The following article is reproduced from the Marx Engels Institute with thanks.

*****

“There is a legend, in our country as well as in China, on the miraculous ‘Book of the Wise’. When facing great difficulties, one opens it and finds a way out. Leninism is not only a miraculous ‘book of the wise’, a compass for us Vietnamese revolutionaries and people: it is also the radiant sun illuminating our path to final victory, to socialism and communism.” (The path which led me to Leninism by Ho Chi Minh, April 1960)

It is now 99 years since the, tragically early, death of Vladimir Ilych Ulyanov known to the world forever now simply by one name – Lenin.

By the time of his death at the age of 54 he had, as the leader of the Bolshevik party, revolutionised Marxism and founded the world’s first workers’ state. For this he remains reviled by the capitalist class and the intellectual eunuchs it employs on the left and the right of bourgeois politics to churn out slanders against communism and its leaders.

What is the significance of Lenin, his life, work and legacy today? Firstly, one must state that all of these things have been traduced and misrepresented not only by our class enemies in the form of the bourgeois leaders and their paid hacks but also by those who have called themselves communists and socialists.

Take, for example, the question of democratic centralism. All of Lenin’s work rests upon this key theoretical and organisational breakthrough: his understanding of the dynamics of party organisation and the truly dialectical relationship between the two concepts, democracy and centralism.

In the 1901 work What Is To Be Done?, Lenin outlined his thinking on party organisation as part of a debate within Russian Marxism. This debate was generated by the wider problem in the Second International regarding the ideas of Eduard Bernstein and his open advocacy of reformism (known as economism).

In retrospect, Bernstein was merely the first to come out and say openly what most of the German SPD leadership had already arrived at in private. Bernstein endorsed a reformist approach, believing that with the advance of the SPD, its becoming a mass party with deep roots within the German working class, the road to socialism lay within through the bourgeois-democratic institutions of the German imperial state.

The SPD had gone, in the space of ten years at the end of the 19th century, from enduring heavy legal restrictions under the Bismarckian antisocialist laws to gaining 20 percent of the vote in Reichstag elections, and with an ever increasing trade union presence.

With the antisocialist laws gone and the German ruling class grudgingly accepting the role of the SPD within the bourgeois political system, Bernstein and his followers across Europe argued that this was the way forward: that the opposition of the ruling class would be overcome, and that the winning of the vote by the working class would ensure a peaceful transition to socialism.

Lenin, Rosa Luxemburg and others followed in the wake of Karl Kautsky in arguing against this, Kautsky at the time still being regarded as the leading theoretician of revolutionary Marxism in the Second International.

Lenin’s contribution, though, was to be far more important than any others, because it was within his work What Is To Be Done? that he set out his foundational insights. In arguing against the Russian advocates of Bernsteinian reformism, Lenin took up the debate regarding consciousness within the working class.

Some Russian Marxists organised around the newspaper Rabochaya Mysl argued that the Marxists must follow the consciousness of the working class, which would naturally evolve towards a struggle for ever greater reforms. Lenin quoted from their newspaper as follows:

“The workers fight knowing that they are fighting not for the sake of some future generation but for themselves and their children.” (Leader article in Rabochaya Mysl No 1, cited in VI Lenin, What Is To Be Done?, 1901, Chapter 2)

Lenin responded as follows:

“Phrases like these have always been a favourite weapon of the west-European bourgeois, who, in their hatred for socialism, strove to transplant English trade unionism to their native soil and to preach to the workers that by engaging in the purely trade union struggle they would be fighting for themselves and for their children, and not for some future generations with some future socialism. And now the ‘VVs of Russian social democracy’ have set about repeating these bourgeois phrases.”

Anyone who has been involved with trade union activity will have heard these arguments rehashed again and again. I have heard them and had them thrown at me many times. Lenin’s reference to ‘English trade unionism’ is quite, deliberate because trade unionism in England was the first to develop a leadership and national structures that were incorporated into the structures of the British state from the very point when the Trades Union Congress was founded.

English trade unionism, and the German example of the SPD’s growth and success as a mass party, became the inspiration for the Bernstein era of reformism. This was repeated again 50 years later, when the European communist parties made many of the same errors and ended up carrying out similar levels of betrayal to their Second international predecessors.

Lenin opposed the idea, expressed by Bernstein and his adherents, that politics always followed economics. This crudely reductionist viewpoint has been presented by the enemies of communism as being the point of view of Karl Marx and of Lenin, but the reality is that both men could not have been more clear in their opposition to such a point of view.

Marx warned of the dangers of this economistic approach in his 1875 work Critique of the Gotha Programme, and Lenin in 1901 argued as follows:

“Since there can be no talk of an independent ideology formulated by the working masses themselves in the process of their movement, the only choice is – either bourgeois or socialist ideology. There is no middle course (for mankind has not created a ‘third’ ideology, and, moreover, in a society torn by class antagonisms there can never be a non-class or an above-class ideology). Hence to belittle the socialist ideology in any way, to turn aside from it in the slightest degree means to strengthen bourgeois ideology.” (Chapter 2)

What Lenin was drawing upon here is the fact that capitalist society needs to be seen as a whole, and its ideology is everywhere and reflected even inside workers’ movements. The argument by the likes of Rabochaya Mysl (following Bernstein) was that the working class would spontaneously develop a socialist consciousness via trade union-like struggles, and that therefore the role of Marxists was simply to immerse themselves within the struggles of workers and not speak of the insoluble nature of class contradictions under capitalism or the need for revolution.

Lenin argued that even the most radical expressions of trade union struggle will fall back into bourgeois ideology without the active intervention of a revolutionary party that can bring to workers the core ideas of Marxism: that class contradictions cannot be resolved; that capital has no choice but to continually attack labour; and that the only way to resolve these contradictions is for the working class to overthrow and dispossess the capitalists.

The history of trade unionism across the advanced capitalist world over the 99 years since Lenin’s death has shown him to be correct on this point over and over again.

Even at its most radical point, in the early 1970s, the trade union struggle within Britain imploded precisely because the shop floor militancy went up to the point of making the writ of the management in some industries (such as car making) very fragile, but could go no further.

After years of intense struggle, the trade union leaders were able to divide, defeat and demoralise the working class because the capitalist class refused to simply back down and go away. They have to keep pushing against the working class to defend their class interests. No matter how many concessions the working class attains, the capitalist class is always looking for ways to seize these back and ways to divide the proletariat.

Without a revolutionary party worthy of the name in the early 1970s, this high tide of industrial struggle rapidly receded again.

The strength of bourgeois ideology within the working class and trade unionism should not be a surprise. As Antonio Gramsci was later to demonstrate, one of the great strengths of capitalism is the fact that it has at its disposal a huge variety of ways to create and recreate its ideology.

Bourgeois ideology isn’t just a matter of state propaganda or the hysterical headlines in reactionary newspapers: it comes from every single piece of media and culture all around us. It enters our consciousness almost as soon as we draw our first breath. Precisely because it is so pervasive, it is necessary to build a revolutionary party in order to have an organisation where bourgeois ideology and its role can be clearly understood and counteracted.

Trade unionism does not provide that kind of organisation precisely because it is locked into a day-to-day struggle with the employers. Because it is rooted in contesting the question of how capitalist relations of production are to be imposed upon the working class, it cannot truly raise the question of ‘if’ such relations should exist at all.

Lenin went on to discuss what kind of agitation communists (he used the term ‘social democrats’ because this was the common term used to describe at the time what is now called communism) should carry out amongst the working class:

“The question arises, what should political education consist in? Can it be confined to the propaganda of working-class hostility to the autocracy? Of course not. It is not enough to explain to the workers that they are politically oppressed (any more than it is to explain to them that their interests are antagonistic to the interests of the employers).

“Agitation must be conducted with regard to every concrete example of this oppression (as we have begun to carry on agitation around concrete examples of economic oppression). Inasmuch as this oppression affects the most diverse classes of society, inasmuch as it manifests itself in the most varied spheres of life and activity – vocational, civic, personal, family, religious, scientific, etc, etc – is it not evident that we shall not be fulfilling our task of developing the political consciousness of the workers if we do not undertake the organisation of the political exposure of the autocracy in all its aspects?” (Chapter 3)

What was Lenin arguing for here? He was making the case that the political education carried out by communist parties must be oriented around aiding workers to view capitalism (and their place as the true creators of wealth within it) as a system, rather than as a series of disconnected elements.

The bourgeoisie in its propaganda specifically tries to encourage fractured and fragmented thinking within the working class, to prevent them from making the connections between their everyday struggles and the wider question of which class holds power in society. Therefore, communists must strive to counteract this.

What, then, must be the objective of such a party in terms of political education? Lenin stated very clearly what kind of consciousness the party must aim to develop among workers:

“In order to become a social democrat, the worker must have a clear picture in his mind of the economic nature and the social and political features of the landlord and the priest, the high state official and the peasant, the student and the vagabond; he must know their strong and weak points; he must grasp the meaning of all the catchwords and sophisms by which each class and each stratum camouflages its selfish strivings and its real ‘inner workings’; he must understand what interests are reflected by certain institutions and certain laws and how they are reflected.

“But this ‘clear picture’ cannot be obtained from any book. It can be obtained only from living examples and from exposures that follow close upon what is going on about us at a given moment; upon what is being discussed, in whispers perhaps, by each one in his own way; upon what finds expression in such and such events, in such and such statistics, in such and such court sentences, etc, etc.

“These comprehensive political exposures are an essential and fundamental condition for training the masses in revolutionary activity.” (Chapter 3)

What Lenin was stating here is that the party must aim to develop the consciousness of the working class to the point where working-class communists can not only understand the role of individuals and institutions, but how these sit within the system of capitalist social and economic relations. The job of the party is thus to recruit, educate and organise workers, arming them with this knowledge of how capitalism truly functions.

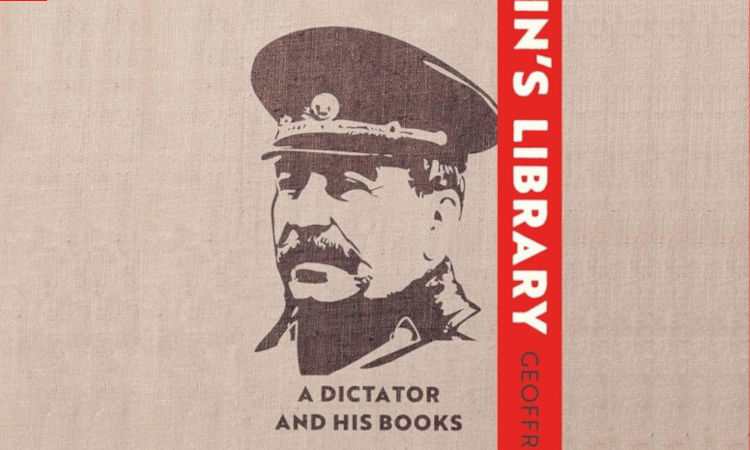

In his work The Foundations of Leninism, Josef Stalin was to further spell out the relationship between the party and the class:

“But the party cannot be only an advanced detachment. It must be at the same time be a detachment of the class, part of the class, closely bound up with it by all the fibres of its being.” (1924, Chapter 8)

The worker armed with this most vital understanding of how capitalism operates as a system must then take that knowledge to their workplace, trade union and community in order to win over others to this position. Gramsci, who has been far too easily claimed by opportunists, showed an acute understanding of this in his essay, written whilst imprisoned by the Italian fascist regime, entitled The Intellectuals.

Lenin developed the idea of the worker-communist as being the root of the party, of developing and maintaining the relationship with the masses, taking the experience of the workers into the party in order to guide and develop the party line and then, when that has been debated and decided upon, taking the line of the party back to the working class and seeking to apply it in practice.

Thus the party is not merely following the masses acting as a tail to a movement, but develops a relationship which is perpetually interconnected. Stalin was later to state that the party was the “general staff” of the working class, and that one without the other simply does not work.

But what of the charge, frequently made by Lenin’s critics from anarchists to fascists and every shade in between, that the Leninist concept of the party is nothing more than a dictatorship of middle-class radicals over the working class? Or the related charge that the “professional revolutionaries” that Lenin was advocating for the training of all be middle-class radicals?

Lenin answered this point directly within the pages of What Is To Be Done?:

“Our very first and most pressing duty is to help to train working-class revolutionaries who will he on the same level in regard to party activity as the revolutionaries from amongst the intellectuals (we emphasise the words ‘in regard to party activity’, for, although necessary, it is neither so easy nor so pressingly necessary to bring the workers up to the level of intellectuals in other respects).

“Attention, therefore, must be devoted principally to raising the workers to the level of revolutionaries; it is not at all our task to descend to the level of the ‘working masses’ as the Economists wish to do, or to the level of the ‘average worker’.” (Chapter 4)

Lenin was very clear on the priority for the training and development of workers who could be “on the same level” with regard to party activity as the communists who came from the middle-class intelligentsia. His later comment in the above quote regarding bringing workers up to the same level as intellectuals in every respect being less pressing should be understood as political education regarding the party and its role being the most important concern.

Lenin envisioned the party needing to raise the level of political education of worker-communists in order that they can participate within the party on the same level as the intellectuals. He understood very well how fatal it would be for a party just to consist of intellectuals who remained alien to the working class.

What Is To Be Done? remains Lenin’s foundational text. It is upon his theory (and later practice) of party organisation that we find expressed his thoroughgoing practice of the Marxist method. His understanding of the limitations of the trade union struggle and the powerful nature of bourgeois ideology within the working class has been proven correct in many struggles across the world, often with tragic consequences in those countries where no Leninist party actually existed to lead the struggle in a revolutionary direction.

What Is To Be Done?, particularly the analysis on class-consciousness, education and the role of the party is misrepresented by reactionaries precisely because of the powerful truths that it contains.

On the 99th anniversary of his death, the most fitting tribute we can pay to Comrade Lenin is to read and understand this foundational work.