Jacques Baud is a former colonel of the Swiss general staff, ex-member of strategic intelligence and a specialist on eastern countries who has trained with British and American intelligence and worked at both Nato and the United Nations in various capacities. He is the author of several books on intelligence, war and terrorism, including ‘Le Détournement’, ‘Gouverner par les Fake News, L’affaire Navalny’ and ‘Poutine, Maître du Jeu?’.

We reproduce this article from the Postil Magazine with thanks. It was originally published by the Centre Français de Recherche sur le Renseignement in Paris and translated from the French by N Dass.

*****

Part one: The road to war

For years, from Mali to Afghanistan, I have worked for peace and risked my life for it. It is therefore not a question of justifying war, but of understanding what led us to it. I notice that the ‘experts’ who take turns on television analyse the situation on the basis of dubious information, most often hypotheses erected as facts — and then we can no longer understand what is happening. This is how panics are created.

The problem is not so much to know who is right in this conflict, but to question the way our leaders make their decisions.

Let’s try to examine the roots of the conflict. It starts with those who for the last eight years have been talking about ‘separatists’ or ‘independentists’ from Donbass. This is not true. The referendums conducted by the two self-proclaimed republics of Donetsk and Lugansk in May 2014 were not referendums of ‘independence’ (независимость), as some unscrupulous journalists have claimed, but referendums of ‘self-determination’ or ‘autonomy’ (самостоятельность). The qualifier ‘pro-Russian’ suggests that Russia was a party to the conflict, which was not the case, and the term ‘Russian speakers’ would have been more honest. Moreover, these referendums were conducted against the advice of Vladimir Putin.

In fact, these republics were not seeking to separate from Ukraine, but to have a status of autonomy, guaranteeing them the use of the Russian language as an official language. For the first legislative act of the new government resulting from the overthrow of President Yanukovych, was the abolition, on 23 February 2014, of the Kivalov-Kolesnichenko law of 2012 that made Russian an official language. It was as if putschists had decided that French and Italian would no longer be official languages in Switzerland.

This decision caused a storm among the Russian-speaking population. The result was a fierce repression against the Russian-speaking regions (Odessa, Dnepropetrovsk, Kharkov, Lugansk and Donetsk), which began in February 2014 and led to a militarisation of the situation and some massacres (in Odessa and Marioupol being the most notable). At the end of summer 2014, only the self-proclaimed republics of Donetsk and Lugansk remained.

At this stage, too rigid and engrossed in a doctrinaire approach to the art of operations, the Ukrainian general staff subdued the enemy without managing to prevail. The examination of the course of the fighting in 2014-16 in the Donbass shows that the Ukrainian general staff systematically and mechanically applied the same operative schemes. However, the war waged by the autonomists was very similar to what we observed in the Sahel: highly mobile operations conducted with light means. With a more flexible and less doctrinaire approach, the rebels were able to exploit the inertia of Ukrainian forces to repeatedly ‘trap’ them.

In 2014, when I was at Nato, I was responsible for the fight against the proliferation of small arms, and we were trying to detect Russian arms deliveries to the rebels, to see if Moscow was involved. The information we received then came almost entirely from Polish intelligence services and did not ‘fit’ with the information coming from the OSCE — despite rather crude allegations, there were no deliveries of weapons and military equipment from Russia.

The rebels were armed thanks to the defection of Russian-speaking Ukrainian units that went over to the rebel side. As Ukrainian failures continued, tank, artillery and anti-aircraft battalions swelled the ranks of the autonomists. This is what pushed the Ukrainians to commit to the Minsk agreements.

But just after signing the Minsk 1 agreements, the Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko launched a massive anti-terrorist operation (ATO/Антитерористична операція) against the Donbass. Bis repetita placent: poorly advised by Nato officers, the Ukrainians suffered a crushing defeat in Debaltsevo, which forced them to engage in the Minsk 2 agreements.

It is essential to recall here that Minsk 1 (September 2014) and Minsk 2 (February 2015) agreements did not provide for the separation or independence of the republics, but their autonomy within the framework of Ukraine. Those who have read the agreements (and there are very, very, very few who actually have) will note that it is written in all letters that the status of the republics was to be negotiated between Kiev and the representatives of the republics, for an internal solution to Ukraine’s problems.

That is why, since 2014, Russia has systematically demanded their implementation while refusing to be a party to the negotiations, because it was an internal matter for Ukraine. On the other side, the west – led by France – systematically tried to replace the Minsk agreements with the ‘Normandy format’, which put Russians and Ukrainians face-to-face.

However, let us remember that there were never any Russian troops in the Donbass before 23-24 February 2022. Moreover, OSCE observers have never observed the slightest trace of Russian units operating in the Donbass. For example, the US intelligence map published by the Washington Post on 3 December 2021 does not show Russian troops in the Donbass.

In October 2015, Vasyl Hrytsak, director of the Ukrainian security service (SBU), confessed that only 56 Russian fighters had been seen in the Donbass. This was exactly comparable to the Swiss who went to fight in Bosnia on weekends in the 1990s, or the French who go to fight in Ukraine today.

The Ukrainian army was then in a deplorable state. In October 2018, after four years of war, chief Ukrainian military prosecutor Anatoly Matios stated that Ukraine had lost 2,700 men in the Donbass: 891 from illnesses, 318 from road accidents, 177 from other accidents, 175 from poisonings (alcohol, drugs), 172 from careless handling of weapons, 101 from breaches of security regulations, 228 from murders and 615 from suicides.

In fact, the army was undermined by the corruption of its cadres and no longer enjoyed the support of the population. According to a British Home Office report, in the March/April 2014 recall of reservists, 70 percent did not show up for the first session, 80 percent for the second, 90 percent for the third, and 95 percent for the fourth. In October/November 2017, 70 percent of conscripts did not show up for the Fall 2017 recall campaign. This is not counting suicides and desertions (often over to the autonomists), which reached up to 30 percent of the workforce in the ATO area.

Young Ukrainians refused to go and fight in the Donbass and preferred emigration, which also explains, at least partially, the demographic deficit of the country.

The Ukrainian ministry of defence then turned to Nato to help make its armed forces more ‘attractive’. Having already worked on similar projects within the framework of the United Nations, I was asked by Nato to participate in a programme to restore the image of the Ukrainian armed forces. But this is a long-term process and the Ukrainians wanted to move quickly.

So, to compensate for the lack of soldiers, the Ukrainian government resorted to paramilitary militias. They are essentially composed of foreign mercenaries, often extreme right-wing militants. In 2020, they constituted about 40 percent of the Ukrainian forces and numbered about 102,000 men, according to Reuters. They were armed, financed and trained by the United States, Great Britain, Canada and France. There were more than 19 nationalities – including Swiss.

Western countries have thus clearly created and supported Ukrainian far-right militias. In October 2021, the Jerusalem Post sounded the alarm by denouncing the Centuria project. These militias had been operating in the Donbass since 2014, with western support …

These militias, originating from the far-right groups that animated the Euromaidan revolution [coup] in 2014, are composed of fanatical and brutal individuals. The best known of these is the Azov regiment, whose emblem is reminiscent of the second SS Das Reich Panzer division, which is revered [amongst some] in Ukraine for liberating Kharkov from the Soviets in 1943, before carrying out the 1944 Oradour-sur-Glane massacre in France.

Among the famous figures of the Azov regiment was the opponent Roman Protasevich, arrested in 2021 by the Belarusian authorities following the case of RyanAir flight FR4978. On 23 May 2021, the deliberate hijacking of an airliner by a MiG-29 – supposedly with Putin’s approval – was mentioned as a reason for arresting Protasevich, although the information available at the time did not confirm this scenario at all.

But then it was necessary to show that President Lukashenko was a thug and Protasevich a ‘journalist’ who loved democracy. However, a rather revealing investigation produced by an American NGO in 2020 highlighted Protasevich’s far-right militant activities. The western conspiracy movement then started, and unscrupulous media ‘air-brushed’ his biography.

Finally, in January 2022, the ICAO report was published and showed that despite some procedural errors, Belarus acted in accordance with the rules in force and that the MiG-29 took off 15 minutes after the RyanAir pilot decided to land in Minsk. So no Belarusian plot and even less Putin. Ah! … another detail: Protasevich, cruelly tortured by the Belarusian police, was now free. Those who would like to correspond with him can go on his Twitter account.

The characterisation of the Ukrainian paramilitaries as Nazis or neo-Nazis is considered Russian propaganda. Perhaps. But that’s not the view of the Times of Israel, the Simon Wiesenthal Centre or the West Point academy’s Centre for Counterterrorism. But that’s still debatable, because in 2014, Newsweek magazine seemed to associate them more with … the Islamic State. Take your pick!

So, the west supported and continued to arm militias that have been guilty of numerous crimes against civilian populations since 2014: rape, torture and massacres. But while the Swiss government has been very quick to take sanctions against Russia, it has not adopted any against Ukraine, which has been massacring its own population since 2014.

In fact, those who defend human rights in Ukraine have long condemned the actions of these groups, but have not been supported by our governments. Because, in reality, we are not trying to help Ukraine, but to fight Russia.

The integration of these paramilitary forces into the national guard was not at all accompanied by a ‘denazification’, as some claim. Among the many examples, that of the Azov regiment’s insignia is instructive:

In 2022, very schematically, the Ukrainian armed forces fighting the Russian offensive were organised as:

• The army, subordinated to the ministry of defence. This is organised into three army corps and composed of manoeuvre formations (tanks, heavy artillery, missiles, etc).

• The national guard, which answers to the ministry of the interior and is organised into five territorial commands.

The national guard is therefore a territorial defence force that is not part of the Ukrainian army. It includes paramilitary militias, called ‘volunteer battalions’ (добровольчі батальйоні), also known by the evocative name of ‘reprisal battalions’, and composed of infantry. Primarily trained for urban combat, it now defends cities such as Kharkov, Mariupol, Odessa, Kiev, etc.

Part two: The war

As a former head of the Warsaw Pact forces in the Swiss strategic intelligence service, I observe with sadness – but not astonishment – that our services are no longer able to understand the military situation in Ukraine. The self-proclaimed ‘experts’ who parade on our screens tirelessly relay the same information modulated by the claim that Russia – and Vladimir Putin – is irrational. Let’s take a step back.

1. The outbreak of war

Since November 2021, the Americans have been constantly threatening a Russian invasion of the Ukraine. However, the Ukrainians did not seem to agree. Why not?

We have to go back to 24 March 2021. On that day, Volodymyr Zelensky issued a decree for the recapture of the Crimea, and began to deploy his forces to the south of the country. At the same time, several Nato exercises were conducted between the Black Sea and the Baltic Sea, accompanied by a significant increase in reconnaissance flights along the Russian border. Russia then conducted several exercises to test the operational readiness of its troops and to show that it was following the evolution of the situation.

Things calmed down until October/November with the end of the ZAPAD 21 exercises, whose troop movements were interpreted as a reinforcement for an offensive against Ukraine. However, even the Ukrainian authorities refuted the idea of Russian preparations for a war, and Ukrainian defence minister Oleksiy Reznikov stated that there had been no change in its border since the spring.

In violation of the Minsk agreements, Ukraine was conducting air operations in the Donbass using drones, including at least one strike against a fuel depot in Donetsk in October 2021. The American press noted this, but not the Europeans; and no one condemned these violations.

In February 2022, events were precipitated. On 7 February, during his visit to Moscow, Emmanuel Macron reaffirmed to Vladimir Putin his commitment to the Minsk agreements, a commitment he would repeat after his meeting with Volodymyr Zelensky the next day. But on 11 February, in Berlin, after nine hours of work, the meeting of political advisors of the leaders of the ‘Normandy format’ ended without any concrete result: the Ukrainians still refused to apply the Minsk agreements, apparently under pressure from the United States.

Vladimir Putin noted that Macron had made empty promises and that the west was not ready to enforce the agreements, and that it had been refusing to do so for eight years.

Ukrainian preparations in the contact zone continued. The Russian parliament became alarmed, and on 15 February asked Vladimir Putin to recognise the independence of the Donbass republics, which he refused to do.

On 17 February, US president Joe Biden announced that Russia would attack Ukraine in the next few days. How did he know this? It is a mystery. But from the 16th onwards, artillery shelling of the population of Donbass increased dramatically, as the daily reports of the OSCE observers show.

Naturally, neither the media, nor the European Union, nor Nato, nor any western government reacted or intervened. It would be said later that this was Russian disinformation. In fact, it seems that the European Union and some other countries have deliberately kept silent about the massacre of the Donbass population, knowing that this would provoke a Russian intervention.

At the same time, there were reports of sabotage in the Donbass. On 18 January, Donbass fighters intercepted saboteurs who spoke Polish, carried western equipment and were seeking to create a chemical incident in Gorlivka. They could have been CIA mercenaries, led or ‘advised’ by Americans and composed of Ukrainian or European fighters to carry out sabotage actions in the Donbass republics.

In fact, as early as 16 February, Joe Biden knew that the Ukrainians had begun shelling the civilian population of Donbass, leaving Vladimir Putin with a difficult choice: to help the Donbass militarily and create an international problem, or to stand by and watch the Russian-speaking people there being crushed.

If he decided to intervene, Putin could invoke the international obligation of ‘Responsibility To Protect’ (R2P). But he knew that whatever its nature or scale, the intervention would trigger a storm of sanctions. Therefore, whether Russian intervention were limited to the Donbass or went further, to put pressure on the west regarding the status of Ukraine, the price to pay would be the same. This is what he explained in his speech on 21 February.

On that day, he agreed to the request of the Duma and recognised the independence of the two Donbass republics. At the same time, he signed friendship and assistance treaties with them.

The Ukrainian artillery bombardment of the Donbass population continued, and, on 23 February, the two republics asked for military assistance from Russia. On 24 February, Vladimir Putin invoked Article 51 of the United Nations charter, which provides for mutual military assistance within the framework of a defensive alliance.

In order to make the Russian intervention totally illegal in the eyes of the public, our media deliberately hid the fact that the war actually started on 16 February. The Ukrainian army was preparing to attack the Donbass as early as 2021, as some Russian and European intelligence services were well aware. Jurists will judge.

In his speech of 24 February, Vladimir Putin stated the two objectives of his operation: “demilitarise” and “denazify” Ukraine. So, it is not a question of taking over Ukraine, nor even, presumably, of occupying it; and certainly not of destroying it.

From then on, our visibility on the course of the operation is limited: the Russians have excellent security of operations (opsec) and the details of their planning are not known. But fairly quickly, the course of the operation allows us to understand how the strategic objectives are being translated on the operational level.

Demilitarisation:

• Ground destruction of Ukrainian aviation, air defense systems and reconnaissance assets.

• Neutralisation of command and intelligence structures (C3I), as well as the main logistical routes in the depth of the territory.

• Encirclement of the bulk of the Ukrainian army massed in the southeast of the country.

Denazification:

• Destruction or neutralisation of volunteer battalions operating in the cities of Odessa, Kharkov and Mariupol, as well as in various facilities in the territory.

2. Demilitarisation

The Russian offensive was carried out in a very ‘classic’ manner. Initially – as the Israelis had done in 1967 – with the destruction on the ground of the air force in the very first hours. Then we witnessed a simultaneous progression along several axes according to the principle of ‘flowing water’: advance everywhere where resistance was weak and leave the cities (very demanding in terms of troops) for later.

In the north, the Chernobyl power plant was occupied immediately to prevent acts of sabotage. The images of Ukrainian and Russian soldiers guarding the plant together are of course not shown in western media.

The idea that Russia was trying to take over Kiev, the capital, to eliminate Zelensky, comes typically from the west – that is what they did in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya, and what they wanted to do in Syria with the help of the Islamic State.

But Vladimir Putin never intended to shoot or topple Zelensky. Instead, Russia seeks to keep him in power by pushing him to negotiate, by surrounding Kiev. Up till now, he had refused to implement the Minsk agreements. But now the Russians want to obtain the neutrality of Ukraine.

Many western commentators were surprised that the Russians continued to seek a negotiated solution while conducting military operations. The explanation lies in the Russian strategic outlook since the Soviet era. For the west, war begins when politics ends. However, the Russian approach follows a Clausewitzian inspiration: war is the continuity of politics and one can move fluidly from one to the other, even during combat. This allows one to create pressure on the adversary and push him to negotiate.

From an operational point of view, the Russian offensive was an example of its kind: in six days, the Russians seized a territory as large as the United Kingdom, with a speed of advance greater than the Wehrmacht had achieved in 1940.

The bulk of the Ukrainian army was deployed in the south of the country in preparation for a major operation against the Donbass. This is why Russian forces were able to encircle it from the beginning of March in the ‘cauldron’ between Slavyansk, Kramatorsk and Severodonetsk, with a thrust from the east through Kharkov and another from the south from Crimea. Troops from the Donetsk (DPR) and Lugansk (LPR) republics are complementing the Russian forces with a push from the east.

At this stage, Russian forces are slowly tightening the noose, but are no longer under time pressure. Their demilitarisation goal is all but achieved and the remaining Ukrainian forces no longer have an operational and strategic command structure.

The ‘slowdown’ that our ‘experts’ attribute to poor logistics is only the consequence of having achieved their objectives. Russia does not seem to want to engage in an occupation of the entire Ukrainian territory. In fact, it seems that Russia is trying to limit its advance to the linguistic border of the country.

Our media speak of indiscriminate bombardments against the civilian population, especially in Kharkov, and Dantean images are broadcast in a loop. However, Gonzalo Lira, a Latin American who lives there, presents us with a calm city on 10 March and 11 March. It is true that it is a large city and we do not see everything – but this seems to indicate that we are not in the total war that we are served continuously on our screens.

As for the Donbass republics, they have ‘liberated’ their own territories and are fighting in the city of Mariupol.

3. Denazification

In cities like Kharkov, Mariupol and Odessa, the defence is provided by paramilitary militias. They know that the objective of ‘denazification’ is aimed primarily at them.

For an attacker in an urbanised area, civilians are a problem. This is why Russia is seeking to create humanitarian corridors to empty cities of civilians and leave only the militias, to fight them more easily.

Conversely, these militias seek to keep civilians in the cities in order to dissuade the Russian army from fighting there. This is why they are reluctant to implement these corridors and do everything to ensure that Russian efforts are unsuccessful – they can use the civilian population as ‘human shields’. Videos showing civilians trying to leave Mariupol and beaten up by fighters of the Azov regiment are of course carefully censored here.

On Facebook, the Azov group was considered in the same category as the Islamic State and subject to the platform’s “policy on dangerous individuals and organizations”. It was therefore forbidden to glorify it, and posts that were favourable to it were systematically banned. But on 24 February, Facebook changed its policy and allowed posts favourable to the militia.

In the same spirit, in March, the platform authorised, in the former eastern countries, calls for the murder of Russian soldiers and leaders. So much for the values that inspire our leaders, as we shall see.

Our media propagate a romantic image of ‘popular resistance’. It is this image that led the European Union to finance the distribution of arms to the civilian population.

This is a criminal act. In my capacity as head of peacekeeping doctrine at the UN, I worked on the issue of civilian protection. We found that violence against civilians occurred in very specific contexts. In particular, when weapons are abundant and there are no command structures.

These command structures are the essence of armies: their function is to channel the use of force towards an objective. By arming citizens in a haphazard manner, as is currently the case, the EU is turning them into combatants, with the consequential effect of making them potential targets. Moreover, without command, without operational goals, the distribution of arms leads inevitably to settling of scores, banditry and actions that are more deadly than effective. War becomes a matter of emotions. Force becomes violence.

This is what happened in Tawarga (Libya) from 11-13 August 2011, where 30,000 black Africans were massacred with weapons parachuted (illegally) by France. By the way, the British Royal Institute for Strategic Studies (RUSI) does not see any added value in these arms deliveries.

Moreover, by delivering arms to a country at war, one exposes oneself to being considered a belligerent. The Russian strikes of 13 March 2022, against the Mykolayev air base follow Russian warnings that arms shipments would be treated as hostile targets.

The EU is repeating the disastrous experience of the Third Reich in the final hours of the Battle of Berlin. War must be left to the military, and when one side has lost, it must be admitted. And if there is to be resistance, it must be led and structured. But we are doing exactly the opposite – we are pushing citizens to go and fight, and at the same time, Facebook authorises calls for the murder of Russian soldiers and leaders. So much for the values that inspire us.

Some intelligence services see this irresponsible decision as a way to use the Ukrainian population as cannon fodder to fight Vladimir Putin’s Russia. This kind of murderous decision should have been left to the colleagues of Ursula von der Leyen’s grandfather. It would have been better to engage in negotiations and thus obtain guarantees for the civilian population than to add fuel to the fire. It is easy to be combative with the blood of others.

4. The Maternity Hospital At Mariupol

It is important to understand beforehand that it is not the Ukrainian army that is defending Marioupol, but the Azov militia, composed of foreign mercenaries.

In its 7 March 2022 summary of the situation, the Russian UN mission in New York stated: “Residents report that Ukrainian armed forces expelled staff from the Mariupol city birth hospital No 1 and set up a firing post inside the facility.”

On 8 March, the independent Russian media Lenta.ru published the testimony of civilians from Marioupol. They reported that the maternity hospital had been taken over by the militia of the Azov regiment, who drove out the civilian occupants by threatening them with their weapons. They confirmed the statements of the Russian ambassador a few hours earlier.

The hospital in Mariupol occupies a dominant position, perfectly suited for the installation of anti-tank weapons and for observation. On 9 March, Russian forces struck the building. According to CNN, 17 people were wounded, but the images do not show any casualties in the building and there is no evidence that the victims mentioned are related to this strike.

There was talk of children, but in reality, there is nothing. This may be true, but it may not be true. This does not prevent the leaders of the EU from seeing this as a war crime. And this allows Zelensky to call for a ‘no-fly zone’ over Ukraine.

In reality, we do not know exactly what happened. But the sequence of events tends to confirm that Russian forces struck a position of the Azov regiment and that the maternity ward was at that time free of civilians.

The problem is that the paramilitary militias that defend the cities are encouraged by the international community not to respect the customs of war. It seems that the Ukrainians have replayed the scenario of the Kuwait City maternity hospital in 1990, which was totally staged by the firm Hill & Knowlton for $10.7m in order to convince the United Nations security council to intervene in Iraq for Operation Desert Shield/Storm.

Western politicians have accepted civilian strikes in the Donbass for eight years, without adopting any sanctions against the Ukrainian government. We have long since entered a dynamic where western politicians have agreed to sacrifice international law towards their goal of weakening Russia.

Part three: Conclusions

As an ex-intelligence professional, the first thing that strikes me is the total absence of western intelligence services in the representation of the situation over the past year. In Switzerland, the services have been criticised for not having provided a correct picture of the situation.

In fact, it seems that throughout the western world, intelligence services have been overwhelmed by the politicians. The problem is that it is the politicians who decide – the best intelligence service in the world is useless if the decision-maker does not listen. This is what happened during this crisis.

That said, while some intelligence services had a very accurate and rational picture of the situation, others clearly had the same picture as that propagated by our media. In this crisis, the services of the countries of the ‘new Europe’ played an important role.

The problem is that, from experience, I have found them to be extremely bad at the analytical level – doctrinaire, they lack the intellectual and political independence necessary to assess a situation with military ‘quality’. It is better to have them as enemies than as friends.

Second, it seems that in some European countries, politicians have deliberately ignored their services in order to respond ideologically to the situation. That is why this crisis has been irrational from the beginning. It should be noted that all the documents that were presented to the public during this crisis were presented by politicians based on commercial sources.

Some western politicians obviously wanted there to be a conflict. In the United States, the attack scenarios presented by Anthony Blinken to the security council were only the product of the imagination of a Tiger Team working for him – he did exactly as Donald Rumsfeld did in 2002, who had thus ‘bypassed’ the CIA and other intelligence services that were much less assertive about Iraqi chemical weapons.

The dramatic developments we are witnessing today have causes that we knew about but refused to see:

• On the strategic level, the expansion of Nato (which we have not dealt with here).

• On the political level, the western refusal to implement the Minsk agreements.

• Operationally, the continuous and repeated attacks on the civilian population of the Donbass over the past years and the dramatic increase in late February 2022.

In other words, we can naturally deplore and condemn the Russian attack. But we (that is: the United States, France and the European Union in the lead) have created the conditions for a conflict to break out.

We show compassion for the Ukrainian people and the two million refugees. That is fine. But if we had had a modicum of compassion for the same number of refugees from the Ukrainian populations of Donbass massacred by their own government and who sought refuge in Russia for eight years, none of this would probably have happened.

Whether the term ‘genocide’ applies to the abuses suffered by the people of Donbass is an open question. The term is generally reserved for cases of greater magnitude (Holocaust, etc). But the definition given by the Genocide convention is probably broad enough to apply to this case. Legal scholars will understand this.

Clearly, this conflict has led us into hysteria. Sanctions seem to have become the preferred tool of our foreign policies. If we had insisted that Ukraine abide by the Minsk agreements, which we had negotiated and endorsed, none of this would have happened.

Vladimir Putin’s condemnation is also ours. There is no point in whining afterwards – we should have acted earlier. However, neither Emmanuel Macron (as guarantor and member of the UN security council), nor Olaf Scholz, nor Volodymyr Zelensky have respected their commitments. In the end, the real defeat is that of those who have no voice.

The European Union was unable to promote the implementation of the Minsk agreements – on the contrary, it did not react when Ukraine was bombing its own population in the Donbass. Had it done so, Vladimir Putin would not have needed to react. Absent from the diplomatic phase, the EU distinguished itself by fueling the conflict.

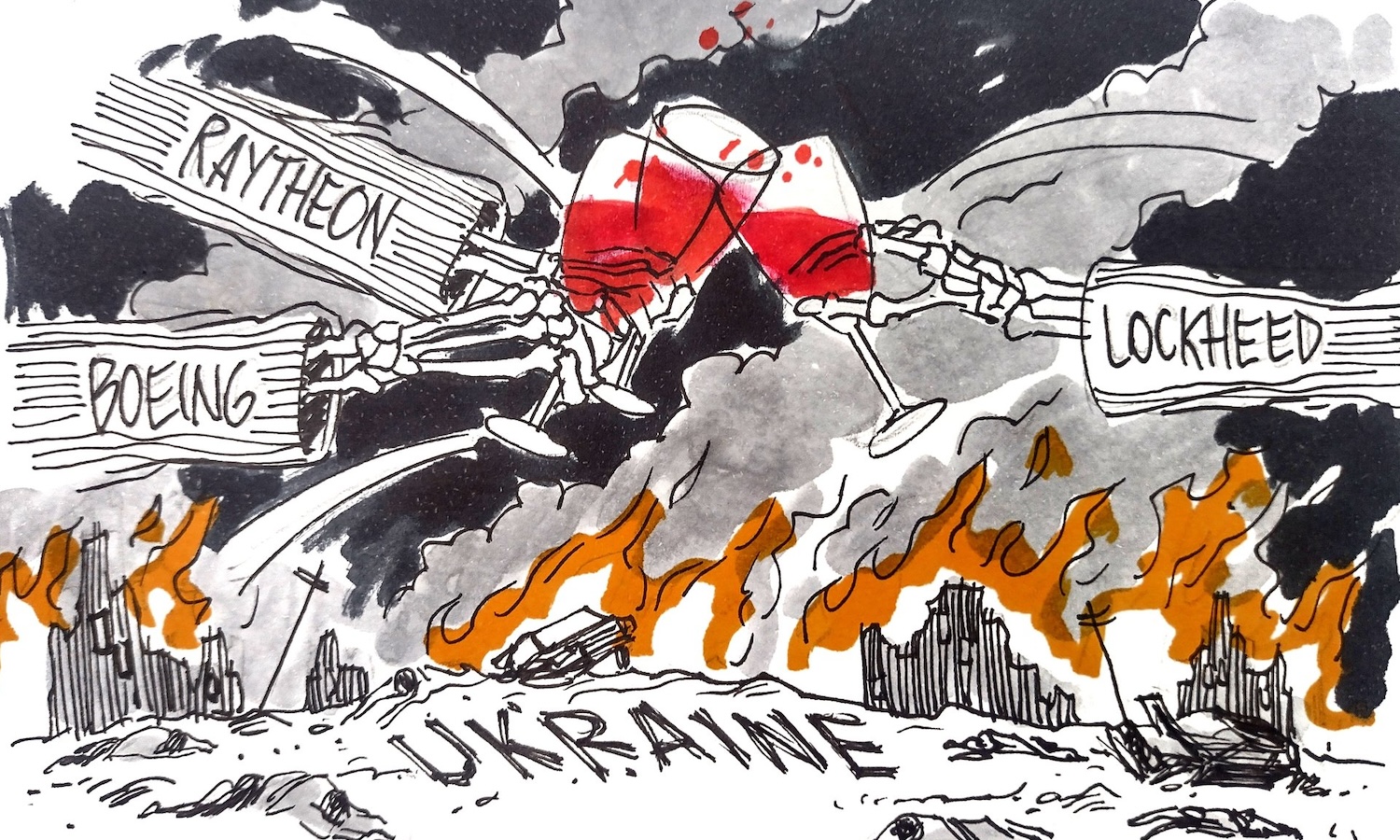

On 27 February, the Ukrainian government agreed to enter into negotiations with Russia. But a few hours later, the European Union voted a budget of €450m to supply arms to the Ukraine, adding fuel to the fire. From then on, the Ukrainians felt that they did not need to reach an agreement. The resistance of the Azov militia in Mariupol even led to a boost of €500m for weapons.

In Ukraine, with the blessing of the western countries, those who are in favour of a negotiation have been eliminated. This is the case of Denis Kireyev, one of the Ukrainian negotiators, assassinated on 5 March by the Ukrainian secret service (SBU) because he was too favorable to Russia and was considered a traitor. The same fate befell Dmitry Demyanenko, former deputy head of the SBU’s main directorate for Kiev and its region, who was assassinated on 10 March because he was too favorable to an agreement with Russia – he was shot by the Mirotvorets (‘Peacemaker’) militia.

This militia is associated with the Mirotvorets website, which lists the “enemies of Ukraine”, with their personal data, addresses and telephone numbers, so that they can be harassed or even eliminated – a practice that is punishable in many countries, but not in Ukraine. The UN and some European countries have demanded the closure of this site – refused by the Rada.

In the end, the price will be high, but Vladimir Putin will likely achieve the goals he set for himself. His ties with Beijing have solidified. China is emerging as a mediator in the conflict, while Switzerland is joining the list of Russia’s enemies. The Americans have to ask Venezuela and Iran for oil to get out of the energy impasse they have put themselves in – Juan Guaidó is leaving the scene for good and the United States has to piteously backtrack on the sanctions imposed on its enemies.

Western ministers who seek to collapse the Russian economy and make the Russian people suffer, or even call for the assassination of Putin, show (even if they have partially reversed the form of their words, but not the substance!) that our leaders are no better than those we hate – for sanctioning Russian athletes in the Paralympic Games or Russian artists has nothing to do with fighting Putin.

Thus, we recognise that Russia is a democracy since we consider that the Russian people are responsible for the war. If this is not the case, then why do we seek to punish a whole population for the fault of one? Let us remember that collective punishment is forbidden by the Geneva conventions.

The lesson to be learned from this conflict is our sense of variable geometric humanity. If we cared so much about peace and Ukraine, why didn’t we encourage Ukraine to respect the agreements it had signed and that the members of the security council had approved?

The integrity of the media is measured by their willingness to work within the terms of the Munich charter. They succeeded in propagating hatred of the Chinese during the Covid crisis and their polarised message leads to the same effects against the Russians. Journalism is becoming more and more unprofessional and militant.

As Goethe said: “The greater the light, the darker the shadow.” The more the sanctions against Russia are disproportionate, the more the cases where we have done nothing highlight our racism and servility. Why have no western politicians reacted to the strikes against the civilian population of Donbass for eight years?

Because finally, what makes the conflict in Ukraine more blameworthy than the war in Iraq, Afghanistan or Libya? What sanctions have we adopted against those who deliberately lied to the international community in order to wage unjust, unjustified and murderous wars?

Have we sought to ‘make the American people suffer’ for lying to us (because they are a democracy!) before the war in Iraq? Have we adopted a single sanction against the countries, companies or politicians who are supplying weapons to the conflict in Yemen, considered to be the ‘worst humanitarian disaster in the world‘? Have we sanctioned the countries of the European Union that practice the most abject torture on their territory for the benefit of the United States?

To ask the question is to answer it … and the answer is not pretty.

______________________________