

Following the successes of the collectivisation and industrialisation of the country, and the fulfilment of the two five-year plans, with their extraordinary results, under his leadership, Stalin came to acquire unprecedented prestige – a prestige that would reach its peak following the Soviet victory in the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet people.

He had undoubtedly become the most representative spokesman of the Soviet working class and masses, but to characterise his position as autocratic is to extend the meaning of the term autocracy beyond endurance. Autocracy is a system of government by one person with absolute power; in no way could the system of government in the USSR be described as an autocracy. Stalin was the first among equals – no more; and Losurdo’s own book is littered with examples to refute his unsubstantiated assertion.

Third, Losurdo more than once refers to collectivisation in the USSR as “forced” or “coerced” collectivisation that resulted in widespread violence. On p303 of his book he says: “forced collectivisation of agriculture had provoked, according to the far-sighted warning of Bukharin, ‘a Saint Bartholomew night’ for the rich peasantry and, more generally, for an enormous number of peasants’ belonging to national minorities.” (p150)

If collectivisation could be accomplished through force and coercion, the question arises: why wasn’t it attempted several years earlier, as Trotsky had demanded it should be? The answer of course is that the economic conditions for such a gigantic enterprise did not exist.

For a start, alternative sources for the supply of grain (to take the place of grain supplied by the kulaks) to the army and the urban population did not exist and had to be created. As Stalin never tired of emphasising, an offensive against the class of kulaks was a serious matter which could not be accomplished by mere declarations and the issue of government decrees. By 1929, the necessary conditions had been created. In addition, while the kulaks had begun withholding grain from the market, the danger of war was looming larger than ever.

The “thesis formulated by Toynbee, according to which [victory at] Stalingrad was made possible by the journey taken by Stalin’s USSR ‘from 1928 to 1941’ (The world at war) is today confirmed by no small number of historians and experts on military strategy. It is quite possible that, without abandonment of the NEP [New Economic Policy], without the collectivisation of agriculture (with the steady flow of food products from the countryside to the city and the front) and the rushed industrialisation (with the development of the arms industry and with the rise of new industrial centres in the eastern regions, at a safe distance from the invading army), it would have been impossible to successfully oppose Hitler’s aggression.”

Losurdo cites Arno Mayer’s Why Did the Heavens Not Darken?: “The unequalled and incontestable contribution by Soviet Russia to the defeat of Nazi Germany is closely linked to the stubborn Second Revolution [collectivisation and industrialisation] by Stalin.” Losurdo adds that: “in Churchill’s judgment, even the trial against Tukhachevsky and the Great Terror as a whole played a positive and even an important role in the defeat of Operation Barbarossa” [the Nazi invasion of the USSR on 22 June 1941]. (p303-4)

Elsewhere Losurdo writes: “At the end of 1920s, collectivisation of agriculture seemed to be the mandatory route to significantly accelerate the country’s industrialisation and to secure the stable supply of provisions needed by the cities and the army, all in preparation for war.” (p149)

And the economic results of the first five-year plan were simply stunning, with industrial production increasing by 250 percent, as a result of which the USSR took giant steps in transforming itself into a major industrial power and her arms industry took a great leap forward.

Apart from the urgency of collectivisation and industrialisation, the economic conditions for this unprecedented enterprise had been methodically and meticulously prepared and, notwithstanding contrary assertions from a host of sources, it had been a voluntary affair on the part of the masses, with the exception of the kulaks. Losurdo himself admits that the process had been “in part driven by the peasantry from below”. (p103) [Anyone interested in the subject is referred to the chapter on collectivisation in Trotskyism or Leninism? by Harpal Brar].

Again: “One can’t underestimate the pressure from below; in not unimportant sectors of the society.” (p146)

Elsewhere in his book, Losurdo says that Stalin emphasised the need to convince peasants about the need for collectivisation (ie, not to force them into it against their will!) “sparing neither time nor effort”.

Fourth, Losurdo gives a most pathetic explanation for the downfall of the Soviet Union: “Like the Jacobins,” he writes, “the Bolsheviks are unable to adjust to the disappearance or attenuation of the state of emergency, and they therefore end [up] seeming obsolete and superficial to the majority of the population. After having managed to overcome the ‘crisis of the entire Russian nation’, the Bolsheviks in the end were defeated by the arrival of that relative state of normality, that was itself the outcome of their efforts.”

In other words, to prolong socialism, the Bolsheviks should have worked for the exacerbation of international tensions as well as internal contradictions. This is not an explanation but a mockery of an an explanation as to the cause of the disappearance of the USSR. For a meaningful explanation of the Soviet Union’s collapse, we invite the reader to have a look at Harpal Brar’s book Perestroika – the Complete Collapse of Revisionism.

Notwithstanding these weaknesses, Losurdo’s book has done a wonderful service in demolishing the attempts by Trotsky, Khrushchev and the various imperialist commentators to demonise Stalin and, by extension, the cause of communism. For decades, imperialism’s anticommunist campaign had centred on the demonisation of Stalin.

Attacking revolutions by attacking their leaders

Up until the disappearance of the USSR, Hitler was held to have had only one ‘monstrous twin’, and he had been at the helm in Moscow for three decades and continued to loom over the country that had defeated Nazi Germany and had dared to challenge US hegemony.

There weren’t such hyperbolic polemics against Chairman Mao Zedong until, with the prodigious rise of China, attempts were afoot to denude the People’s Republic of its identity and self-esteem. From then on, the ideologues of imperialism were “determined to identify Hitler’s other monstrous twin”. Enter the anti-Mao campaign and the maliciously slanderous book by Chang Yung and Jon Halliday: Mao – the Unknown Story, a work of fiction and fabrication that characterised Mao as the greatest criminal of the 20th century, or maybe of all time.

This disgraceful duo started their assault by examining the so-called Monster’s childhood instead of by looking at China’s history. It is therefore necessary to make a reference to China’s history. For centuries, China had occupied a leading position in the development of human civilisation. As late as the 1820s it accounted for 32.4 percent of global GDP. However, in 1949, at the time of New China’s foundation, it was one of the poorest countries in the world – such was the result of a century of humiliation at the hands of colonialist and imperialist powers.

This century of humiliation, beginning with the Opium wars, characterised by the ubiquitous prevalence of British narco-traffickers, recurrent famines, warlordism, banditry (an estimated 20 million bandits by around 1930, accounting for 20 percent of the Chinese population), widespread prostitution and the poverty-driven sale of wives and children by peasants – all with the support and complicity of western concessions, who found in the misery of the Chinese people a source of fabulous profits.

And, after liberation, China was subjected by imperialism to a draconian economic blockade designed to starve the Chinese people and cause the maximum number of deaths.

All this history disappears from imperialist historiography and propaganda, among which must be counted Jang and Halliday’s disgraceful book. Precisely for this reason, their book, lacking entirely in scholarship or serious research, has had great success. The truth, as Losurdo points out, is that “just as in Russia, in China it’s ultimately the revolution led by the Communist party that saved the nation and even the state”. (p338)

Thankfully, the Chinese revolution saved the Chinese people literally from annihilation and enabled them to avoid being afflicted by the fate suffered by the American natives – a fate of which modern China’s founder, Dr Sun Yat-sen, was rightly fearful.

“In reality,” writes Losurdo, “the social conquests of the Mao era are extraordinary, conquests that achieved a clear improvement in economic, social and cultural conditions, and a big increase in the Chinese people’s life expectancy; without that basis, one can’t understand prodigious economic development later that freed hundreds of millions of people from hunger and even starvation.

“But in the ruling [imperialist] ideology, one witnesses a true inversion of responsibilities: the political leadership that put an end to the century of humiliation become a gang of criminals, while those responsible for the immense century-long tragedy, and those who with their embargo did everything to prolong it, become the champions of freedom and civilisation.” (pp341-2)

This falsification of the history of revolutionary countries and the demonisation of their top leaders – Mao Zedong and Josef Stalin – is accompanied by a glaring omission of the crimes of imperialism. While communist and anti-imperialist leaders are transformed into Hitler’s ‘twin monsters’, the real criminal monsters – from Harry Truman, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Bill Clinton, George W Bush, Barack Obama and Joe Biden to Tony Blair and Boris Johnson are portrayed as peace-loving leaders of the free world!

The genocides committed under the watch of these criminals, with the slaughter of millions of people in imperialism’s predatory wars against the people of Korea, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Indonesia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Syria, Ukraine and more, are simply ignored.

Losurdo exposes this hypocrisy admirably. Precisely because of this, various publishers refused to publish his book in English.

Left-leaning publishers of Losurdo’s other books including Verso refused to touch it. When approached for publication, Verso senior editor Sebastian Budgen called it “one of Losurdo’s worst books”, adding: “We shall continue to publish the books by him that have intellectual merit and are based on real and serious research, but not these kinds of texts.”

Yet the book’s translator, Henry Hamasäki, has noted that the book has at least “346 works cited in it, and well over 1,000 points of citation within the text”. What is clear is that Verso refused publication because the book challenges the agreed anti-Stalin narrative of bourgeois historiography, no matter how well researched. The very title of the book is a reference to the idea that a “black legend” has been fabricated around Stalin so as to discredit him and portray him as a monstrous figure without redeeming qualities.

Losurdo’s book is a “history and critique” of the demonisation of Stalin. Based on rigorous and well-documented scholarship, it shatters this “black legend” systematically and methodically, pointing out how the history of Stalin and his three-decade long stewardship of the Soviet Union and the international communist movement has been decontextualised, distorted, fabricated, calumnised and exaggerated, with the sole purpose of creating a political mythology about Stalin as a congenital villain.

In truth, Stalin stands out as a giant in the history of the international communist movement – an outstanding Marxist-Leninist theoretician, under whose leadership the Soviet Union accomplished almost miraculous achievements in the field of industrialisation, the collectivisation of agriculture; advances in the fields of science, technology, the arts; progress in the sphere of healthcare, housing and social provision, and the emancipation of women; and the crowning victory in the Great Patriotic War – a victory that saved not only the Soviet people but humanity at large from slavery under the jackboot of Hitlerite fascism.

Those who are in the business of fighting for the victory of socialism are duty-bound to make a study of the real Stalin – a giant revolutionary, a great Marxist theoretician, a builder of socialism, and the undisputed leader of the communist movement – and not to be fooled by the black legend sought to be built around his name by the paid mercenaries of the imperialist bourgeoisie.

Demonisation of Stalin has always been aimed at the demonisation of communism and the dictatorship of the proletariat. From bourgeois academics to renegades from communism such as Khrushchev and Trotsky, the anti-Stalin narrative has been the stock-in-trade of those who do not have the courage to launch a direct assault on Marxism-Leninism.

Masses of people in the vast continents of Africa, Asia and Latin America, have almost instinctively grasped this truth. They understand that under Stalin’s leadership the Soviet Union abolished illiteracy, put an end to unemployment, the scourge of the working class, did away with the recurrent periodic cycles of overproduction, provided universal healthcare and decent housing, brought to an end the famines that had plagued pre-Bolshevik Russia and, having smashed fascism, brought socialism to eastern and central European countries, all while giving tremendous assistance to the national-liberation movements of the oppressed countries. Precisely for these reasons Stalin has always been held in high regard in these vast continents.

Losurdo quite correctly points out that, while the Trotskyites have long condemned ‘Stalinism’ with impotent rage, the real origin of Stalin’s demonisation in the centres of imperialism dates from Khrushchev’s so-called ‘secret speech’ to the 20th congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956 “on the cult of the personality and its consequences”.

Losurdo demolishes Khrushchev’s claims by reference to solid historical facts. Following that, he deals, one by one, with many charges against Stalin from then on, looking at the historical, political and social context in its entirety, thus helping the reader come to an understanding of what really took place under Stalin’s leadership. At the end of the book, we are left with a picture of Stalin that is dramatically different from the one which we usually get from what passes for historiography in bourgeois circles.

Losurdo observes that with progress of scholarship, “on the whole, the caricatured portrait of Stalin drawn first by Trotsky and then by Khrushchev no longer enjoys much credit”, adding: “It now becomes clear that the secret speech is entirely unreliable. There is no detail in it that is not contested today.”

From the research by eminent scholars who cannot be suspected of having indulged in the ‘cult of the personality’, the portrait that emerges is of a proletarian revolutionary and devout Marxist-Leninist “who rises and secures the positions of power in the USSR primarily for the fact that he widely” surpasses his opponents when it comes to “understanding how the Soviet Union operated, a leader of ‘exceptional political talent’ and ‘enormously gifted’; a statesman who saved the Russian nation from annihilation and enslavement thanks not only to his astute military strategy but also his ‘masterful’ wartime speeches, speeches that are at times authentically ‘brilliant’ that in tragic or decisive moments manage to encourage national resistance; a figure who does not lack qualities when it comes to theory as demonstrated by the insight with which he dealt with the national question in his writing from 1913, his ‘contribution’ to the linguistic question among others.” (pp324-5)

And yet the black legend constructed around Stalin by imperialist historiography still remains a cornerstone of the anti-Stalin, anticommunist campaigns in the bourgeois world. Losurdo’s book is a very important contribution to understanding the real Stalin and his gigantic contribution to the struggle for the overthrow of capitalism and the construction of socialism; it is destined to discredit the predominant, anticommunist history that is inculcated at every layer of society in the imperialist countries.

At a time when increasing numbers of people in what is described as the west are being attracted to the ideology of revolutionary Marxism-Leninism, when imperialism’s utter decadence is being revealed by life, everyone interested in socialism should read this book.