Reproduced from the Class Consciousness Project, with thanks.

*****

I was inspired to write this after re-reading an excellent article on cultural capitalism posted on the Class Consciousness Project website on 1 August. It set me thinking about the cultural dimension of ruling-class manipulation, an aspect I had not previously given much attention to, particularly in relation to food, and to possible solutions.

There is an urgent need for nutritious, affordable, socialised food provision for the sustenance of the people, as a direct alternative to the unhealthy junk food relentlessly pushed at us via wall-to-wall corporate advertising.

A policy that would be implemented as surely as night follows day in a planned socialist economy is the provision of a national public food service network – what would be in effect a culinary equivalent of the NHS. This would guarantee every person access to healthy meals, provided on the basis of human need rather than private profit. It could be called something along the lines of The Peoples Table – a social institution that would ensure that no one is left to the predations of fast-food corporations.

Such a system could, in principle, be established under a capitalist government, if that government placed the welfare of its people above the demands of capital. However, in practice, our governments act as instruments of imperialism, concerned only with safeguarding profits for the corporations they serve.

The ruling class would be opposed to such a measure, but it would not cross any of the red lines that would bring tanks out on to the streets. It’s not on the same level as taking the financial corporations of the City of London into public ownership without compensation, exiting Nato, or expelling the US military from British soil.

Benefits of a national canteen programme

Of course, none of the contemptible roster of British imperialist parties would ever implement such a worthy scheme, but it is, I think, worthwhile, if only as an intellectual exercise, to give a brief sketch of how the stolovayas worked in practice in the Soviet Union, and how it might look if something similar were introduced to Britain. Along with the immense benefits it would bring to workers across the country.

There is, in fact, one corner of Britain where the principle of cheap publicly funded, heavily subsidised meals is upheld: the Houses of Parliament. There used to be many other workplaces that offered subsidised meals but most of these are gone now, so cut-price meals are reserved for MPs, peers and parliamentary staff.

At a time when many working-class families rely on food banks in the midst of a cost-of-living crisis, highly-paid MPs are getting food welfare. Since 1 April 2025, the basic annual salary for a backbench MP has been £93,904 – roughly three times the median British wage of around £31,000. This is no accident; it stands as a sharp illustration of how Britain’s political order is built upon and sustained by class privilege.

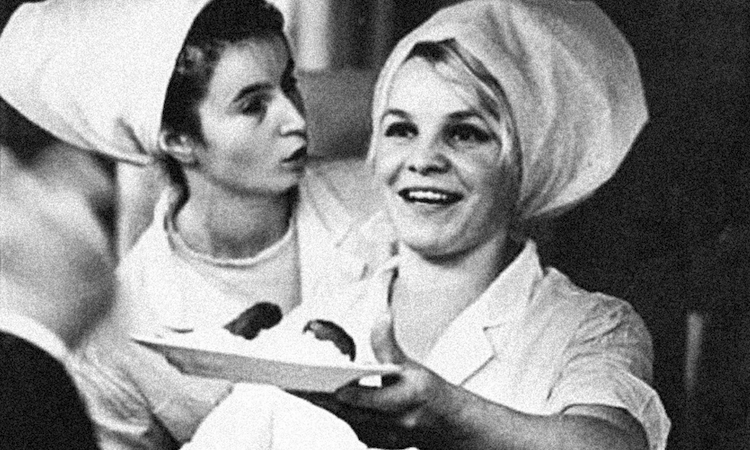

The outstanding historical example of low-cost social food provision for all was the network of Stolovayas in the Soviet Union. Stolovayas (meaning ‘dining rooms’ in Russian) were the Soviet canteens where workers could get hot, filling meals for just a few kopeks. They were an example of socialist public provisioning based on the principle that affordable nutritious food is a social right.

While some public canteens had existed in Russia before 1917, they were expanded rapidly after the October Revolution as part of the effort to socialise domestic labour and to guarantee affordable nutrition for all.

From the 1930s, stolovayas were widespread across factories, offices, schools, universities, railway stations, and in communities across the Soviet Union, serving millions daily at heavily subsidised prices. They acted as a social equaliser, with managers and workers eating the same food in the same halls, and were a key tool for improving health, and supporting industrial productivity.

According to the website Russia Beyond: “The idea of organised collective dining out fitted very well with the ideology of the young Soviet state: a kitchen of one’s own was considered a relic of the past, a woman should be freed from ‘kitchen slavery’ and given freedom and work, on a par with a man. Kitchens were turned into workshops and outsourced. Thus, the socialist revolution was followed by a lifestyle revolution.” (What was it like eating out during the Soviet Union?, 11 December 2018)

By the 1970s, there were hundreds of thousands across the Soviet Union, including special canteens for students, soldiers and railway workers. But by the late 1980s, the economic crisis brought on by revisionist sabotage and cuts to subsidies undermined the system, leading to poorer food and long queues. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, most stolovayas either closed or became capitalist-run restaurants.

British Restaurants in WW2

During the second world war, Britain established communal dining halls known as British Restaurants, run by local authorities with government support, to provide cheap, nutritious meals when food rationing was tight and there was widespread disruption to domestic cooking.

These dinning rooms offered simple but healthy food at fixed, low prices, without the need for ration coupons, which meant that anyone – workers, families, or those bombed out of their homes – could eat there. At their height more than 2,000 British Restaurants were functioning across the country, playing a central role in maintaining food security and public morale.

This experience demonstrates that, when backed by political will, a system of universal, affordable and nutritious public dining can be organised, even in the oldest part of the imperial core.

Despite historical precedent, it may seem a tad utopian to explore the social and class impact, and the benefits to workers, of a national public food service network; after all, such a policy appears highly unlikely to be introduced in a moribund imperialist country like Britain.

To initiate this in Britain would entail the setting up of a comprehensive network of The People’s Table that would guarantee that healthy, affordable meals were available to all, provided as a social good. If we set an illustrative value of £5 as the price of a full family meal, the result would be cheaper, healthier food than frozen sections of supermarkets or junk-food chains can offer, and a shift of food provision from creating corporate profit to meeting the health and nutritional needs of the people.

So how might it look in practice? It would be a state-owned and funded national network, with all communities across the country having access to a People’s Table. In rural and more isolated areas, this could be delivered by mobile units. Wherever possible, food used would be locally sourced, with menus built around seasonally available fruit and vegetables.

This programme would create many tens of thousands of proper jobs – secure, permanent positions with pensions, sick pay and dignity. From cooking and serving to procurement, transport and administration, every role would be paid at a proper living wage, with unions recognised and membership actively encouraged.

This stands in total opposition to the McDonald’s et al model: corporations built on low pay and zero-hour contracts. The thousands of secure, socially useful jobs created would vastly outnumber the insecure junk-food jobs that would disappear. And the results would be immediate: instead of families queuing at food banks, they would sit down to decent meals at affordable prices.

The benefits would be immediate in terms of health and nutrition, social cohesion and even educational outcomes. Working-class families would be able to afford to eat a healthier diet at a fraction of take-away and supermarket costs, alleviating pressure on household budgets, and allowing some circulating of money back into local economies.

The consequent decline in the prevalence of obesity, Type2 diabetes, malnutrition and other preventable diet-related illnesses would reduce long-term pressures on the NHS and social disfunction. A national public food network would embody the principle that food is an essential component of social reproduction, not merely a commodity.

What I have tried to show is that socialism offers the workers of Britain a practical vision: a state capable of guaranteeing cheap, healthy food as a right, delivered socially through rational planning and economies of scale.

Thinking about this issue constantly for a few days has reminded me of the line that the presenter used to close most episodes of the old TV game show Bullseye: “Come and have a look at what you would have won.”

If Britain were socialist, this prize would already be ours.