Harpal Singh Brar died at 10.10am Indian time (4.40am UK time) on 25 January 2025, at 85 years of age. He was at the home of his nephew Manpreet Singh Badal, in Chandigarh, India. His close comrade and leader of the CPGB-ML Ella Rule, as well as his daughter Joti, and sons Ranjeet and Carlos were with him. He leaves us bowed in grief. But we are grateful to have been part of his deeply meaningful life and work. Truly we can say that he shed light on our path. And that the struggle to which he dedicated his life will continue.

Harpal was cremated the same evening, in his ancestral village and the place of his birth, Fattanwala, near the town of Muktsar, in the state of Punjab. The entire village and many people from surrounding villages and towns attended, as did many members of Harpal’s Punjabi family and contacts from his original life. It is hard to think of him as a horse-riding, crop-raising Punjabi farmer, but those were his roots before he journeyed to the metropolis to study for a master’s degree in law at University College London, where he would meet and marry his wife, Maysel Kathleen Sharp, become a communist, find his lifelong friends and comrades and discover his true calling – to work for the liberation of mankind.

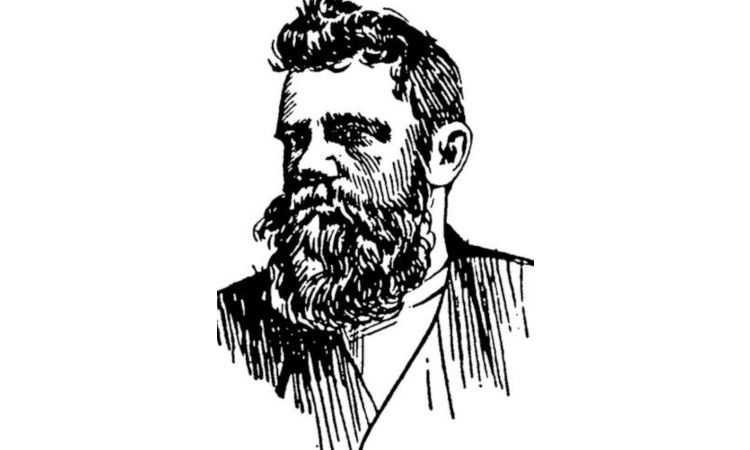

Harpal was a beautiful human being, loved by those who knew him and particularly by all who shared his struggle and his cause. He was a passionate, charming and charismatic man, full of generosity, humour and joy, with great loyalty and affection for his comrades, friends and family, and a deep love for the working masses. Harpal was a fiery and powerful orator, who both educated and raised the temper of his audience, and hundreds of workers and revolutionaries were drawn to his leadership.

His uncompromising and principled positions, his loyalty to the cause of the working and oppressed masses, won him firm friends and comrades. By the same token, these very attributes aroused the hostility of the oppressing class and the reactionary political and academic cheerleaders of empire colonialism and imperialism, as well as their political representatives in the working-class movement. Harpal was fearless in speaking out against the Labour party social democrats and reformists, opportunists and Trotskyites, pacifists, anarchists, bourgeois nationalists (including sikh Punjabi ‘nationalists’ of the ‘Khalistani’ movement) and black separatists, whose political ideas he criticised and organisations he exposed as being vehicles for misleading the workers.

Following Lenin, Harpal believed and taught us that a revolutionary must be firm in principle, flexible in tactics, and strong enough to swim against the current of ‘accepted’, ‘allowable’ and ‘fashionable’ opinion set by the bourgeoisie and its spokesmen. All who stand for the interests of the working class against the powerful apparatus of imperialism must be able to “hear the sound of approbation, not in the dulcet sound of praise, but in the roar of irritation!”

Harpal was self-deprecating about his intellectual abilities and achievements, putting down his great erudition to steady and continual “hum-drum, everyday” study and work, but he was undoubtedly exceptionally able and bright, and his journey from rural Punjab to London, the city at the centre of the British empire where he threw in his lot with the struggle of the revolutionary proletariat, is a remarkable one.

Fattanwala

Harpal was born and raised in colonial India, into a sikh family whose parents were of the landed peasantry. Indeed, he was a direct descendant of Fattan Singh, the village founder, and his ancestors were horse traders and farmers. The India of his birth was ruled by the British Raj, which had systematically “bled” (in the words of Lord Salisbury) the peoples of the subcontinent to amass great wealth in England, and the British colonists lived in great opulence and parasitic splendour in the decaying days of empire, behind the ‘civil lines’ and in their racially exclusive clubs.

The British had raised millions of pounds to fund the world war through taxation of the impoverished Indian masses and levied some 1.3 million soldiers from India (over a million of them from Punjab) to fight for the ‘motherland’ in WW1 and 2.5 million in WW2. Harpal never had any direct contact with the colonial rulers, yet their policy would rend his world. Fattanwala village was at the centre of pre-Partition Punjab, close to Lahore and now just south of the India-Pakistan border.

There was no systematic schooling of the Indian masses at the time of his birth. The British colonial regime had suppressed pre-existing Punjabi-medium schooling, which had been highly advanced in Ranjit Singh’s independent and religiously pluralistic Punjabi kingdom, and had not replaced it with any widespread substitute. Being a majority muslim village, the local primary education was in the madrassa, supervised by the village maulvi – the local muslim religious scholar and teacher – and it was here that Harpal had his first education, and learned to pen his name in the Punjabi language written in the Arabic script.

In 1947, a young Harpal witnessed the cataclysmic partition of India, with its accompanying communal riots and pogroms. At seven years of age, he had not yet learned or understood that this was a plan of the imperial British ruling class, in its decline and upon quitting India, to engender animosity, weakness and lasting division among the peoples of the subcontinent. He had not learned of the role of Shaheed Bhagat Singh in raising a revolutionary movement for hindu-muslim brotherhood, independence and socialism in India – though as an adult he would rediscover this history and write his beautiful work Inquilab Zindabad!, documenting India’s freedom struggle.

Yet that great historical tragedy that he witnessed had a lasting impact upon him. Perhaps about Harpal, too, we can say, with Marx and Engels, that what the bourgeoisie produces above all else are its own gravediggers. [1]

Harpal’s father Harchand Singh Brar, with his grandfather, spent many nights patrolling on horseback with guns in hand, to protect their muslim friends and neighbours from the communal violence that accompanied Partition. They honoured their commitment to locate and communicate with their divided friends and where possible to send resources across the ‘Radcliffe Line’ – the new border, brought into being by Lord Mountbatten under the orders of the postwar Labour government of Clement Attlee.

Prior to Partition, his best friend had been a muslim boy, from whom he was separated, and the character of his village and life was changed forever. Harpal always considered that the people of India and Pakistan were one people and were better off united. Indeed, he came to understand that the workers of all countries must unite if we are to rid society of its many injustices, national and religious prejudices.

It takes a village to raise a child. And while in the village as a boy, Harpal would play from sunup to sundown, in the fields, streets and houses of friends and relatives, eating and laying his head in whichever home he happened to find himself. Being a sociable and inquisitive boy, with an incredible memory for detail, Harpal had many stories from his youth, whether witnessing the fights over blood feuds and land disputes fought among the Punjabi peasantry (even as a child he realised their futility and stupidity), of riding to the local towns on horseback with his grandfather, taming stallions, or running up bills taking friends to Muktsar’s dhabas (tea shops) – to his father’s great annoyance! As a school for an orator, the village was hard to beat, and he derived lifelong strength from the peasantry – its folklore, sayings, jokes and rustic optimism.

He was among the first to see a tractor brought to his village and witness the scepticism of the peasantry turn to amazement and joy as it ploughed more acreage in a day than a team of oxen could previously have ploughed in a week. He witnessed the introduction and motorisation of tube wells and the greening and reclamation of semi-arid land. The impact of mechanisation and the application of technology to agriculture were a matter of practical and lasting significance for him – and for us all.

Harpal’s connection to the peasantry, and his childhood experience, stayed with him when he would later consider the agricultural revolution in the USSR and learn about collectivisation and the socialist solution of the peasant question – holding the key not only to the successful revolutionary struggle of the masses, but to raising productivity, feeding the growing towns and cities, and delivering the mass of humanity from poverty and ignorance.

Muktsar

Harpal was sent to board at the Khalsa (sikh religious) school in the local town of Muktsar (founded where the tenth sikh guru, Gobind Singh, had fought his last great battle), and there, despite the odds – and once burning down the dormitory in a game of ‘pistols’, in which the boys fired phosphorous-tipped matches at each other! – he learned Hindi and English, and gained a love for the humanities and current affairs.

It was the fashion among his peers not to study, but to sleep late, wake late and do the minimum. But gaining a genuine interest and thirst for knowledge that would last throughout his life, Harpal would wake early, go to the fields with his books and the newspapers, and study before his friends awoke. When his exam results came, and he had excelled in them all, he simply claimed that there must have been a mix-up with the exam papers.

After secondary school examinations, he gained entry to university in Chandigarh, where he studied English, Punjabi and History, and after gaining his Bachelor of Arts degree, he accepted a place at Delhi University to study for a bachelor’s degree in law.

Delhi

It was while studying in Delhi that Harpal attended his first political demonstrations, held to protest the assassination (by the colonial powers of Belgium, France and the USA) of Patrice Lumumba, newly independent Congo’s heroic anti-imperialist leader, and in support of the great anti-imperialist struggle of the Vietnamese people and of their leader Ho Chi Minh, who would famously write that “Nothing is more precious than independence and freedom!”

These would be the first of hundreds of demonstrations, meetings and actions that Harpal would participate in, speak at and lead.

England

Drawn by his enquiring mind and driven by his energetic spirit, Harpal decided that he would travel to England to study for a master’s degree in law. He gained entry to London’s University College and arrived in the summer of 1962, just ahead of the enactment of the UK’s first anti-immigration legislation that affected Commonwealth citizens. Harpal always remembered that his first actions on arrival were to buy a coat – he found it incredibly cold – and to cut his hair, an act symbolic of moving from a culturally religious upbringing to the materialist outlook of his conscious maturity.

In later life, Harpal would never shy away from the discussion of religion with anyone who professed faith, saying that he had seen the most heinous acts carried out in the name of religion – referring to the communalism that the British and the postcolonial ruling classes of the subcontinent used to keep the masses of India and Pakistan in subjection, and against which Harpal was a lifelong campaigner. He recommended Bhagat Singh’s Why I am an atheist, as well as the dialectical materialist teachings of Marx and his followers.

London was a hard city to acclimatise to, climactically and culturally, and at first it was more his pride than any love for the strange and unwelcoming environment that kept him there. Yet, little by little he was absorbed into its life and, despite the fact that (as he often said in speeches) “immigrants don’t come here for the warm reception, the warm weather or the great food!”, he was to make his closest personal friends, and his most loyal and faithful comrades, amongst the British working class.

While a student, two things happened to Harpal that changed his life forever, to the consternation of his father (who had wanted him to return to India and marry into a wealthy Punjabi family), but to his and our great benefit.

First: he found Lenin in a Luton library.

Harpal used to tell us that soon after arriving from India, before starting his course and while searching for work, he picked up a book and read, by chance, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov Lenin’s words. The volume he selected contained Lenin’s appeal to a party tribunal, before which he had been arraigned by the Mensheviks for issuing a pamphlet against their factional activities and compromises with the reactionaries on the eve of the elections to the second Duma. [2]

Harpal was riveted by the power and incisive logic of Lenin’s arguments. So captivating were Lenin’s words and thought, so vividly did they imprint themselves upon him with the justice of the Bolshevik cause, that he was compelled to read more.

There started a lifelong relationship that led Harpal to embrace revolutionary Marxism-Leninism as the solution to the problems faced by humanity. He would go on to read every word of Lenin’s writings and become a firm Leninist and Marxist. It is not without reason that Lenin’s writings are no longer stocked in Britain’s public libraries!

Second: he fell in love with and married a fellow student, studying for her bachelor’s degree in law, Maysel Kathleen Sharp.

Together they became increasingly involved in the anti-imperialist, working-class and communist movement. They studied and discussed the revolutions of Russia and China, the economics of capitalism and socialism, the works of Marx and Engels, Lenin and Stalin, Mao Zedong and Ho Chi Minh.

In the wake of the Cuban revolution and the ‘Cuban missile crisis’, when masses of workers had been shaken by the possibility of nuclear war, yet the triumphant march of humanity toward socialism seemed not only inevitable but immanent, they immersed themselves in the revolutionary and anti-capitalist struggles among Britain’s students and workers.

Great October Socialist Revolution

Harpal visited the USSR in 1963 and was greatly impressed with the fruits of Soviet democracy and socialist society. He became a passionate advocate of the Russian and Chinese socialist revolutions and peoples, and the anticolonial struggles of the Vietnamese people, the South African and Zimbabwean people, the Korean and Palestinian people, and a host of other liberation and anticolonial movements struggling against British, US, French, Belgian and European imperialism.

The struggle of the colonies and neocolonies for their freedom were inextricably linked with the struggle of the working class for socialism. “Workers of all countries, unite!” was the slogan that he accepted and adopted from Marx and Engels’ epoch-making work The Communist Manifesto, and which guided his activity.

Harpal became a staunch internationalist, realising that just as accumulated capital had transcended and overflowed national limits, scouring the globe for workers, resources and markets to exploit; just as peoples in all corners of the world had been displaced from their native soil by impoverishment, upheaval and colonial war, and drawn to seek their living in the imperialist nations, so the workers must learn to put aside national differences and cooperate together in their common struggle against capitalism.

Harpal was inspired by Lenin’s words at the second congress of the Communist International: “Communist parties and groups in the east, in the colonial and backward countries, which are so brutally robbed, oppressed and enslaved by the ‘civilised’ league of predatory nations, were likewise represented at the congress. The revolutionary movement in the advanced countries would in fact be nothing but a sheer fraud if, in their struggle against capital, the workers of Europe and America were not closely and completely united with the hundreds upon hundreds of millions of ‘colonial’ slaves, who are oppressed by that capital.” [3]

Capitalism could not be reformed, he realised. It must be overthrown. Society could only move forward on the basis of a new and higher democracy; a Soviet democracy, that would put the socially-operated productive forces (currently individually owned by the billionaire elite) on a firm basis of social ownership, eliminating exploitation and all its accompanying ills. Together, Harpal and Maysel resolved to dedicate their lives to the cause of communism.

The ‘fissiparous’ communist movement in the aftermath of Khrushchev and the Sino-Soviet split

Encountering ‘opposition’ movements within the students’, women’s and communist circles, and growing denunciations of Stalin amongst the Trotskyites in particular, Harpal and Maysel turned to study these questions for themselves, reading both Stalin and Trotsky, studying the disputed issues, and adjudicating firmly in favour of the revolutionary line of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks) and Comintern under the leadership of Josef Vissarionovich Stalin.

Harpal and Maysel were active in the anti-imperialist movement in the Britain Vietnam Solidarity Front, and became ever more determined to forge an organisation dedicated to freeing humanity of its historical burden of exploitation. Harpal spent an increasing amount of his energy studying the reality of the social, economic and political conditions in Britain, and organising to change them for the better. They joined the Revolutionary Marxist-Leninist League (RMLL) led by Abhimanyu Manchanda, a prominent anti-revisionist communist who had been the partner of legendary west Indian, American and British communist leader Claudia Jones – the founder of the Notting Hill Carnival and the West Indian Gazette, among other achievements.

Harpal and his comrades played a major role in the British anti-Vietnam war movement, and led demonstrations in 1968, leading the protestors to the US embassy in Grosvenor Square, while the Trotskyites of the International Marxist Group (led by Tariq Ali, in fact) tried to lead the protest to disperse harmlessly in Hyde Park. Harpal led the demonstrators to go beyond the pacifist slogan of ‘peace’, to call for the victory of the Vietnamese people, who were led in the US-occupied south by the National Liberation Front and in the north by such legends as Vo Nguyen Giap and Ho Chi Minh.

Harpal was marked by the police as a “charismatic, persuasive and dangerous speaker, capable of leading the crowd” from that day forward, but never did it stop him organising and living his life to the full. He was never impressed or intimidated by petty police spies, or by the threats and intimidation of his class enemies.

Inspired by the triumphant Chinese people’s revolution led by Mao Zedong, and by the strides it was taking to build socialism and combat revisionism (that is, the economic reintroduction of capitalist economics within the USSR that was already well underway by the early 1960s), Harpal and Maysel took a ‘Maoist’ anti-revisionist line, and adopted many key positions that Harpal would later expand upon and defend. This experience also reinforced the idea that there could be no revolutionary movement without a revolutionary theory; that study of revolutionary theory was essential to guide the movement, and that without serious ideological leadership, the cause of the liberation of the working class would flounder. [4]

We only recently learned that Harpal and Manchanda briefly joined the CPBML (which exists in a much diminished form today) and were on its central committee alongside its leader Reg Birch, before deciding that its economism and narrow nationalism were leading it toward oblivion.

Falling foul of Manchanda’s notorious sectarianism, he and Maysel were expelled from the RMLL. However, before Manchanda died in 1985, he and Harpal were reconciled and became good friends.

Although he agreed with the Communist Party of China’s critique of Khrushchevite revisionism, Harpal came to realise that the Chinese line which denounced the Soviet Union as “social imperialist” was wrong and harmful, despite the incorrect capitalist-roading policies of the USSR.

Association of Communist Workers

Harpal and Maysel met their lifelong companions, friends and comrades Iris Sloley and her partner and later husband Godfrey Cremer at a national meeting of the women’s liberation movement in 1970, and soon afterwards they met Ella Rule, now chair of the CPGB-ML. These comrades were to become the core of the anti-revisionist Association of Communist Workers (ACW).

They were active in the movement, arguing against bourgeois feminism and for a revolutionary programme of equality for women as part of the working class’s movement for socialism. They formed the Union of Women for Liberation, vociferously fought the pernicious ideas of Germaine Greer, of Selma James’s ‘Wages for Housework’ and their ilk, and the ideas that ‘bra burning’ or ‘kicking the oppressor (men) out of your bed’ would somehow equate to equality. Their work together forged a bond of loyal comradeship that lasted a lifetime and would form the basis of the work Marxism and the Emancipation of Women.

They concluded early in the course of their study and activity that the Labour party was a party of imperialism. A social-democratic party: socialist in words (more so then than now), but chauvinist, imperialist, capitalist in its programme and deeds, whether in power or acting as a loyal parliamentary opposition.

Because the disintegrating Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), Britain’s original Communist party established in 1920, was now, under the influence of Khrushchevism, firmly ‘revisionist’, having turned its back on the need for workers to overthrow the capitalist ruling class’s state machine (as taught by Marx) in favour of a ‘parliamentary road to socialism’, wedded to a policy of supporting the imperialist Labour party, these comrades could not join it. In Harpal’s own words: “What would be the point of joining such a party, only to be expelled from it?” The CPGB slid all the way to the bottom of this revisionist slope and, in 1991 when the USSR collapsed, its Eurocommunist leadership simply declared that “The October Revolution was a mistake of historic proportions” and, to the disgust of its remaining proletarian members, dissolved itself.

Former members of the CPGB had formed the Communist Party of Britain (CPB) in 1988 as the CPGB leadership was moving too far to the right. The New Communist Party (NCP) had earlier split from the CPGB when the latter adopted Eurocommunism – criticising the Soviet Union from the right, denouncing its intervention in the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and the 1968 Prague Spring. Nevertheless, both the CPB and NCP essentially adopted – and maintain to this day – the CPGB’s revisionist programme of the parliamentary road, which has left them tailing Labour to irrelevance.

The ACW campaigned to persuade the leadership of these parties to give up their position of support for the imperialist Labour party – but both proved incapable of doing so, and could not therefore take the communist movement forward.

Hemel Hempstead, Harrow and Southall

Passing the Bar exam to become a barrister, Harpal did not choose to practise, but instead taught law, first at Dacorum College in Hemel Hempstead, where he settled with Maysel, and then at Harrow College of Further and Higher Education, which later became part of the University of Westminster. Teaching was merely a means to an end, however, and Harpal’s real passion and unflagging energy were reserved for his political work.

Harpal demonstrated a clarity of thought and analysis that helped him to guide his comrades, and by degrees he became a socialist and communist teacher, a writer, a political theorist and a practical working-class political leader and organiser.

It is a little-known footnote to the history of Hemel Hempstead that Harpal and Maysel were visited by many revolutionaries and communists in their home, among them Robert and Sally Mugabe in the summer of 1974, then the leaders in exile of the Zimbabwean national-liberation struggle against the British colonialists and the Ian Smith (Rhodesian) apartheid regime. Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (Zanu-PF) was the political leadership of the armed struggle of the black masses for their freedom, and Harpal edited a solidarity journal entitled Revolutionary Zimbabwe for the British anti-apartheid movement (Zimbabwe Solidarity Front) that was distributed to and read by the activists and soldiers of Zanu and Zanla (Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army).

Harpal would later interview Robert Mugabe at several crucial junctures in his negotiations with the British for independence, and when apartheid was overthrown and elections were held after the Lancaster House agreement, Harpal was invited to attend the independence celebrations in Harare by President Mugabe. Harpal had no money for the plane ticket, but his comrades insisted he attend and raised the money to send him.

Reaching the airport with his invitation and no directions, he hitched a ride on the back of a worker’s pickup truck to the presidential palace, and approached the armed guards at the gate, unsure of gaining admission. Diplomatic cars and the great and the good were passing into the compound through the security cordon. When challenged, Harpal presented his invitation, whereupon the armed Zanla soldier of the presidential guard took off his machine-gun, placed it on the ground and embraced him as a brother, saying: “Comrade Brar! Welcome!”

Standing in line to be welcomed by the president, he was met with warm comradely enthusiasm. Sally turned to Robert and said “Robert, you should hear him speak! He is pure fire!” To which Mugabe replied: “I know, I have heard him!” A great music concert was held that evening, at which Bob Marley sang his anthem dedicated to the liberation struggle, simply entitled ‘Zimbabwe’.

Their mass work among British and Indian workers was guided by deep study and writing. Harpal found in Ella, Iris, Godfrey and Maysel great comrades and companions, and Comrade Ella became his closest intellectual collaborator. In many ways, Harpal’s work was also Ella’s, and vice versa. It was Ella, Godfrey and Iris who would give him feedback – and who typed the articles that Harpal would always write longhand, with paper and pen. Harpal in turn was a constant source of support, advice and knowledge for them.

Indian Workers Association and Lalkar

Harpal and his comrades of the ACW became actively involved with the Indian Workers Association (GB), which struggled for the civil rights of Indians and all immigrant workers in Britain. The organisation was a leading voice in the fight against racism, which Harpal rightly perceived to be the Achilles’ heel of the British working-class movement – a mechanism for dividing, weakening and therefore controlling white as well as black workers.

Becoming one of the IWA’s leading organisers in Southall, the home of the Punjabi community in Britain, he was also the editor of the IWA’s newspaper Lalkar, which he refounded and edited from its first issue in 1979 until his death.

Lalkar is a Punjabi, Urdu and Hindi word meaning ‘militant challenge’, and it also contains the roots of the words lal meaning red and kar meaning work. Though the paper was separated from the IWA as the latter itself wound down its activity, it remains a great source of revolutionary analysis and Marxist teaching, and it continued to appear as an independent anti-imperialist theoretical journal throughout Harpal’s lifetime. Under his editorial leadership, Lalkar was a beacon of clarity not only for Indian workers in Britain but for the entire progressive British and international working class. Indeed, for the January 2025 issue, Harpal wrote four articles and put the paper to the printers, before succumbing to his final illness.

In the job of writing for, producing and distributing Lalkar, his comrades from the ACW were close collaborators. In a very real sense, they were at the political heart of the Indian Workers’ Association, and lived and struggled closely with the Indian workers of Britain. His comrades are committed to continuing and augmenting that great legacy.

The Indian Workers’ Association, under the leadership of Harpal, Jagmohan Joshi, Teja Sahota, Hardev Dhillon and Avtar Jouhl during the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, tirelessly and resolutely championed the cause of equality for workers of all national, racial and religious origins.

The IWA campaigned both against racist laws and against the socially debilitating racism experienced by the black population of Britain on the streets every day – taking direct action to combat the racist violence they encountered where necessary.

Struggling against capitalist imperialism, racism, colonialism and apartheid, and for the civil and employment rights of the Indian and British working class, Harpal and his comrades, and the growing group of communists and workers who were drawn to his leadership, tested their ideas and grew in strength and stature.

Harpal’s anticolonial and anti-apartheid work led him to work with the South African and Zimbabwean (Rhodesian) liberation fighters of the African National Congress (ANC), Pan African Congress (PAC), uMkhonto weSizwe (Spear of the Nation), Zanu and Zanla, and he met and spoke with great leaders including Chris Hani and Robert Mugabe, and later our South African communist comrade Khwezi Kadalie, whose grandfather had founded the first ‘native’ African union, and whose mother was a communist from the GDR (socialist east Germany).

Great miners’ strike of 1984-5

In 1984-5, Harpal led the IWA in a national programme of mass solidarity with the heroic miners’ strike. Indian communities across the country took food to the pickets and the miners’ halls, raised money for the striking miners and their families, and collected toys for their children at Christmas.

Harpal spoke at mass meetings of political solidarity with miners’ leaders including Arthur Scargill and Malcolm Pitt, and documented the course of that struggle in Lalkar. This concrete solidarity did much to break down the prevailing racism of British society at the time, used then as now to socially control the British working class.

The miners had long been considered the militant backbone of the British working class, living in isolated but vital and staunchly working-class pit villages across the country, particularly in South Wales, Yorkshire, Kent, Durham and the North East, and Scotland. The then Conservative prime minister Margaret Thatcher was determined to break the miners, in order to break the unions, casualise labour, close down ‘antiquated’ factories and heavy industry, ship building and car manufacture, to facilitate the export of capital and the exploitation of cheaper labour abroad. Her ideas coincided with those of Reaganism and Milton Friedman’s free-market fundamentalism, recently practised on the Chilean people.

The miners found themselves facing a well-armed and prepared state machine that was ruthless in the suppression of their resistance. Under Arthur Scargill’s leadership they came close, so close, to victory, but the strike was ultimately sabotaged by a ‘united imperialist front’ that extended from Labour and the Trades Union Congress (TUC) to the Tory government and the entire British state machine, with the fervent propaganda and financial backing of the capitalist press and the City of London financiers.

Despite their ultimate defeat, the genuine, heartfelt and spontaneous solidarity of the Indian working-class community, as well as Harpal’s leading role in promoting it, had a profound and lasting impact on the entire British working class.

Harpal, the IWA and our comrades together supported many landmark strikes of organised labour, from Fleet Street (Wapping) to Grunwick and the Hillingdon Hospital workers.

Antiracist struggle

Postwar Britain from the 1950s into the 2000s was a deeply racist society, based on the colonial ideology upon which the British empire had been built. The IWA struggled for workers’ equality, for the civil rights of immigrant and black workers, and against racism in all its forms.

As such, Harpal, Godfrey, Ella and Iris were also leading lights of the Campaign Against Racist Laws (Carl), and leading participants in the mass antiracist movement, campaigning and organising meetings and demonstrations across the country.

Collaboration of the National Front, Labour and the SPG in Blair Peach’s murder

In 1979, Labour prime minister James Callaghan sent police to protect the fascist and white-supremacist National Front (NF), which provocatively used the excuse of a general election (that brought Thatcher to power) to hold a racist rally among the Indian workers of Southall. Harpal and the IWA organised a mass antiracist march to protest, and kick the fascists out.

Thousands of police, including members of the notorious Special Patrol Group (SPG), were sent by the Labour government to beat the antiracist and Indian protestors off the streets. Scores were arrested that day, including Harpal.

A young New Zealand-born teacher, Blair Peach, was beaten to death by the SPG. It later transpired that the SPG thugs had doctored their truncheons illegally, boring them out and filling them with lead to make them lethal. The cracking of Blair Peach’s skull was therefore an act of premeditated murder. The SPG was wound up, only to be replaced by the similarly thuggish and brutal Territorial Support Group (TSG). And, predictably, no police assassin was held accountable for his crimes.

Stephen Lawrence

Nearly 15 years later, the IWA jointly organised a huge antifascist, anti-BNP march in Welling in 1993, after a string of racist murders had taken place in the area. These included that of Stephen Lawrence, a young black teenage boy, by a group of four fascist-minded youths with links to the fascist National Front and British National party. An enormous police presence was again put onto the streets to protect the fascists’ ‘book shop’ from which the local racists coordinated their activities.

In a predictable pattern, the Metropolitan police violently attacked the protestors, while the press made national propaganda that turned truth upside down, depicting the police as innocent victims of the aggression of the antiracist demonstrators. Harpal addressed the crowd that day, on behalf of the IWA, giving the marchers their slogan: “We are black, we are white; together we are dynamite!”

In 1962, IWA chairman Avtar Johal, a foundry worker and union leader who would become a close comrade of Harpal’s, invited Malcolm X to visit Birmingham, the scene of racial violence. Smethwick was a site of both east Indian and west Indian immigration after WW2. As with other immigrant communities, including Southall, migration was encouraged and initiated by local industry, which was in need of labour, and brought workers and after them their families from Britain’s former colonies.

The workers of Smethwick, as elsewhere in Britain, had long been subject to the racist imperial propaganda pushed by the British empire. Local Labour MP and later British Union of Fascists leader and MP Oswald Mosely had been replaced by the equally racist and repugnant Conservative MP Peter Griffiths, whose election slogan had infamously been: “If you want a nigger for a neighbour, vote Labour.” Griffiths supported a programme of social segregation in Britain, under which the Smethwick Conservative council bought up houses and offered them for rental to “whites only”.

“Racial prejudice was a constant blight,” said Comrade Avtar, and the IWA “devoted its energies to demonstrating that racism is a product of capitalism, and that the workers, no matter where they came from, shared common interests”. [5]

The IWA campaigned against casteism, communalism and separatism, for women’s equality and against dowry and arranged marriage, and it particularly took up the anticolonial and antiracist struggle of the South African masses struggling against the settler-colonial apartheid regime, as well as the equally vital cause of the liberation struggle of the Palestinian people, fighting to rid themselves of the yoke of the settler-colonial apartheid regime of Israeli zionism. Both regimes were, of course, backed to the hilt by their ‘motherland’ – British imperialism.

Fighting the corruption of the local Labour party in Southall led Harpal to contest local elections, in which he was narrowly defeated owing to the combined forces of Labour and its hangers-on.

Harpal and his comrades organised, and he spoke at, huge anti-apartheid and pro-Palestine rallies throughout the 1980s and 1990s. It was in this connection that Harpal made national speaking tours with Gora Ibrahim of the South African Pan African Congress (PAC) and met Chris Hani, South African communist and youth leader, shortly before his assassination. He also journeyed to meet the Palestinian Liberation Organisation’s (PLO) leader Yasser Arafat in Tunisia in 1986.

Among Harpal’s many writings were Zionism, a Racist, Reactionary and Antisemitic Tool of Imperialism and Imperialism in the Middle East (co-authored with Ella Rule), which summarise the historical origins of zionism as a British settler-colonial project to rule the middle-eastern colonies acquired by Britain by dint of World War 1 and the Sykes-Picot agreement (the secret treaties published by Lenin and the Bolsheviks after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia). The former book has since acquired a political life of its own. Both deserve to be read and studied today, in the aftermath of the Israeli genocide of 2023-25, which constitutes both a second Nakba, and a heroic continuation of the liberation struggle of the peoples of the middle east.

Irish liberation

Throughout the period of the armed struggle in the occupied six counties of northern Ireland, Harpal and the IWA organised regularly in solidarity with the national-liberation struggle of the Irish people, and hosted meetings with Gerry Adams and other Republican leaders at a time when it was illegal for them to speak, or for their voices to be heard on terrestrial television across Britain.

Marx famously wrote that “No nation that enslaves another can itself be free.” This has been especially true of the relationship between British and Irish workers, and Harpal and his comrades were firm supporters of a united Ireland consisting of all of its 32 counties.

Marx observed in 1870 that: “Every industrial and commercial centre in England now possesses a working class divided into two hostile camps, English proletarians and Irish proletarians. The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker as a competitor who lowers his standard of life. In relation to the Irish worker he regards himself as a member of the ruling nation and consequently he becomes a tool of the English aristocrats and capitalists against Ireland, thus strengthening their domination over himself.

“He cherishes religious, social and national prejudices against the Irish worker. His attitude towards him is much the same as that of the ‘poor whites’ to the negroes in the former slave states of the USA. The Irishman pays him back with interest in his own money. He sees in the English worker both the accomplice and the stupid tool of the English rulers in Ireland.

“This antagonism is artificially kept alive and intensified by the press, the pulpit, the comic papers, in short, by all the means at the disposal of the ruling classes. This antagonism is the secret of the impotence of the English working class, despite its organisation. It is the secret by which the capitalist class maintains its power. And the latter is quite aware of this.” [6]

With Elon Musk’s grotesque tweets about immigration, “Pakistani grooming gangs”, “white genocide”, etc, and with the entire government and parliamentary opposition (Labour, Tory, Liberal and Reform) and the entire capitalist press following his lead, we can see that these issues are far from finished with. As the capitalist crisis grows, racism and religious prejudice remain the principal ugly devices used by the British ruling class to stoke division and perpetuate their senile rule.

The oppression of Ireland by the British predated but mirrored India’s experience of the brutal and racist regime of the Raj, and their liberation struggles had long looked to and nurtured one other. The IWA, in fact, had claimed Shaheed Udham Singh as an early member, and he had become a staunch revolutionary with links to the Comintern, the Republican movement and the IRA (Irish Republican Army).

Irish leader Gerry Adams came to speak to meetings of Indian workers in Southall during the time of the Troubles. Under Harpal’s guidance, Indian and British workers discarded the chauvinist propaganda then omnipresent in the British press and in society and made common cause with their Irish brothers and sisters. This solidarity was a welcome breath of fresh air for our Irish comrades at a time when the words of Adams were routinely suppressed, and his voice was dubbed and censored in British radio and television news bulletins.

Before the advent of cable TV and the later ubiquitous Zee TV and Sunrise Radio, when there was no easy access to Indian language, news or culture in Britain, and when the first generations were struggling to build their lives here, the IWA was a genuine mass community and cultural organisation, which also politicised a generation of Indian workers to play a positive and progressive role in British working-class life.

Saklatvala Hall

As a national leader of the Indian Workers Association (GB) and a leading member of the working-class and Indian community, Harpal was a universally known leader and personality in Southall. It was for this reason that he and his comrades of the ACW built a community centre (now the CPGB-ML’s headquarters), Saklatvala Hall, in Southall.

Named after the great communist and MP for Battersea Shapurji Saklatvala, the hall was inaugurated with a meeting in December 1999 attended by Saklatvala’s daughter Sehri, and presided over by Harpal, with the other principal guest speaker being Arthur Scargill. [7]

The great test. 1990-91: the fall of the USSR, ‘An era of the blackest reaction’

The Russian Revolution of October 1917 was a beacon of hope for the workers of all countries. Lenin wrote that: “The workers of the whole world, no matter in what country they live, greet us, sympathise with us, applaud us for breaking the iron ring of imperialist ties, of sordid imperialist treaties, of imperialist chains – for breaking through to freedom, and making the heaviest sacrifices in doing so – for, as a socialist republic, although torn and plundered by the imperialists, keeping out of the imperialist war and raising the banner of peace, the banner of socialism for the whole world to see.” [8]

The USSR, and Comrade Stalin, in defeating the Nazi German imperialists and bringing communism from the realms of theory to the world of practical realities, had made the workers of the world a power. Harpal wrote extensively of the significance of the victories of the USSR and of the impetus it gave to the freedom and anticolonial struggles of the world’s peoples.

Harpal noted that Stalin had echoed Lenin’s sentiments and, in opposition to Trotsky, who continually campaigned against the building of socialism in the USSR, had defended it as being at the centre of the world revolution:

“What would happen if capital succeeded in smashing the Republic of Soviets? There would set in an era of the blackest reaction in all the capitalist and colonial countries, the working class and the oppressed peoples would be seized by the throat, the positions of international communism would be lost.” [9]

In the aftermath of the fall of the Soviet Union, when renegacy became the fashion, Stalin’s words were most tragically borne out. Guided by his deep study and understanding of Marxism-Leninism, Harpal stayed true to his principles: to the conviction that the working class is the ruling class in waiting, and that a socialist and communist society can be built in Britain and the world, for the greatest benefit, indeed the salvation of mankind.

“Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.” [10]

It was Harpal’s great misfortune to live at a time of great reverses for the communist movement. But it was to our great benefit that we had Harpal to take up the difficult cause of defending the liberation ideology of the working masses at such a dark time.

To navigate the rapids of revolution and the reverses of counter-revolution, to see the course of working-class liberation “despite the zigzags of history”, when so many others were shaken by these reverses, Harpal turned once more to a deep political and theoretical study and analysis.

“It is not difficult to be a revolutionary when revolution has already broken out and is in spate, when all people are joining the revolution just because they are carried away, because it is the vogue, and sometimes even from careerist motives. After its victory, the proletariat has to make most strenuous efforts, even the most painful, so as to ‘liberate’ itself from such pseudo-revolutionaries.

“It is far more difficult – and far more precious – to be a revolutionary when the conditions for direct, open, really mass and really revolutionary struggle do not yet exist, to be able to champion the interests of the revolution (by propaganda, agitation and organisation) in non-revolutionary bodies, and quite often in downright reactionary bodies, in a non-revolutionary situation, among the masses who are incapable of immediately appreciating the need for revolutionary methods of action.

“To be able to seek, find and correctly determine the specific path or the particular turn of events that will lead the masses to the real, decisive and final revolutionary struggle – such is the main objective of communism in western Europe and in America today.” [11]

Perestroika

It was in these circumstances that Harpal published his first book, Perestroika, the Complete Collapse of Revisionism. This profound analysis of an epoch-shaping event, which Harpal assumed that, like him, ‘everyone understood’, was written at the insistence of his comrades, as a series of Lalkar articles in 1990.

Having studied the evolving restoration of capitalism in the Soviet Union, the splits that resulted from this revisionism, the secret speech that Khrushchev made to the 20th party congress of the CPSU(B) in 1956, the economic debates within the USSR, and of course Stalin’s last great work Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR, Harpal understood the restoration of capitalism as it was happening. Many others did not, and were stunned at the apparent ‘defeat’ of communism, loudly proclaimed to be “the end of history” by the triumphant imperialist bourgeoisie and their ideologues – notably Francis Fukuyama.

Harpal explained to the IWA and the wider socialist movement, in this short but brilliant work, the economic and ideological causes of the dissolution of Soviet socialism – and therefore the lessons to be learned from this historical calamity. Many other movements and parties have failed to learn this historical lesson till this day. And many are, therefore, unable to move on with the work of building a revolutionary movement.

Harpal remained to the last a firm adherent of Marx and Engels, of Lenin and of Stalin.

Stalin Society

It was in these conditions that Harpal brought together the leading British antirevisionist communists such as Bill Bland, Kemal Majid, Ivor Kenna and Wilf Dixon, who wished to keep alive the communist movement and work towards the foundation of a genuinely revolutionary communist party in Britain, under the banner of the Stalin Society – which did not escape the attention nor the derision of the bourgeois press, but he nonetheless carried this vital mission forward.

The society was formed in 1991 to defend Stalin and his work on the basis of fact and to refute the capitalist, revisionist, opportunist and Trotskyist propaganda directed against him.

Stalin’s name is synonymous with communism, the October Revolution, and the overthrow of capitalist exploitation and imperialist tyranny. For this reason, the international bourgeoisie have spearheaded their attacks on working and oppressed peoples by slandering Stalin and the Soviet Union.

They have employed a variety of tactics to this end over the last century, but have been guided to a large extent by dissidents who betrayed the Soviet people, most notably Leon Trotsky. The powerful US-based Hearst press, sympathetic to Hitlerite Germany, was a pioneer in these methods, but the rest of the capitalist world’s media and political elites have not lagged behind.

The activity of the Stalin Society included: the study of and research upon Stalin’s writings and actions; the translation of material into and from other languages; the publication of material relating to such study and research; the celebration and commemoration of important occasions in Stalin’s life; the establishment of contact with other groups and individuals with a view to taking a common stand on issues and the joint organisation of future activities; and the establishment of contact with similar societies and groups abroad with a view to mutual benefit from experience and collaboration.

The brilliant output of the Stalin Society over a 30-year period did much to cement and preserve the revolutionary teachings of Marxism-Leninism and give a firm theoretical grounding to the core workers of both the Socialist Labour party after it was formed in 1996 and the CPGB-ML from 2004 onwards.

During this time, Harpal published his seminal works on Trotskyism or Leninism, on imperialism and on Labour party social democracy, and he brought together work on the women’s movement, the anti-imperialist struggles of the Indian, Palestinian and Zimbabwean peoples, and a criticism of imperialism’s many postcolonial, and post-Soviet wars.

Socialist Labour party, 1997-2004

As Tony Blair was coming to power, he led the Labour party in abolishing Clause IV of the party’s constitution, which had promised (falsely) to bring about “nationalisation of the means of production, distribution and exchange” in Britain. When the miners’ leader Arthur Scargill formed the Socialist Labour party (SLP) in 1996, as a response to this “betrayal”, Harpal greeted its foundation as a break between the working class of Britain and social democracy – the Labour party – which he saw as the chief social prop of the British capitalists amongst the working class. He understood that Clause IV was never intended to be implemented, and that the Labour party was always and everywhere a false friend to the British workers – ‘the enemy within’. It was his firm view that British workers could make no progress without combatting and destroying the Labour party’s hold over the socialist and trade union movement and wider working class.

In 1997, Scargill invited Harpal and his comrades to join his newly formed party and asked Harpal to stand as a candidate in the general election. The ACW (which had recently merged with the Association of Indian Communists to become the short-lived Association of Communists GB (ACGB), decided to throw in its lot with the SLP and dissolved itself, and Harpal went on to become one of the party’s key leaders, standing for election in Southall in 1997 and again in 2003.

Harpal dedicated himself to fighting to build the SLP into a militant working-class party with a Marxist understanding and political vision, and he used his position as education secretary to set up party schools and try to win over as many members as possible to his ideas. Notably, he persuaded the December 1997 congress to abandon the party’s ‘Black section’, championed by the SLP’s Trotskyite faction, as being divisive and insulting to black workers.

Harpal was among the first to recognise the poison of black nationalism and separatism within the working-class movement, and as a leader of the IWA had written and campaigned against it consistently. His numerous articles on the subject were collected into the book Bourgeois Nationalism or Proletarian Internationalism?, which was an early contribution to the struggle against the emerging, anti-Marxist ‘politics of identity’. Harpal always held that it was not the sole concern of the black workers to fight racism, since racism was an Achilles’ heel affecting the whole of the working-class movement – the secret by which the capitalist ruling class holds sway over a considerable section of the white working class. As such, it was the job of all workers to fight it. “I am not a black communist,” he said. “I am a communist, who also happens to be black.”

When it became clear that, despite the best efforts of Harpal and his supporters, the SLP could not move beyond Arthur’s vision of ‘old Labour’ and a ‘reformed’ capitalism, Harpal and his comrades were forced to leave that project – as the mass expulsion of the Yorkshire section of the party and half of the leadership NEC on spurious grounds made clear. Matters came to a head when the SLP congress in 2003 passed a resolution, opposed by Arthur Scargill, defending the right of socialist north Korea to have a nuclear deterrent, the arguments in favour of the motion having been put by Harpal and his comrades who had been working in support of the DPRK for very many years. Very shortly afterwards, Arthur organised the expulsions.

But the time spent with comrades of the SLP had not been in vain. This was the organisational impetus necessary for the founding of Britain’s first truly revolutionary party since 1951, the Communist Party of Great Britain (Marxist-Leninist).

Antiwar and anti-imperialist campaigning: ‘Stop the War’

While inside the SLP, Harpal and his comrades played a leading role in opposing the new wave of post-Soviet colonial wars, starting with Nato’s brutal bombardment and dismemberment of Yugoslavia in 1999, and the illegal imprisonment, trial and custodial torture and extra-judicial murder of its leader, Slobodan Milosovic. Comrades took part in the colossal two-million man march against the second Iraq war in February 2003, and were an integral part of the Stop the War Coalition (StW).

After the formation of the CPGB-ML, the new party affiliated to Stop the War. Of course, it was never invited to join StW’s leadership body or to send a speaker to any of its platforms, such was the hostile sectarianism of the revisionists and Trotskyites who ‘led’ the antiwar movement into the lap of the Labour party – the very party that in or out of office never lagged behind the Conservatives in promoting, supporting and financing the wars.

Despite this, the party persuaded the delegates at StW’s national conference in 2009 to adopt its resolution on non-cooperation with imperialist war crimes, but was unable to get StW to act upon this resolution, which is leaders quietly pigeonholed. The coalition, badly misled by such left-Labour luminaries as Tony Benn, Jeremy Corbyn et al, tolerated the CPGB-ML’s presence in their ranks until they found an excuse to expel it, in 2011, over the issue of Libya.

As that war was in preparation, and the bourgeois media were ramping up their hysterical propaganda against Libya’s revolutionary leader Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, the StW leadership of John Rees, Lindsay German, Chris Nineham, Andrew Murray et al went so far as to organise a demonstration outside the Libyan embassy in London, denouncing Colonel Gaddafi as a dictator. They were joined by the wahhabist foot-soldiers of imperialism in a disgusting display of pro-Nato, pro-imperialist servility to the ruling class. The CPGB-ML denounced this pro-war activity and line of the ‘Stop the War’ Trotskyites and revisionists – and was promptly and unconstitutionally expelled for ‘criticising its leadership’.

When the party tried to appeal to the next annual conference against this disgusting act, its comrades were refused permission to speak, shouted down and ejected by none other than that ‘great white hope’ of the fake-left, Jeremy Corbyn. The party, of course, continued its antiwar work outside that bankrupt organisation.

It is an enduring credit both to Harpal’s proletarian internationalism, his anti-imperialism and his personal courage that he journeyed both to Iraq ahead of the Labour onslaught in 2003, and to Libya in 2011. Together with Ella Rule and his Somali and Belgian comrade Mohamed Hassan, then in the PTB (Workers Party of Belgium), he went to Tripoli to deliver a message of solidarity to the Libyan people – even as the destruction of that proud independent and developed north African country was under way by the neo-Nazi Nato Luftwaffe’s cowardly aerial bombardment.

These actions earned him the derision of the left-imperialists in our Stop the War and Trotskyite movement, eager as ever to prove themselves useful tools to the Labour party and the British ruling class. But his proud and courageous solidarity has stood the test of time, and we are grateful for his leadership and loyalty to the cause of the oppressed.

Without adopting this approach, the British workers will never see socialism.

China

Harpal and his comrades responded to the many attacks on communist China with solidarity and support. In particular, they founded the ‘Hands off China’ campaign when the attacks crescendoed in the lead-up to the Beijing Olympics in 2008.

When the CPGB-ML’s seventh party congress charged Harpal to write a book on China, explaining Socialism with Chinese Characteristics, Harpal once more took up a serious study of China’s economic and political conditions and wrote a definitive analysis that remains obligatory reading for communists.

Revolutionary seizure of the land in Zimbabwe, 2000

In 2000, Labour ‘minister of state development’ (in effect the colonial secretary of British imperialism) Clare Short finally and officially reneged on Britain’s commitment to finance the buy-back of Zimbabwe’s colonial lands, seized by their colonists from the indigenous black population. A second wave of struggle arose in Zimbabwe, with the veterans of the armed struggle moving to seize lands without compensation and, after some hesitation, this was formally legalised by Robert Mugabe’s Zanu-PF government.

The howls of US and British imperialism were loud, and the sanctions pressure from global capital and the propaganda war from global media (the BBC foremost among them) were intense. The threat to their property rights and ongoing exploitation of the African masses and natural resources were clear.

In 2004, while a leader of the SLP, Harpal brought his work on Zimbabwe together into his book Zimbabwe Chimurenga! – from the Shona slogan Pamberi na chimurenga!, meaning ‘Victory to the liberation struggle!’ It was a tribute to the heroic and victorious struggle of the Zimbabwean masses under the leadership of Zanu-PF, and also a powerful polemic in justification of the confiscation of the land without compensation and its division among the peasantry.

In 2005, Harpal was invited to attend and speak at the Zanu-PF congress to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Zimbabwe’s liberation, and he gladly returned to the warm embrace of the Zimbabwean comrades who, when they struggled together in the 1970s, would weave Harpal and his comrades’ names into their Shona liberation songs.

Harpal spoke to the full plenary session, shortly after meeting and greeting Robert Mugabe after a 25-year hiatus that had seen them step on such very different paths – one as a national leader, the other as an ongoing revolutionary foot soldier in the belly of the imperialist beast.

Harpal’s contribution electrified the audience. In a speech that was televised nationally, Harpal recalled that the people of Zimbabwe had won their independence with guns in hand, after a fierce and protracted struggle in which they had made great sacrifices and that they had not done so to remain servants in their own land!

They had done so to gain control of the natural mineral resources and the land of their country. Britain had not kept its side of the bargain and the only way to settle the historical injustices of colonial robbery and bloodshed, and of apartheid racism, in the absence of these promised reparations of £1bn from Britain, was the revolutionary seizure of the land. Be it noted in passing that it is typical that a ‘Labour’ government would be at the heart of a policy more dishonourable and reactionary than the Tory government of Maragret Thatcher.

The seizure of Zimbabwe’s land from the white farmers, without compensation and its division among the peasantry was, moreover, the greatest revolutionary democratic act since the seizure of the feudal estates of France by the great French Revolution of 1789.

Britain and the USA were not only worried about Zimbabwe – they were then, as they are now, anxious to preserve the iniquitous monopolisation of the land throughout Africa and their former colonial, now neo-colonial, possessions. In particular, they worried about the example set by the Zimbabwean masses and Zanu-PF to the South African masses and the ANC. They were also outraged by the arrest of Mark Thatcher for his colonial escapades in Equatorial Guinea and for flouting the laws of Zimbabwe. They were further angered by the revolutionary assistance offered to the Democratic Republic of Congo’s independent government of Laurent Kabila. With these steps, Africa had moved away from the era of colonial domination and humiliation, and had taken a giant step in the direction of true and lasting economic and political liberation and dignity. Pamberi Na chimurenga! A luta continua!

Once he started speaking, Harpal pleaded with the assembled delegates that he should not be interrupted by the loud and stormy applause he was receiving, as he only had 15 minutes to speak – whereupon Comrade Mugabe stood and insisted that “There is no time limit for Comrade Brar!” When Harpal had finished speaking, amid thunderous applause, Mugabe held aloft the copy of the book Zimbabwe Chimurenga! that Harpal had gifted him, and which he had been thumbing, and said: “I know Comrade Brar. We worked together during the liberation struggle but lost contact; it is good to be back in touch! We have not written the history of our own liberation struggle, but this book contains that history. You must all get a copy and read it!”

The Communist Party of Great Britain (Marxist-Leninist)

It had always been Harpal and his comrades’ wish to re-found the communist movement of Britain on a solid Marxist and Leninist basis, for without organisation and revolutionary leadership, as their entire life struggle and work had shown, the working-class has nothing.

“In its struggle for power the proletariat has no other weapon but organisation. Disunited by the rule of anarchic competition in the bourgeois world, ground down by forced labour for capital, constantly thrust back to the ‘lower depths’ of utter destitution, savagery, and degeneration, the proletariat can, and inevitably will, become an invincible force only through its ideological unification on the principles of Marxism being reinforced by the material unity of organisation, which welds millions of toilers into an army of the working class.” (VI Lenin, One Step Forward, Two Steps Back, 1904)

The details and reasons for formation were well documented at the time of the party’s first congress, held on Saturday 3 July 2004 in Saklatvala Hall, Southall. [12]

The party’s programme and rules were written by Harpal and adopted unanimously, enshrining the key lessons both of the struggle to build the SLP and of the great teaching of Leninism, as adapted to suit the conditions of Britain.

In the 20 years of its history, Harpal was the guiding force of the CPGB-ML, guiding and teaching the membership, initially as founding party chairman (until its eighth congress when he stepped down because of his advanced years). However, he remained a highly active member of the central committee for the rest of his life and died a proud Communist party member.

Harpal was undoubtedly a great disciple of Marx and Lenin, recognising that the Great October Socialist Revolution in Russia was a watershed of cultural enlightenment and freedom for humanity. Harpal’s critique of Trotskyism, his defence of the revolutionary teaching and leadership of Josef Stalin, and his critique of Khrushchevism and the revisionism that caused the downfall of Soviet socialism are among the lasting theoretical contributions he bequeathed to the communist movement.

The long, tumultuous and at times arduous struggle of the CPGB-ML aims to carve out a place in the political life of Britain, to reclaim a revolutionary tradition and trajectory for the British working class, to reclaim the birthright of the proletariat as the ruling class in waiting and end the shameful period of its abject servitude and forced wage-slavery for capital.

Fully supported by Lalkar and by Comrade Harpal, the party has had to deal with all the questions that dog the British and world proletariat, all the subtle and crass means by which the proletariat is held in subjection as a class. Its congress resolutions and the output of its paper Proletarian, its website, meetings, video-communications and publishing house, its leaflets, pamphlets and books have reflected this journey – and Harpal’s immortal contribution is reflected across all of these great and enduring gifts to the proletariat, and to mankind.

Lalkar and the CPGB-ML have dealt with the correct approaches to immigration and racism; Scottish nationalism and independence; identity politics and black separatism vs proletarian internationalism and working-class solidarity. They have dealt with the issues of bourgeois feminism vs women’s liberation as a part of the struggle for socialism. They have considered the impact of the latest transgender trend and the divisive influence of identity politics.

They have tirelessly campaigned to expose the Labour party and reduce its hold on the British working class. They have analysed and exposed British imperialism and the effect that this has on the British working-class movement. They have campaigned ceaselessly for the support and victory of the Palestinian liberation struggle, and the ejection of Anglo-American and EU imperialism from the whole of the middle east.

They have campaigned for the defeat of Britain’s imperialist Tory and Labour governments and parties and exposed their dirty colonial wars in Iraq, Yugoslavia, Sierra Leone, Afghanistan, Libya, Syria, Lebanon etc. They have brought solidarity to the peoples of the socialist world, forging close links with the Cuban people and the Communist Party of Cuba, and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and its leadership in the Workers’ Party of Korea.

Internationalism

While Harpal was born in India, he was a true Briton and a great leader of the British working class. Throughout all of his work and struggle among the British workers, he never forgot that proletarian internationalism was the only weapon that can secure lasting victory over capital, and he took a keen interest in fostering links with the the communist movement in all countries.

For many years, the Belgian Workers party (PTB) under the leadership of Ludo Martens was a close fraternal organisation. It was Harpal who encouraged Ludo to give up the self-applied label of ‘Maoist’, and rather consider himself a Marxist-Leninist.

Reading Ludo’s books on Another View of Stalin and The Velvet Counter-Revolution, Harpal appreciated his comrade’s intellect and contribution, while being able to give gentle criticism of the points where Ludo had made undue concessions to the narrative of the imperialists, particularly in regard to the trope that Stalin made ‘mistakes’ – mistakes that are never specified, ensuring there is no possibility of ascertaining whether it is Stalin or his ‘critics’ who are mistaken. Ludo accepted the criticism.

Ludo had enormous respect for Harpal, and they had a close friendship until his dying day. Ludo felt keenly his responsibility toward the liberation struggle in the Congo, and the PTB suffered badly when he relocated to Kinshasa. When he returned, he suffered a stroke, and Harpal, Ella and Ranjeet visited him in Belgium, just before his death. Despite his ill-health, he was able to express regret for the turn his party had taken towards social democracy and away from Marxism-Leninism.

For a time, the PTB’s annual 1 May event, and the international seminar the PTB organised in Brussels at the same time, was a focus of the revolutionary communist movement, struggling to come to terms with the fall of the USSR and the collapse of the eastern European people’s democracies. From this forum, Harpal made contacts with revolutionary communist groups and parties from across Europe, the Americas and further afield, including the re-formed communist parties within the USSR.

He frequently gave presentations regarding the USSR, imperialism and many aspects of current revolutionary work and struggle. Many of Harpal’s papers, speeches, articles, books and pamphlets have been translated by these comrades and parties into diverse languages, including French, Flemish, German, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese, as well as Korean, Hindi, Punjabi, Urdu, Arabic, Russian, Hungarian, Czech and more. Indeed, while writing this obituary, we have heard news that our comrades in Union Proletaria (Spain) are finishing their work of translating and producing Harpal’s now famous pamphlet on Zionism, a Racist, Reactionary and Antisemitic Tool of Imperialism.

The recent founding of the World Anti-imperialist Platform declares its ideological debt to Harpal’s work and teaching. His daughter, Joti, has been central to much of its work, together with many international comrades.

Harpal went to lay flowers on Stalin’s grave on the anniversary of the Great October Revolution and spoke in Red Square, at the wall of the Kremlin, to a great demonstration on 7 November 1997. He noted that many Red Army men listened attentively to the translation of his speech, which concluded with the words, that in the great land of Lenin: “Socialism will come, if not in my lifetime, then in yours. The USSR will undoubtedly be born again and in the words of the great Russian playwright Chernachevsky, ‘There will be joy and laughter in our streets.’”

Harpal has preserved and applied the great teachings and liberation ideology of Marxism to the communist movement and the modern conditions of Britain. He has lived a remarkable and productive life. His legacy lives on in his work, his books and articles, his extensive collection of recorded speeches and presentations, and by the new generations of British communist workers who are swelling the ranks of the CPGB-ML and the progressive movement.

If Harpal could say one thing to us it would be to: “Guard the party as you guard the apple of your eye.” He struggled to found and build it in the most difficult conjunction of circumstances, after the fall of the once mighty USSR. It is his life’s work, and he gave to it his whole being. It is a great gift that he leaves us: the best of Britain. His work is relevant to communists worldwide for shedding light on the situations of India, of the Soviet Union and China, and of the working-class revolutionary culture of all nations. Harpal was a true proletarian internationalist.

Harpal thought creatively about how to solve the problem of uniting revolutionary politics with the mass of the British workers. To that end he worked with, met, discussed and collaborated with the greatest revolutionaries and British working-class leaders of his time, among them Manchanda, Ludo Martins, Robert Mugabe, our Cuban, Korean and Chinese comrades, Avtar Johal, Jagmohan Joshi, Arthur Scargill, Frank Cave and Bob Crow.

But the greatest and most self-sacrificing comrades, and his true friends and comrades, were always those unsung heroes: Maysel (known as Kathy Sharp in political circles), Godfrey Cremer, Iris Sloley, Ella Rule, Deborah Lavin, Isabel Crook, Jack Shapiro and many others.

With Lenin, Harpal realised that “without a revolutionary theory, there can be no revolutionary movement”. That was the slogan he inscribed on the banner of Lalkar. And it was Lenin’s insightful way of paraphrasing Marx: “There is no royal road to science, and only those who do not dread the fatiguing climb of its steep paths have a chance of gaining its luminous summits.”

For Harpal, study was a practical part of politics. Without it, no party can ever succeed in effectively leading the working people to bring an end to their current state of servitude – their wage-slavery. This was an early realisation of Harpal’s, and his work – together with that of the CPGB-ML of which he was the greatest founding member – is the enduring legacy that he leaves us.

A luta continua!

Notes

[1] K Marx and F Engels, The Communist Manifesto, 1848.

[2] Report by VI Lenin to the fifth congress of the RSDLP on the St Petersburg split and the institution of the party tribunal ensuing therefrom, 1907.

[3] The second congress of the Communist International, reports and speeches by VI Lenin, 1920.

[4] VI Lenin, What Is To Be Done?, 1901.

[5] When Malcolm X visited Smethwick after racist election by Aina Khan, Al Jazeera, 21 February 2018.

[6] Letter by K Marx to Sigfrid Meyer and August Vogt in New York, 9 April 1870.

[7] Saklatvala Hall opened, Lalkar, January 2000.

[8] Letter to American Workers by VI Lenin, August 1918.

[9] Report by JV Stalin to the seventh enlarged plenum of the ECCI, December 1926.

[10] K Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, 1852.

[11] VI Lenin, ‘Left-Wing’ Communism, an Infantile Disorder, 1920.

[12] Formation of the CPGB-ML, Proletarian, August 2004.