Is Britain rich? Taking gross domestic product (GDP) from 2021 as a measure of a country’s wealth, Britain is sixth in the world rankings. If we take gross national income (GNI) as the measure, Britain is the 23rd-richest in the world. Pretty wealthy!

Then why is it that, as of 2021, after housing costs are taken into consideration (a consideration that has more and more impact as this cost rises), 3.9 million (27 percent) of Britain’s children live in poverty? (See Table 1.4b from Households below average income report for financial years ending 1995 to 2021, Department for Work and Pensions, 31 March 2022)

There is plenty of wealth in Britain’s economy, but it isn’t reaching masses of workers, or their children. With food bank usage on the rise, the number of workers unable to meet mounting housing and energy costs, we are now witnessing the growing phenomenon of children trying to gain an education while hunger gnaws at their insides.

Learning to be hungry

According to the Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG) 800,000 children in England live in households that qualify for universal credit but miss out on free school meals. A family on universal credit must earn less than £7,400 a year (£617 a month), excluding their meagre ‘benefits’ to qualify for a free meal.

Moreover, and quite ludicrously, this rule doesn’t consider the number of children a low-income family is trying to provide for. Many children in poverty simply don’t qualify for free school meals provision.

This leads to children arriving in school hungry – so hungry that they are eating rubbers or hiding in the playground because they can’t afford lunch, pretending to eat from empty lunchboxes to hide their poverty from friends. To try and feed themselves, pupils are cleaning the canteen to earn food (!) and, according to reports from headteachers across England, stealing.

A CPAG spokesman said: “This low threshold means that many children from working families in poverty aren’t entitled to free school meals, despite their parents being unable to meet the costs of food.”

The repercussions don’t just stop at a lack of focus in class, they extend to every part of life. An assistant secondary headteacher in south London told the Evening Standard of the lengths some pupils are driven to:

“Students stealing food has grown to around 15 incidents a day. Typically, they take a drink or several cookies, usually something with high sugar content. I challenged a kid once and he looked like he was going to cry. Now I turn a blind eye.

“They are taking a big risk because to be caught in front of your peers is humiliating. Around 30 percent of our students get free school meals, but a further 50 percent are in poverty but miss out. They are the ones I worry about.”

She added: “You feel those kids who steal are desperate and haven’t eaten since the night before. I regularly observe students, including our prefects, taking on jobs cleaning the canteen so they can be allowed a free meal at the end of lunch by the catering staff.

“It’s outrageous that children should have to do this. People outside schools have no idea how bad things are, and in my 28 years in this profession, it’s never been as bad as it is now.”

This desperation isn’t confined to the pupils; parents are also resorting to stealing or drug dealing to feed their children. (Stealing to eat: Hunger crisis for children not eligible for free school meals but living in poverty by David Cohen, 10 October 2022)

The Evening Standard article continues by quoting 23-year-old Ellie Williamson, a youth worker from Lives Not Knives who supports children at schools in Croydon who highlights one young person’s struggle:

“Take Anton. He is 14. He doesn’t get free school meals because his single mother earns above the threshold, but the cooker doesn’t work at home and if his nan can’t give him pennies, he’s going hungry.

“I have seen him go from a lovely, balanced and respectful young man to being obsessed about money. It’s led to him stealing and taking big risks with his future. I read him the riot act but he turned to me angrily and said: ‘I’m not stupid, I know what I’m doing.’ Then he started crying. He knew I was right.

“He was trying to weigh up his options and he said: ‘But if I do it your way, I won’t have money for food or things, so what must I do?’ It broke my heart. He’s concluded, age 14, that food is not guaranteed for him — that he has to turn to crime to eat.”

A right to free education?

People in Britain are allowed the right to a free education. But what is a right if it cannot be exercised owing to a lack of funds? You can walk through those doors for free, yet dozens of small economic barriers either limit, or even exclude, poor workers from accessing what’s available inside.

Not being able to afford sufficient food to maintain concentration; the correct clothing to be allowed access to school grounds; easy access to computers and the internet to keep up with homework or fill a young, inquiring mind … And, of course, poverty brings worries about homelessness and family strife, alongside parents without time or education to supplement learning at home.

All these present serious barriers to being able to fully grasp the ‘right’ to an education.

And this is before pupils even sit down in front of a teacher (many of whom are facing the same issues) in an oversubscribed class to try and make sense of the world and prepare for a future that isn’t theirs.

This author was informed by one such pupil that they were made to remove a non-approved sweater and so sat shivering in an unheated classroom – unheated owing to the school’s inability to meet soaring energy costs. Approved uniform is sometimes only available from an approved vender, which can charge as it pleases thanks to their school-granted monopoly status.

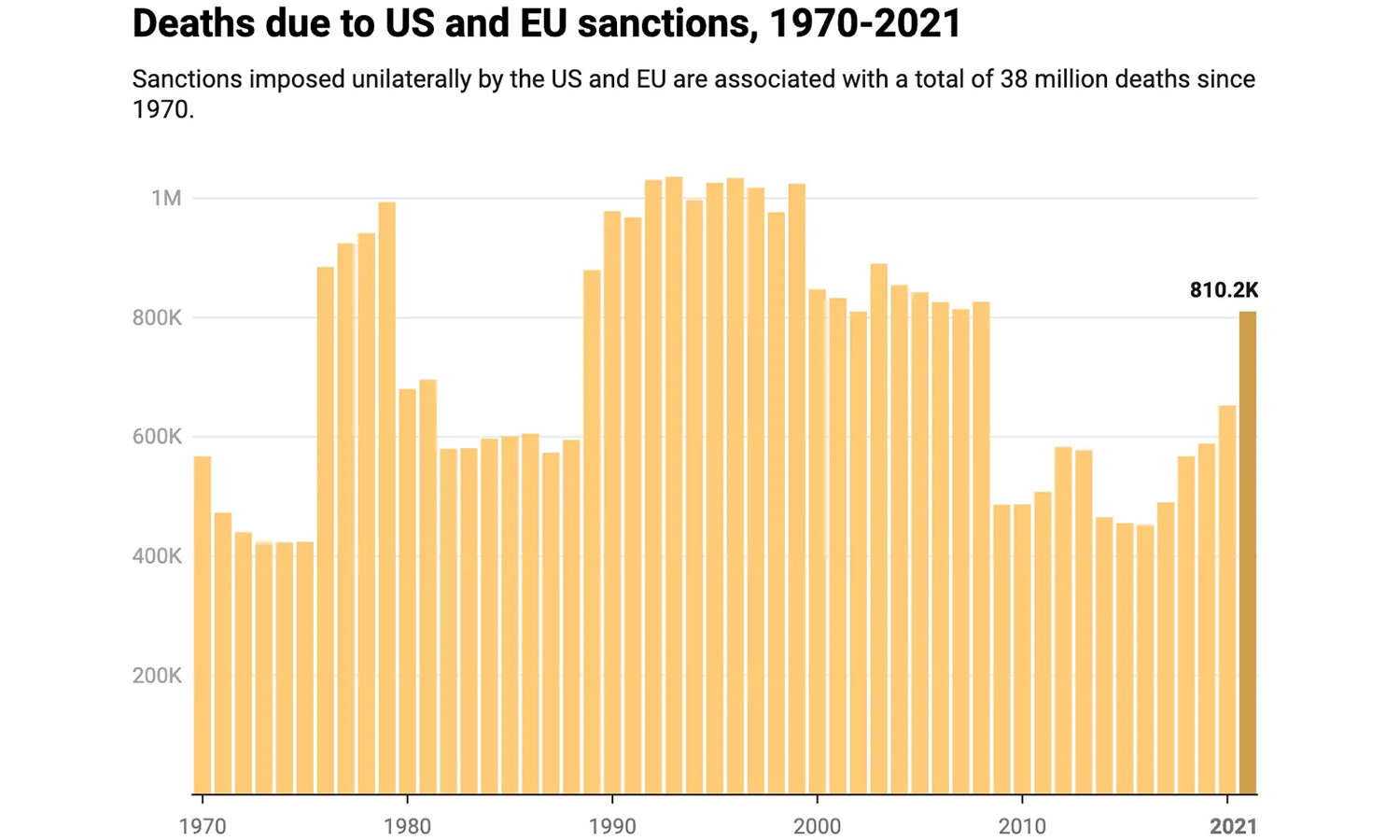

Children are often punished or excluded for not having this mandated clothing – clothing that is simply unaffordable for many workers. These punishments are obscured under the term ‘sanctions’ – a term that is normally reserved for use by the DWP to deny workers much-needed financial support, or by imperialists to obscure economic warfare.

What place has such an ethos and such language in a school? If we say that such an environment is more likely to prepare young working-class children for the scrap-heap of unemployment than for a useful and meaningful life in which they can contribute to the development of society – are we exaggerating?

All these thousand cuts – hunger, cold, worry, social stigma and more – are impacting the ability of our young people to learn, fuelling the cycle of undereducation arising from poverty rather than from any lack of intelligence or desire to learn.

Misspending and penny-pinching

As our education system becomes increasingly privatised, schools are becoming cash cows for private capital.

To take just one example, a school will tender private firms to provide inadequate meals that cost the taxpayer a premium. Some schools, or should we say the companies that schools pay, provide a single slice of pizza or a small polystyrene cup of pasta and a blob of tomato sauce. Whatever isn’t spent on food and wages by these companies goes to increase their profit margins.

Another example of this profiteering from poverty was the pitiful ‘food parcel’ scheme provided in the school holidays of 2021, which was only exposed as such as a result of the massive public outcry. In that instance, the government ended up paying companies to supply food worth £30, yet the firms concerned only provided around £5 worth.

That ‘bounty’ was expected to provide the equivalent of school dinners for a week. Pocketing the difference, the companies trusted with our tax money walked off with a huge profit.

Meanwhile, some parents said they received a pot of flour and instructions on how to bake eight bread rolls in a food parcel. The intention, according to Impact Food Group was to help parents create “an interactive cooking experience” with their children, and to help with some food education at home. Apparently education is now the focus?

“It’s very humiliating,” one parent said. “Why would you decide for us? Why not give us the money?” The argument often given is that money won’t be spent on food. As if a parent wouldn’t automatically feed their child.

As if those children and their parents forced to resort to crime to get the money for food are showing their true characters. As if the crimes were, in fact, the end, and not merely the only available means to feed the hungry.

This is how our government sees workers. Truly they believe in Victorian values.

Instead of seeing a victim of a system that cannot meet its people’s basic needs, poor children and their parents are viewed as being responsible for their unenviable situation – responsible for the crime of not being able to tame market forces or rein in the unfeeling stampede of profit-driven production.

Bourgeois economic ‘experts’ with a comfy lifestyle, decades of economic education under their belts and hands firmly grasping the levers of the economy, fail to wrestle with that beast daily. How can a Mum or Dad, working multiple jobs on insufficient sleep and food, expect to do something that someone with all the resources and know-how can’t?

Profiteering in schools

According to the Food Contract Manufacturing Global Market Report (2022) published by The Business Research Company, the size of the global food contract manufacturing market is expected to grow from $126.82bn in 2021 to $141.62bn in 2022, at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.7 percent. By 2026, the market for meal provision is expected to grow to $207.79bn – an annual growth rate of 10.1 percent.

One large company that is commissioned to provide school meals in Britain is Sodexo, whose turnover grew from £1.19bn to £1.36bn between 2020 and 2021 (a 15 percent increase) and whose profits increased 200 percent from £16.5m to £45.7m.

As more and more capitalists smell profit in this sector, there will be a race to the bottom as wages are slashed and the service (in this case, food provided to schoolchildren) is reduced in amount and quality in order to maintain these profits.

Schools are tax funded, which allows companies to secure long-term contracts at incredibly generous (to them, not the taxpayer) terms. If the services are inadequate, the government is pressured to increase funding to those sectors, thus fuelling further shareholder bonanzas.

A better way

Food, like affordable housing, access to warmth, water and power, is a basic need, essential to workers’ survival. The poverty that leads workers to rely on handouts – handouts that become an avenue of further profiteering to our ruling class, the capitalists – shouldn’t exist in a country that has an industrial and agricultural base like Britain’s.

With our factories and fields taken into ownership by workers, organised in such a way that the resultant surplus can be distributed and reinvested in a scientifically planned manner, our country would not only be able to increase its productive capacity, but our production would be directed to meet the needs and interests of the working people, with better welfare support systems and higher consumption by the people who create this abundance – all without the need for exploitation.

We can, and we must, do away with capitalist anarchy of production, the boom-and-bust cycles that leave increasing numbers of workers unemployed, underpaid, over-exploited, insecure and empty-bellied.

Socialism will pave the way for all our children to achieve the highest levels of culture, productivity and education, thanks to the way our collective work for the benefit of society and production will be organised – allowing the fruits of workers’ labour to satisfy workers’ needs, first and foremost.

While we allow capitalism to reign, the reverse will always be the case: the fruits of our collective labour, privately appropriated, will remain the very means the billionaire class uses to exploit and oppress us further.